Beltane Rushing Waters Moon

“Everyone sees the unseen in proportion to the clarity of his heart, and that depends on how much he has polished it. Whoever has polished more, sees more, unseen forms become manifest to him.” -Jalal ad-Din Rumi

Bonnie, a rabbi in training and a former high level bureaucrat for the U.S. National Forest Service based in D.C., led our mussar class yesterday. Mussar is an odd (to me) blend of ethics and spirituality, a way of living the 613 mitzvot, or laws, found in the Torah. Since the laws themselves have the unified purpose of leading the faithful on a sacred journey that carries them closer and closer to God, mussar (ethics in Hebrew) is technically an ethical system with a spiritual aim, one embedded in the unique cultural experience of Jewish history.

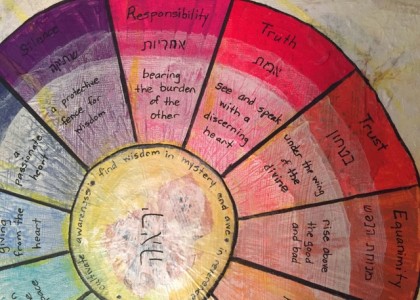

Mussar intends to guide this sacred journey through measurable development of character traits, or middah. The measurability comes in as mussar students, like Kate and me, learn a particular middah, then decide on incremental steps we can take to increase its presence in our lives. We record our progress in a journal and reinforce it through the use of focus phrases. Well, that’s the theory anyhow. It’s taken me nearly a year to get my intellectual footing, so I’ve focused on learning about learning mussar rather than using those tools. I do see their value.

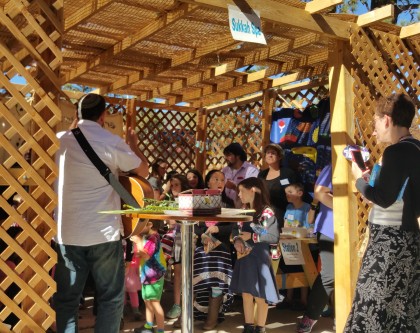

An intriguing pagan element runs throughout the Judaism I’ve been exposed to at Beth Evergreen. The Jewish liturgical year is on a lunar calendar. Shabbat begins at sundown on Friday and Friday shabbat services are held at night. Sukkot is a harvest festival, held outdoors in a sukkot booth. Tu BiShvat is new year for the trees. Judaism is also very body positive, actively opposing ascetic practices that exist in some forms of Christian monasticism, and encouraging the enjoyment of sex.

An intriguing pagan element runs throughout the Judaism I’ve been exposed to at Beth Evergreen. The Jewish liturgical year is on a lunar calendar. Shabbat begins at sundown on Friday and Friday shabbat services are held at night. Sukkot is a harvest festival, held outdoors in a sukkot booth. Tu BiShvat is new year for the trees. Judaism is also very body positive, actively opposing ascetic practices that exist in some forms of Christian monasticism, and encouraging the enjoyment of sex.

Bonnie highlighted that element yesterday in her mussar lesson on the middah of clarity, clarity of self and soul. Tahara is the Hebrew word for clarity. Her examples for achieving and practicing clarity focused on the medieval four elements: earth, air, wind and fire.

Water – Bonnie offered a quote from the novelist Julian Barnes: “Mystification is easy; clarity is the hardest thing of all.”

Water – Bonnie offered a quote from the novelist Julian Barnes: “Mystification is easy; clarity is the hardest thing of all.”

She then described still water, with the sediment settled out, as an instance of crystal clarity. Bonnie suggested three examples of how water facilitates clarity in Jewish ritual life: the mikveh, tevilah and netilat yadayim. The mikveh and the tevilah are ritual immersion in water, the first in a bath, the second in running water. Netilat yadayim is handwashing after contact with a corpse, burial or visiting a cemetery. The water carries away any tumah, spiritual impurity.

Finally, she gave ways of embodying this mussar practice:

Swim, float, dangle your bare feet in water. Take a dip in a bubble bath or a hot spring. Stay out in the rain, don’t run for cover, splash. Get out/in/near open water.

Interestingly, in Judaism the soul is pure. As the Psalmist says: The soul that you, my God, has given me, is pure. You created it, you formed it, you breathed it into me. No original sin here. The water rituals wash away shmutz, a film or a build up, spiritual impurity, that clouds the pure soul. Result: clarity.

Thinking of clarity, a clearly seen pure soul, in this way helps any encounter with water, air, earth or fire act as a spiritual practice, reminding us of the need for clarity while helping us scrape off the shmutz.

This marriage of the elemental and the spiritual resonates for me. I once referred to gardening as a tactile spirituality. These ideas expand that notion in a helpful way. The reimagining faith project intersects with this approach to mussar.