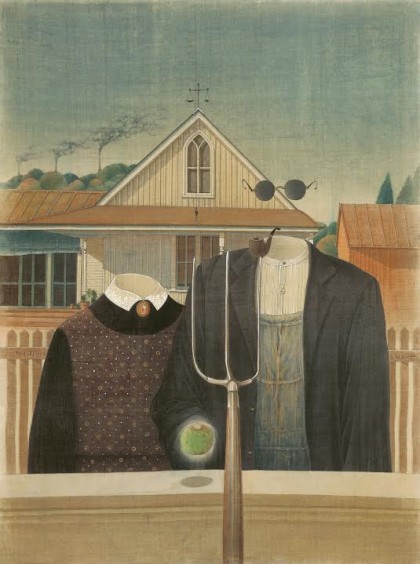

In these pages I plan to post theoretical work I’m doing about art, art criticism, ekphrasis and whatever else seems germane to my pilgrimage along the ancient trail of art. This latest phase of my journey comes after resigning from the Minneapolis Institute of Art following 12 years of volunteering, 7 as a docent.

Mabon Elk Rut Moon

Inertia. Strong. It was true in Minnesota and true here. Hard to get the body up and out of the house, into the city or over to a trail or to an interesting locale, even one reasonably nearby. If inertia comes down on the object in place side too much, especially as we age, we become, by our own choice, homebound.

Inertia. Strong. It was true in Minnesota and true here. Hard to get the body up and out of the house, into the city or over to a trail or to an interesting locale, even one reasonably nearby. If inertia comes down on the object in place side too much, especially as we age, we become, by our own choice, homebound.

Didn’t listen today. Got in the truck and drove into Denver to the Denver Art Museum and the Metropolitan University of Denver’s Visual Arts Center. Got lost a little so I found parts of Denver I hadn’t seen. A good thing.

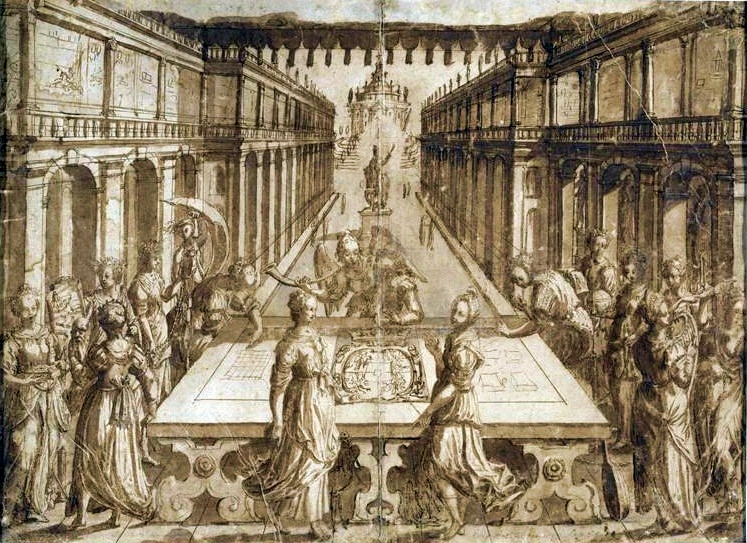

The occasion today was a DAM initiated show about Castiglione, a 17th century Italian painter who, like Caravaggio, seemed as much psychopath as artist. A DAM curator feels Castiglione has been unfairly ignored and mounted this exhibition to try a 21st century restoration of his reputation. After looking at the show carefully, it is my opinion that history has treated Castiglione fairly. His work doesn’t have, to my eye, that extra pop that a Durër or a Lotto or a Caravaggio brings to painting and drawing.

He’s interesting. His work shows definite skill and imagination, but I didn’t feel moved to look and relook. I do not feel, for example, that I need to go see the show a second time. That might change. This is a first impression. Too, the show was hung in an unusually obtuse way in terms of flow, color and positioning of the works. It was confusing to follow, the rooms often too bare and the colors of the walls not a good choice for seeing the works well.

I bought the catalog and plan to read it. Challenge my own opinion. I was excited to see this show because I like discovering a new artist, their work. I like that the curator too the risk and that he’s done so much scholarly work on Castiglione. Learning about Castiglione will advance my own understanding of art history, of that time period in Italian art and in the way curators/art historians evaluate and reevaluate artists, so it’s far from a waste.

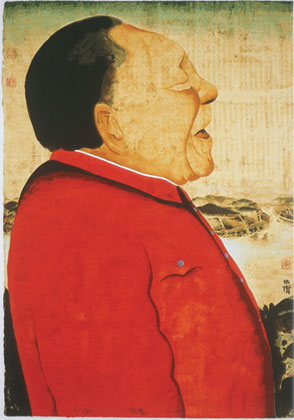

Jon, step-son and art teacher, recommended another exhibit I would never have seen within his drawing my attention to it. This is a show of contemporary gongbi painting at the Metropolitan University of Denver’s Visual Arts on Santa Fe in the heart of the city’s art district. Gongbi is a difficult to master painting technique with roots in the Han dynasty. It emphasizes the slow build up of form and color, utilizing a very tricky two brush in one hand painting method that looks almost impossible to learn.

