Samain, 2013

Fall Samhain Moon

Tonight is Samhain, also known as All Hallow’s Eve, and Halloween. An abbreviated thick description (see post below for thick description) for this Samhain, in this place, 3122 153rd Ave N.W., Andover, Minnesota could begin with any aspect gathered in to this day and its night, but we’ll begin with the firepit.

description (see post below for thick description) for this Samhain, in this place, 3122 153rd Ave N.W., Andover, Minnesota could begin with any aspect gathered in to this day and its night, but we’ll begin with the firepit.

Kate and I hired Javier Celis to finish a firepit begun several years before by me, worked on by brother Mark two years, but needing some finishing work. Javier and his crew made the granite paving stones, from a cobbled street in Minneapolis, into a neat circle, lined the firepit with ground stone and put crushed marble around the outside of it. They also laid down landscape cloth and thick mulch over the entire area, a former compost pile.

Kate’s family had a firepit in their home in Nevada, Iowa and we both enjoyed them at other’s homes. The firepit hearkens back to campfires of native americans and pioneers here in the U.S. They gave warmth, light and provided heat for cooking.

The fire itself pushes back further to a fundamental separation between hominids and  their close primate relatives, the domestication of fire. Who knows how it happened? Embers from a lightning struck tree conserved overnight by accident? A fire on the veldt which left grasses aflame and led to their use as early kindling? This basic transition, an elemental moment, as essential to our future as a container for water, lives on in our fascination with fireplaces and bonfires.

their close primate relatives, the domestication of fire. Who knows how it happened? Embers from a lightning struck tree conserved overnight by accident? A fire on the veldt which left grasses aflame and led to their use as early kindling? This basic transition, an elemental moment, as essential to our future as a container for water, lives on in our fascination with fireplaces and bonfires.

Bonfires, especially, may be linked, probably are linked, to the fear of night stalking predators, meat eaters for whom human meant food. So we feel safe around a bonfire, huddled around it, just a bit of the thrill left over when that thrill came from the very real possibility of death by fang or claw.

In the Celtic tradition, which we celebrate tonight, the bonfire had sympathetic magic at  its core. In the spring, on Beltane, the fire transferred its vital energy to the soil where it could quicken the seed and ensure a successful planting. The opposite end of the year, Summer’s End, or Samhain, finds the bonfire a way of ensuring our warmth and protection from the cold and hungry months ahead.

its core. In the spring, on Beltane, the fire transferred its vital energy to the soil where it could quicken the seed and ensure a successful planting. The opposite end of the year, Summer’s End, or Samhain, finds the bonfire a way of ensuring our warmth and protection from the cold and hungry months ahead.

My Celtic roots run through Ireland, the Correls, and through north Wales, the Ellises, and, perhaps, through County Kent, the Keatons. The Correls came as potato famine immigrants in the late 19th century and we have no information about the Keaton immigration though it might have been in the same era. The Ellises we know came here first in 1707 when Richard Ellis was put ashore by a greedy sea captain, sold as an indentured servant to pay his fare. His mother had paid his fare in Dublin, Ireland where her husband, a captain in William and Mary’s occupying army, had recently died.

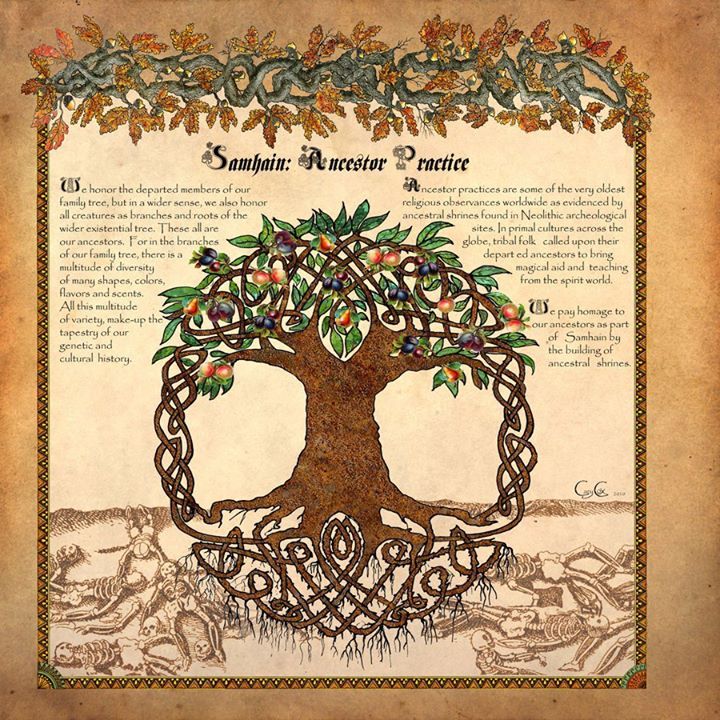

Searching in my own and the more general Celtic past led me to the Great Wheel of the  Year. It has gradually become a center point for reimagining my faith, helping me find the rhythms of the year and of human life as key sacred moments. Thus it is, at least in part, that we go to our firepit this year, to build a bonfire and say the names of our ancestors, standing there around the universal symbol of human protection, warming our hands and waiting as the Great Wheel turns from the bounty of the growing season to the Great Rest of the fallow time.

Year. It has gradually become a center point for reimagining my faith, helping me find the rhythms of the year and of human life as key sacred moments. Thus it is, at least in part, that we go to our firepit this year, to build a bonfire and say the names of our ancestors, standing there around the universal symbol of human protection, warming our hands and waiting as the Great Wheel turns from the bounty of the growing season to the Great Rest of the fallow time.

uogmt4