Lughnasa Harvest Moon

Second draft of my essay for ModPo (Modern and Contemporary Poetry) finished. It’s  here and shows what close reading (at least my still learning version) is. The poem is by Emily Dickinson.

here and shows what close reading (at least my still learning version) is. The poem is by Emily Dickinson.

I taste a liquor never brewed —

From Tankards scooped in Pearl —

Not all the Vats upon the Rhine

Yield such an Alcohol!

Inebriate of Air — am I —

And Debauchee of Dew —

Reeling — thro endless summer days —

From inns of Molten Blue —

When “Landlords” turn the drunken Bee

Out of the Foxglove’s door —

When Butterflies — renounce their “drams”

I shall but drink the more!

Till Seraphs swing their snowy Hats —

And Saints — to windows run —

To see the little Tippler

Leaning against the — Sun —

In your short essay, do a close reading of this poem. Use as a model the close readings done in the several filmed discussions of other poems by Dickinson.

You may, for example, discuss at least briefly every line of the poem. Or you may choose what you consider to be key lines (or metaphors or terms) and explain each of them fully.

Your essay will be evaluated according to how well you addresses the poem’s form, its use of (shifting) metaphor, and the extent to which its meaning is open. You should try to explain the story Dickinson tells here. For instance, you might say what happens to the speaker as the result of her inebriation? What does this have to do with the way the poem is written?

My answer (so far, I have more work to do on the question of form and how the poem’s story relates to its form.)

The poem explores a connoisseur’s palate for the ecstatic, probably the ecstasy of creation. She (Dickinson? Another I?) tastes this ecstasy as a liquor, not one found in package stores, but a liquor never brewed. She drinks it from a beer hall stein that has been filled not with liquid but with pearl or pearls, indicating, I suppose, that it’s used for finery stuff than Alcohol. Dickinson refers to wineries on the Germany river, the Rhine. This is the chief wine producing area of Germany now and was in the mid-nineteenth century, too. Even the famous Rhenish wine makers could not produce a liquor as fine as the poet drinks.

She (Dickinson? Another I?) tastes this ecstasy as a liquor, not one found in package stores, but a liquor never brewed. She drinks it from a beer hall stein that has been filled not with liquid but with pearl or pearls, indicating, I suppose, that it’s used for finery stuff than Alcohol. Dickinson refers to wineries on the Germany river, the Rhine. This is the chief wine producing area of Germany now and was in the mid-nineteenth century, too. Even the famous Rhenish wine makers could not produce a liquor as fine as the poet drinks.

She gets inebriated from breathing alone, an “Inebriate of Air.” It’s easy to imagine here in stanza 2 an early morning walk, breathing in the cooled air of the night and getting wet from the dew; perhaps she picks her feet up and begins a dance, a reeling. This dance becomes an ecstatic one, perhaps like the whirling Dervishes, that continues “thro endless summer days”.

The fourth line of stanza 2 seems to me to read with the first line of stanza 3. The endless summer days—inns of Molten Blue (the gambreled sky of “Tell all the Truth but tell it Slant”?)—have guests. “Landlords” remove the drunken (ecstatic) bee from the Foxglove, could be the flower, could be the name of a pub or bar or inn. The Butterflies give up, renounce, their drams, their tots of liquor. Renouncing is a temperance flavored term or a religious one related to repentance. The Butterfly gives up their nectar willingly while the drunken Bee gets ejected.

Neither ejection or renunciation works for the poet. Dickinson resolves to keep right on drinking. This reminds me of the Sufi poets for whom inebriation and intoxication were euphemisms for religious ecstasy though; I think the poet has a similar, but secular meaning in mind.

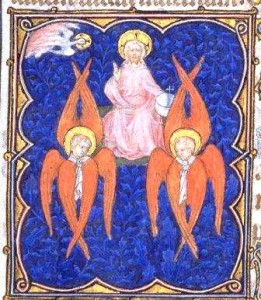

The abstract and pantheistic ecstasy of the first three stanzas however, seems to curve  acutely toward the explicitly religious when we come to Seraphs and Saints in the fourth. Seraphs were fiery angels, the burning ones, who flew round and round the celestial throne singing holy, holy, holy. Saints, in the context of New England circa nineteenth century probably referred to church goers, not Catholic saints, but church goers still. Both the burning ones and the ordinary Saints of the church stop their explicitly religious activity, the Seraphs “swinging their snow Hats” and the Saints to (church?) windows run. Drawn by voyeurism toward a pagan ecstasy, they see the poet, the little Tippler, the inebriate of air and debauchee of dew, leaning.

acutely toward the explicitly religious when we come to Seraphs and Saints in the fourth. Seraphs were fiery angels, the burning ones, who flew round and round the celestial throne singing holy, holy, holy. Saints, in the context of New England circa nineteenth century probably referred to church goers, not Catholic saints, but church goers still. Both the burning ones and the ordinary Saints of the church stop their explicitly religious activity, the Seraphs “swinging their snow Hats” and the Saints to (church?) windows run. Drawn by voyeurism toward a pagan ecstasy, they see the poet, the little Tippler, the inebriate of air and debauchee of dew, leaning.

Ah. Does she lean on the everlasting arms of Jesus or in the strong arms of the Father? No. We’ve never really left the abstract and pantheistic ecstasy of stanzas one through 3. No, she leans against the Sun, the burning one that exists within this realm and a metaphor for her creative ecstasy.