In this show a handful of contemporary Chinese artists carry this ancient school of art into the contemporary world of irony and surrealism. The result is wonderful. I liked it so much that I asked to see the price list for the paintings on the off chance that the market for them might not have been made yet. Faint hope. The cheapest was $2,500 with most in the $20,000 range.

Living artistic traditions being united with contemporary sensibilities is fascinating. In this exhibition a style used to do jewel like representations of flowers, birds and insects has been used to create cheeky commentary on China’s tradition as it interacts with the west. Worth seeing if you get the chance.

JMW Turner 8/27/2015

Lughnasa Labor Day Moon

Stefan Helgeson sent out a Turner watercolor and asked, what does it say to you? How does it make you feel? I couldn’t find the watercolor Stefan copied though it bears close resemblance to a series of small works recorded in Turner’s Channel Sketchbook.

Turner was the true artist before his time. He looked closely, especially at the sea and the sky, and attempted to evoke them with minimalist figural representation. Instead he waved at the literal scene by splashing colors together, here a horizon line faintly evident, there a cloud suggested, reflecting on them both perhaps a setting or rising sun. The watercolors of the Channel Sketchbooks seem abstract, related more to Rothko and the color field artists of the mid-20th century than to his late 18th century, early 19th century peers.

Seen in the context of the Channel Sketchbook the piece Stefan chose looks like a short musical piece: a lyrical quiet first movement, read from the bottom up, then a dark moody second, adagio, followed by a third filled with quick 16ths, 32nds flaring then quieting down into the song-like spacing of the first only to rise sharper faster until it fades.

Turner’s work of this sort is brave, putting out there what he sees in his heart, yet, too, still tied to what he sees with his eyes. It’s hard to imagine how much a member of the British Royal Academy, accepted at the age of 15, could be an outlier in this stodgy institution, but Turner was just that.

He was called in his time “the painter of light.” Compare his work to that other artist, Thomas Kinkade, who called himself the painter of life.

Turner saw and dared to paint what he saw and felt. When I look at the work Stefan sent out, I feel challenged to see as Turner saw, to let the little represent the big, to distill the world into its colors and feelings. I feel opened up, spacious, wider somehow and linked by heart to the world around me.

Out of It?

Posted on April 10, 2014 by Charles

Spring Bee Hiving Moon

I spent three hours at the Walker today visiting an exhibition, a large one, on Edward Hopper’s creative process and an exhibition by Jim Hodges: Give More Than You Take. On the way home I began thinking about this question: did I get anything out of it? I certainly enjoyed myself, had a nice lunch at Gather overlooking Hennepin Avenue, the Basilica, the Episcopal Cathedral, Loring Park and Armajani bridge.

But what is the personal value of standing in gallery after gallery, visiting with art in person? There are certainly some answers: participating in a dialogue between artist and viewer that stretches at least as far back as the Chauvet Caves, over 30,000 to 32,000 years old. Learning how the world looks inside another if you accept (and I do) that art turns the inside view outside.

viewer that stretches at least as far back as the Chauvet Caves, over 30,000 to 32,000 years old. Learning how the world looks inside another if you accept (and I do) that art turns the inside view outside.

In the Jim Hodge show I saw many possibilities for textile art that had not occurred to me before and I brought pictures home for Kate, my resident textile artist. This is a quilt like work, quite large, maybe 20 feet across and 8 or 9 feet tall.

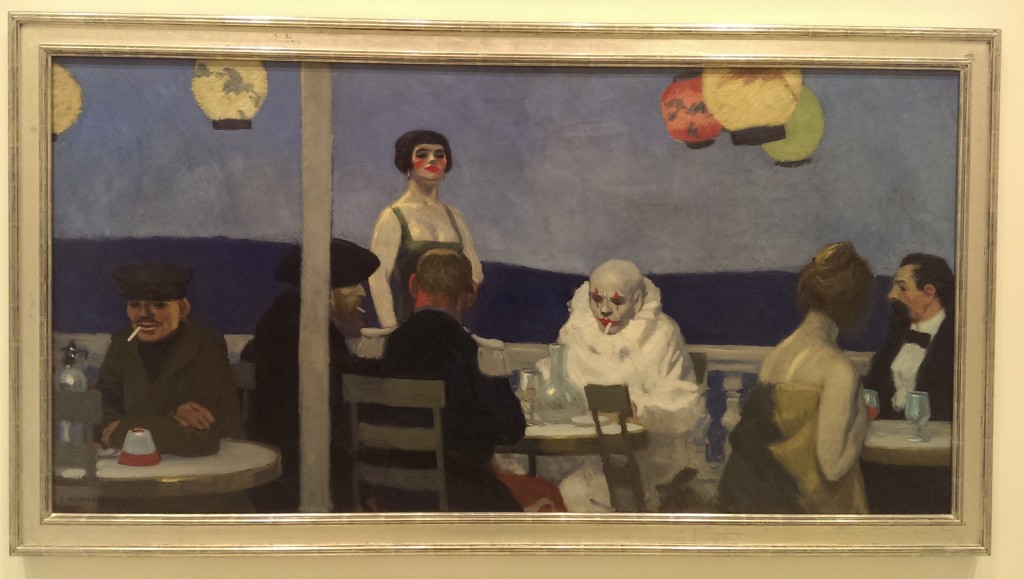

In the case of Hopper, a personal favorite, there was at least a double benefit. The many drawings, often matched with the paintings for which they were preparation, gave a glimpse into Hopper as he worked out his vision. How artists choose to include or eliminate items is very interesting to me. Second, there are a number of paintings sprinkled throughout the show, one from quite early in Hopper’s career, and they, too, show a progression of his overall vision. This one, for example, from 1882 during one of Hopper’s visits to Paris.

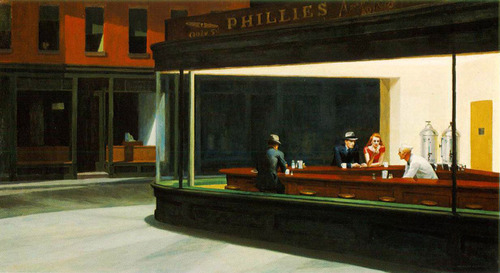

It’s quite a distance from this expressionist work influenced by Lautrec and Degas to this one, Gas, painted in 1940 and much more typical of his later work, post his coming to fame in his 40′s in 1924.

What do I get out of it? Let me probe a little deeper. All those answers above are true, as far as they go, but they don’t get quite as far down as I want to go.

What do I get out of it? Let me probe a little deeper. All those answers above are true, as far as they go, but they don’t get quite as far down as I want to go.

Going deeper gets to the reasons Hopper is a favorite of mine. And, interestingly, I can link these two very different works to explain why he attracts me so much. Let me add a third before I do that, one in the collection of the Walker, Office at Night.

The latter two, Gas and Office at Night, share a use of light that seems to illuminate a realistic scene, but when examined more closely, lights a vaguely representational setting: a gas station, probably a Mobil station but the sign is just too indistinct to read; while the man and woman in Office at Night at first seem to be real individuals, but on closer examination their features are more elemental, more stereotypical, revealing two types of person rather than two individuals in particular.

The light bathes the gas pumps and the night-time office in a manner creating distance between us and the setting. The man at the gas pump is outside the seemingly cheerful light coming from inside the station, not quite reaching where he stands alone. In Office at Night the two workers-we wonder what’s so important that they are there at night-are inside, working, while the light comes from outside where others are enjoying time off from labor.

We don’t see that use of light in the 1882 painting, a use I consider distinctive of Hopper’s later style, but we do see a commonality with the other two, one that gets to my affection for Hopper’s works. Though there are people in each of these paintings, none of them seem to know anyone else is there. Each person’s gaze goes past the person they’re with, or, in the case of Gas, stares at something on the pump, rather than back inside to the station.

To my eye Hopper paints the existential dilemma we all face, one especially acute in the busy city, but also true in the countryside of Gas. That is, we are in this world alone. We live our lives in the presence of other people, yes, but we can never experience the deep Selfness of the other, nor can they experience ours. The light in Hopper’s paintings, again to me, rather than illuminating the settings, highlights this isolation, making it apparent even when the world is well lit. His light has a haunting quality, one that takes me into a revery about the nature of human being.

So. Yes, I guess you can say that I got something out of my trip to the Walker. So much so in fact, that I’ll go back. Soon.

Posted in Art and Culture | Leave a comment | Edit

Art Day

Posted on April 10, 2014 by Charles

Spring Bee Hiving Moon

An art day. One of my struggles over the last year since leaving the MIA has been how to include art in my life with as much frequency and power as the docent program offered, without its limitations and time constraints. I’ve not done well on this.

include art in my life with as much frequency and power as the docent program offered, without its limitations and time constraints. I’ve not done well on this.

At the Journal workshop I committed myself to using the teaching company courses I have on art (4) and taking the Warhol class that begins later this month. (a MOOC) A while back I decided to devote the second thursday as a museum day. My work in Tucson challenged me to consider more, two days a month, or even an art week, devoting one week a month to art: learning, reading, visiting museums and galleries.

[Alexander Young Jackson, Winter, Quebec, (1926)]

Since coming back I have begun using the teaching company courses, interestingly assisted by the habits I learned while taking the MOOC’s I’ve already finished. That is, I watch the videos on my computer, open up Notes and take notes as I listen to the lecture. Reading books and monographs naturally accompanies this effort.

Even so, there is no substitute for seeing work in person. The texture, the light, the display in a museum, gallery, or public place make a large difference in understanding the work. So, today at 10:30 am, I’m going into the Walker to see the new Hopper exhibition. This one focuses on his artistic process through examination of prints. While there, I’ll see a couple of other shows, too.

display in a museum, gallery, or public place make a large difference in understanding the work. So, today at 10:30 am, I’m going into the Walker to see the new Hopper exhibition. This one focuses on his artistic process through examination of prints. While there, I’ll see a couple of other shows, too.

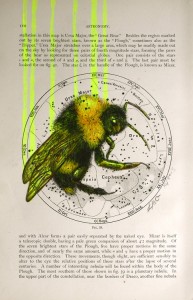

[‘Alchemist’, pencil and acrylic on 1903 Astronomy Map (2013) by Louise McNaught]

I hope in this way to deepen my engagement with art, continue the considerable progress I made over 12 years at the MIA in appreciating and learning from the long tradition of art making.

Spring Bee Hiving Moon

Back from the Guthrie and the Penumbra presentation of Mountaintop, a play focused on Martin Luther King’s last night alive in the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. As it neared the end, it picked up emotional punch using a clever device that I won’t reveal. The pathos of a man about to die because he stood up for love, for justice, can sound wooden on the page, but to see a real man struggling with acceptance, to hear a real woman empathize with him, that’s different. That’s the power of theatre.

There’s a good metaphor used in it, one you may have heard before, but which was new to me. The civil rights movement, the movement for the poor is not a sprint, but a relay race, with one generation handing on the baton to the next.

When we discussed this play briefly at Christos on Monday, I made the observation that  when our generation dies out, the generation who experienced King, Malcom and that whole era will die out, too. That means these characters will pass into history, become captive to interpretation and canonization. A certain amount of that has happened already.

when our generation dies out, the generation who experienced King, Malcom and that whole era will die out, too. That means these characters will pass into history, become captive to interpretation and canonization. A certain amount of that has happened already.

That will be a shame because those years, the 60’s and early 70’s, were so alive and vital. The air crackled with change, with big questions, with thoughts of matters far beyond the vocational worth of a college diploma. And we lived it. It is our direct heritage and I like very much the notion of the baton.

I’m in that part of the race now where the baton is stretched out ahead of me, ready to lay in the hands of another, but my race is not yet run. I’m accelerating, to keep the team ahead.

Honorary Docent Lost

Posted on August 30, 2013 by Charles

Lughnasa Honey Moon

Back in the MIA yesterday morning before my lunch with Tom. Wandering around,  absorbing the images and the galleries, felt good–but unfocused, I was unclear as to my purpose for being there.

absorbing the images and the galleries, felt good–but unfocused, I was unclear as to my purpose for being there.

(5th century painting, Poet on a Mountain Top by Shen Zhou. not in MIA collection)

A long segment of a Chinese scroll, a landscape of black and white mountains, exhibited in a narrow corridor beside the Wu reception hall, sent me into a wistful, calm place and a sudden realization why I like Asian art, especially Chinese and Japanese. Much of it is soothing, contemplative.

As these thoughts and feelings slowly tumbled down the stream of my experience, I came to an explanation of this “spilt ink” and discovered the scroll had been done by a literati artist waiting for his son at a mountain monastery. His son was overdue and he felt, he said, “Lonely and sad.”

The exhibition, “Sacred”, has pieces scattered around the atrium on the second floor,  some mostly installed, others not. It focuses on surfaces, as an art exhibition must: clothing, dance, fluids, walking. This is something I’ve learned recently, that the modern was a turn toward keen appreciation of the surface of things, logical since philosophy from Kant on down has hammered away at our inability to see the thing in itself, the real behind our perceptions, leaving us with what our senses bring to us, the surface of things.

some mostly installed, others not. It focuses on surfaces, as an art exhibition must: clothing, dance, fluids, walking. This is something I’ve learned recently, that the modern was a turn toward keen appreciation of the surface of things, logical since philosophy from Kant on down has hammered away at our inability to see the thing in itself, the real behind our perceptions, leaving us with what our senses bring to us, the surface of things.

Modern science, Darwin being a keen example, constructs its wonders on observation and recognizes that it cannot explain what it cannot apprehend. Yes, there is lots of inference, electron fields, quantum action at a distance, the brain/mind link, but about these things we recognize only what we can measure about them, that is, apprehend. There is no other tool.

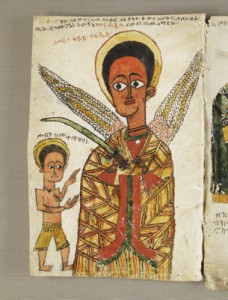

So, yes, I understand the “Sacred” exhibition’s focus on the surface of things, but it will not, cannot touch what causes a man to wear a chasuble or a yarmulke. It will not show the Shiva who dances in the heart of the faithful Hindu or the Buddha mind of the adherent inspired by the Thai walking Buddha. It will, in this regard, I think, fall several measures short of its mark. Too facile, too straight forward. A nice try but not bent enough to capture the mysterium tremendum, the awe that comes with the experience of the holy.

What Sort of Man Was Fragonard?

Posted on September 25, 2013 by Charles

Fall Harvest Moon

By taking the two moocs focused on modernism I’m trying to increase my grasp of a conceptual field: enlightenment-neoclassicism-romanticism-modernism-(post-modernism: in parenthesis because in my mind the existence of post-modernism is still in doubt). The poetry class has done a great job of revealing the tensions and struggles that poets felt as the world lurched from the end of the 19th century through the fertile period around the turn of the century and on through the Great War. It’s heightened my awareness of the moderns experience of fragmentation, the built, the machine driven, the phenomenal as all there is, the quandary between art as it has been and art as it must now be.

conceptual field: enlightenment-neoclassicism-romanticism-modernism-(post-modernism: in parenthesis because in my mind the existence of post-modernism is still in doubt). The poetry class has done a great job of revealing the tensions and struggles that poets felt as the world lurched from the end of the 19th century through the fertile period around the turn of the century and on through the Great War. It’s heightened my awareness of the moderns experience of fragmentation, the built, the machine driven, the phenomenal as all there is, the quandary between art as it has been and art as it must now be.

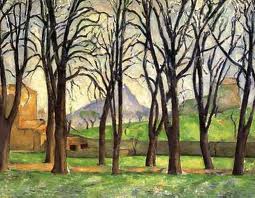

(Cezanne Chestnut Trees at Jas de Bouffan, MIA)

The history of ideas approach of the Modern and Post-Modern has reminded me of modernism’s roots in enlightenment thinkers like Kant, Rousseau, John Lock, Jeremy Bentham and has helped me see how the realist strain in literature, examples being Madam Bovary and especially Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, reflect a similar struggle among novelists.

The rise of science in its current form also begins in the early modern period and I’ll have to wait for another course or book to increase my knowledge there.

to wait for another course or book to increase my knowledge there.

(Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, 1912)

Both courses have helped me understand the trajectory of painting from impressionism, post-impression, fauvism, expressionism, cubism to abstraction and beyond. Painters tried to make painting obvious in paintings in the same way that poets tried to make the creation of poetry obvious in the poem itself. In this sense modern art has a meta-artistic overlay in which the painting reveals its two-dimensionality and its painterly conceits just as modern poetry highlights itself as written, pointing a finger through the subject matter and form back to the poem itself.

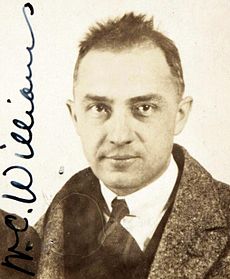

Here is a William Carlos Williams poem in which the writer struggles out loud with the idea of portraiture, one voice trying for the traditional portrait, the other voice disparaging the effort and its apparent lack of success.

idea of portraiture, one voice trying for the traditional portrait, the other voice disparaging the effort and its apparent lack of success.

William Carlos Williams, “Portrait of a Lady” (first published in the Dial, August 1920)

Your thighs are appletrees

whose blossoms touch the sky.

Which sky? The sky

where Watteau hung a lady’s

slipper. Your knees

are a southern breeze — or

a gust of snow. Agh! what

sort of man was Fragonard?

– As if that answered

anything. — Ah, yes. Below

the knees, since the tune

drops that way, it is

one of those white summer days,

the tall grass of your ankles

flickers upon the shore –

Which shore? –

the sand clings to my lips –

Which shore?

Agh, petals maybe. How

should I know?

Which shore? Which shore?

– the petals from some hidden

appletree — Which shore?

I said petals from an appletree.

From Emptiness to Emptiness

Posted on September 28, 2013 by Charles

Fall Harvest Moon

This scroll painting reads from right to left (here top to bottom). I could not find images of equivalent sizes. Why I wanted to show this, one of this week’s objects on 82nd and Fifth, is its rendering of a Daoist perspective on life.

It begins with the temple barely visible at the far right, a vantage point from which the rest of the landscape can be seen. As the eye moves along the landscape (a life passing), it comes finally to the end where the mountains disappear into mist, emptiness. We come from emptiness and we return to it. We have the time in between shown on this scroll.

Some art historical material from the Met’s website is below.

“The Daoist adept Fang Congyi (ca. 1301–after 1378) was active in the Upper Purity Temple at Mount Longhu (Dragon Tiger Mountain), Jiangxi Province, the center of the Zhengyi (Orthodox Unity) order. His mystical Cloudy Mountains diverges from the more restrained style of most Yuan literati, transforming a mountain range into a writhing dragon vein of energy that uncoils out of the distance only to vanish into a misty void. The Longhu area was described by Fang’s contemporary Song Lian (1310–1381) as the capital of the immortals. The desire to find one’s destiny in this realm was the driving force behind Daoist thought and art.”

“Fang Congyi…imbued with Daoist mysticism, … painted landscapes that “turned the shapeless into shapes and returned things that have shapes to the shapeless.””

“According to Daoist geomantic beliefs, a powerful life energy pulsates through mountain ranges and watercourses in patterns known as longmo (dragon veins). In Cloudy Mountains, the painter’s kinetic brushwork, wound up as if in a whirlwind, charges the mountains with an expressive liveliness that defies their physical structure. The great mountain range, weightless and dematerialized, resembles a dragon ascending into the clouds.”

Metropolitan Museum Website

Does Great Literature Make Us Better?

Posted on June 6, 2013 by Charles

Beltane Early Growth Moon

Does Great Literature Make Us Better? NYT article you can find here.

I’ve read great literature off and on my whole life, starting probably with War and Peace as a sophomore or so in high school. I’ve also read a lot of not great, but not bad either literature and have even written some myself. And, yes, I’ve read some distinctly bad literature, but not on purpose.

a sophomore or so in high school. I’ve also read a lot of not great, but not bad either literature and have even written some myself. And, yes, I’ve read some distinctly bad literature, but not on purpose.

A formative experience in my reading life occurred in my sophomore year of college when I took a required English literature class. Before taking the class I had given serious thought to majoring in English. Then I had whatever his name was for a professor. He told me what the books I read in his class meant. He also claimed, proudly, to read Time Magazine from cover to cover each week as a form of discipline. (That would have been discipline for me, too. Punishment.)

Whether he represented English literature professors or not I don’t know, and I suspect now that he probably didn’t, but at the time I decided I could do the work of an English major without putting up with anymore of that kind of instruction. I would read. And I did and I have.

now that he probably didn’t, but at the time I decided I could do the work of an English major without putting up with anymore of that kind of instruction. I would read. And I did and I have.

(Greuter Seven liberal arts 1605)

[That’s how I ended up in Anthropology and Philosophy for a double major. Though I did have almost enough credits for a geography minor and a theater minor. The theater credits were almost all in the history of theater, which I found fascinating. The geography business came about because I was interested in the Soviet Union and, to a lesser exent then, China.]

Has reading Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Singer, Hesse, Austen, Mann, Kafka and all those others made me a better person? Hell, I don’t know. In the article quoted above I think the writer refers to an argument about liberal arts in general; that is, that studying the liberal arts makes one more able to think critically in a complex world and, therefore, to act with a higher level of moral sensitivity.

made me a better person? Hell, I don’t know. In the article quoted above I think the writer refers to an argument about liberal arts in general; that is, that studying the liberal arts makes one more able to think critically in a complex world and, therefore, to act with a higher level of moral sensitivity.

That the liberal arts and reading great literature teaches critical thinking is, I think, established. They do this by the comparative method, familiar to students of anthropology and philosophy and literature and theology. How does it work? In the words of blue book essay tests since time immemorial, you compare and contrast. By comparing this culture to that one, or this writer to that one, or this book to that one, or this period of philosophy to that one or this theological perspective to that one, a sensitivity to the variations in argumentation, in problem solving, in abstract analysis becomes second nature.

This sensitivity to the variations does not, I think, breed a more moral person, but it does produce a more humble one, a person who, if they’ve paid attention, knows that this solution or that one is not necessarily true or right, but, rather is most likely one among many. This humility does not cancel out conviction or commitment, rather it positions both in the larger reality of human difference.

produce a more humble one, a person who, if they’ve paid attention, knows that this solution or that one is not necessarily true or right, but, rather is most likely one among many. This humility does not cancel out conviction or commitment, rather it positions both in the larger reality of human difference.

So, in the end, I don’t believe the case for reading great literature is to be made in its efficacy or lack of it in creating moral sensitivity, but rather in great literature’s broadening of our horizon and in the concomitant deflation of our sense of moral righteousness, perhaps, oddly, the very opposite of creating a more moral person.

No Longer Part of the Club

Posted on June 6, 2013 by Charles

Beltane Early Growth Moon

Back to the MIA for, believe it or not, my first time since January 20th, the day of my last terra cotta warrior tour. Partly inertia, mostly distancing myself during a time of decision about my future with the museum. I felt strange. No easy parking. No badge. No task. Having to stand in line for a ticket I acquired with my membership card. Plus there was a sense of no longer belonging, as if an invisible protective shield had been stripped away. Which, in a way, it had. No badge means no magnetic access to the hallways and rooms not accessible to the public.

terra cotta warrior tour. Partly inertia, mostly distancing myself during a time of decision about my future with the museum. I felt strange. No easy parking. No badge. No task. Having to stand in line for a ticket I acquired with my membership card. Plus there was a sense of no longer belonging, as if an invisible protective shield had been stripped away. Which, in a way, it had. No badge means no magnetic access to the hallways and rooms not accessible to the public.

(I visited my favorite object in the museum today, this Sung Dynasty tea bowl with a real leaf imprinted in the glaze.)

Now I’m part of the public though I do have a small laminated card that reads Honorary Docent. It fits snugly between my Medicare and AARP cards. One more certification that I’m: OLD.

However. Once there I felt at home and realized instantly that though the resignation was an end, that it is (I know this is a cliche) a beginning, too. It is a beginning in this regard. I have served a 12 year apprenticeship concerning the objects in this museum, in how to conduct art historical research and in how to share that research with the public. There has been, too, education in areas broader than this particular museum and increased self education on matters artistic, historical and cultural relating to the world of art.

an end, that it is (I know this is a cliche) a beginning, too. It is a beginning in this regard. I have served a 12 year apprenticeship concerning the objects in this museum, in how to conduct art historical research and in how to share that research with the public. There has been, too, education in areas broader than this particular museum and increased self education on matters artistic, historical and cultural relating to the world of art.

(this will be a new favorite when it arrives with the Clark collection.)

With that apprenticeship and its wearying (both from a conducting and researching tours perspectives, but also from a driving perspective) and distracting days of touring behind me, I can now concentrate myself on the art that became important to me over that time, in particular the Asian collection, certain periods of European and American painting and the world of contemporary art.

in particular the Asian collection, certain periods of European and American painting and the world of contemporary art.

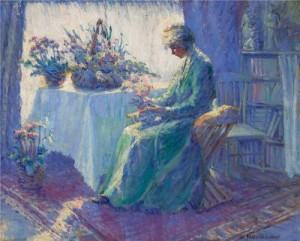

(Harriette Bowdoin – Morning Shadow and Sunlight)

My key focus will remain in the Asian art, but I love the pre-Raphaelites (take that snobby NYT art critic) and the pre-Renaissance and Renaissance works as well as certain other movements like Symbolism, American Realism and the Ashcan School, surrealism. I will need to figure out another way to make my trips into the museum part of a learning program. But I know I can do that. And I’ll still enjoy going in just to wander around, to visit special exhibitions, see friends.

So, here’s a glass to a new relationship with an old partner.

Art in the Age of Truthiness

Posted on June 6, 2013 by Charles

Beltane Early Growth Moon

Saw this show before its final day, June 9th. Saw it late, I’ll admit and practically speaking didn’t allow myself time to revisit it. But I don’t think I would have gone again anyhow. Maybe.

This show focuses on epistemology, how we know what we know, and more specifically on the ways in which elements of contemporary life serve to distort truth, dislodge it, falsify it, cover it up, play with it, even invent it.

cover it up, play with it, even invent it.

It was interesting. Which, I realized today, is my general attitude toward contemporary art. It’s interesting. Shane Carruth, director of Primer and of a recent second film, Upstream Color, talked about his belief that all narrative is veiled at the Walker screening of Upstream Color last month. He could have spoken, I think, for Liz Armstrong, saying maybe, all truth is veiled.

(Seung Woo Back Real World series)

There were the photos of the Oval Office, accurate, except where they weren’t. The boxing gloves made from a Leadbelly lp, male hand bones and other materials. The curious abstract photographs of surveillance satellites, an artist watching the watchers watching us. There were the very well done photographs by Seung Woo Back of a theme park in Seoul that has replicas of Angkor, the Chrysler Building, the Twin Towers, the Brooklyn Bridge. That long truck displayed in the dark, filled with ominous tanks and boxes and cargo containers. The photographs of the installation of eerily human sculptures forcing us to pick out the people from the sculpture. And the frames of famous paintings displayed from the rear. Intellectual and physical sleight of hand.

Brooklyn Bridge. That long truck displayed in the dark, filled with ominous tanks and boxes and cargo containers. The photographs of the installation of eerily human sculptures forcing us to pick out the people from the sculpture. And the frames of famous paintings displayed from the rear. Intellectual and physical sleight of hand.

(Leandro Erlich

Stuck Elevator, 2011)

All interesting. Thought provoking. A critique of much of our current life. All that yes. And much of it very well made, technically compelling. But my heart did not visit this show. My head did. And my head played the mind game of puzzling out what critical nuance had just been displayed. My head nodded at the violation of the compact between fact and conclusion. Yes, I see. I get it. Oh, well done.

But my heart was not there. Just as it is often absent from the work displayed at the Walker. I find much of the work at Walker interesting, too. Challenging my received assumptions. Making my rethink perspectives, yes. Introducing me to new vantage points. Yes. But lacking that complex of aesthetic finesse, concept and overall presentation that goes beyond my critical faculties and touches me emotionally.

Ed Ruscha comes to mind as one who touches me emotionally. Some of Cindy Sherman’s work. Much of the modernist era: colorfield painters like Morris Louis and abstract colorists like Mark Rothko both punch right through my interesting wall and put a finger or two into vulnerable queasy spots. A lot of Warhol does, too. Probably could come up with more if I belabored it, but you get the point.

colorists like Mark Rothko both punch right through my interesting wall and put a finger or two into vulnerable queasy spots. A lot of Warhol does, too. Probably could come up with more if I belabored it, but you get the point.

(Ed Ruscha)

This stuff (the Truthiness show), definitely provocative, certainly critical in a helpful way of our time and our ways of thinking, often well made doesn’t do it. I don’t know if that’s important for everyone when it comes to art, but it is to me. And by that standard this show fails.

Oh, and let me make one other point. None of this is even close to new. The Sophists bent truth and perception in classical Athens. Hinduism sees the whole world as Maya, illusion. Buddhism says it’s our sense perception that entangles us in samsara. Trompe l’oiel painting. Even, if you stop to consider it, perspective and the tradition of so-called realism.

truth and perception in classical Athens. Hinduism sees the whole world as Maya, illusion. Buddhism says it’s our sense perception that entangles us in samsara. Trompe l’oiel painting. Even, if you stop to consider it, perspective and the tradition of so-called realism.

Posted in Art | Leave a comment | Edit

May 10, 2013

These two tables, Interrogation of the Object and Interrogation of the Interpreter, are a barebones beginning. My hope is to create easy to use methods and tools that can deepen and broaden our experience of works of art we want to know better. This work grows from my use of exegetical and hermeneutical techniques applied to ancient literature.

Interrogation of the object

Interrogation of the interpreter

| What do I bring to the work? Existentialism has been my north star since early college. When I come to Hopper’s paintings, the sense of isolation and social distancing existentialism posits comes alive on canvas for me. Thus, to the extent that this does not match Hopper’s intent, this is a bias about which I have to be aware.Nighthawks in particular plays on a sense of the city and, especially, the city at night, late night as the metaphorical equivalent of existentialist thought. It’s bleakness and the geometric convergence on the cash register suggest to me a critique of the city as marketplace and, in fact, as community. In addition, the viewpoint, from outside the diner looking in, suggests a Nighthawk, a predator seeking prey. Hopper himself points toward this interpretation. | ||

| -received interpretation I believe my understanding described above reflects a fairly common interpretation of Nighthawks and of Hopper’s work in general. And, in that sense, of course, Hopper’s intent is of little moment. The question of the relationship between the artist’s intent and a viewer’s interpretation, reaction to a work is a fascinating question that requires more space than available here. | ||

| -history with the work Until I began probing Nighthawks for this project, I knew it only in the way I know American Gothic or Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer. A familiar work, one that fits that overused word, iconic. It crystallizes on canvas a noir experience present in the film noir works featuring Humphrey Bogart, Orson Welles. Such films as Sunset Boulevard, Touch of Evil, the Maltese Falcon. In that sense it seems to locate itself in the late 1930’s, early 1940’s, which is, in fact, when it was made. | ||

| -taste preferences/biases I like Hopper’s clean light, clear lines and spare compositions. The sense of spaciousness and clarity also appeals to me. I would not say I have a realist bias, but I enjoy and appreciate that aspect of Hopper’s work and his continuation of the American realist tradition represented by Copley, Homer and Eakins. | ||

| -interpretive dialectics Here my point is that we come to a work of art predisposed toward some point on different dialectical continuums. The particular dialectics I’ve laid out here are not so important as the realization that our reactions are located within a range of other possible reactions. These are examples. | ||

| Patience-impatience How much time and attention does a given work call out of you? Do you approach it, look, move on or does it make you stop, pause, consider? Can you modify your natural impulse to look a bit longer, think a bit harder, open yourself to feelings evoked rather than imported to the object?With Nighthawks I find myself drawn in, made to pause by the spaciousness and the weary narrative presented. What’s happening? Why does a scene that seems very familiar have such a dark undertone? Is the light just bravery against the night or is it hope for the isolated? | ||

| Openness-rigidity Can I change my understanding? Does Hopper’s statement that the work intends to consider dangers in the night, predators, Nighthawks, alter my existentialist, noir interpretation? Would a focus on the realistic, impressionistic roots of Hopper’s art require a different inflection?I’m not sure how open I am to changing my received interpretation of Nighthawks. The interpretation that seems to come naturally to me helps me locate myself in the American story. I’m not sure I want to give that up. | ||

| Joy-despair When I look at Nighthawks, what are the dominant feelings it evokes? In this case focusing on the joy-despair dialectic. It falls, for me, on the far end of despair.Is there a way of seeing Nighthawks that might move the meter more toward joy? | ||

| Beauty-ugly This is an interesting dialectic here. I would not describe Nighthawks as beautiful in the Raphael or Fra Lippi or Botticelli sense. Perhaps it fits a certain baroque sensibility where the darkness enhances the aesthetic. It’s not ugly, at least to me.The spare, stripped down shapes, the luminosity, the isolation of the figures, the careful composition make it unified and in that unification, pleasing. To me. | ||

| Any other dialectics you can imagine Here you can imagine other dialectics: modern-traditional, realist-abstract, fun-not fun, painterly-not… | ||

| The questions of the object’s interrogation turned onto you. I intend to work more on both lists, pruning and adding until they balance each other, are easy to use, yet significant enough to be worth engaging. At least sometimes. | ||

| The Hermeneutical Circle: The key move, after doing both of these and whatever else might be important for your understanding of a work, is to recognize the interrogation of the work and yourself has changed you and your understanding of the work. | ||