Lughnasa Kate’s Moon

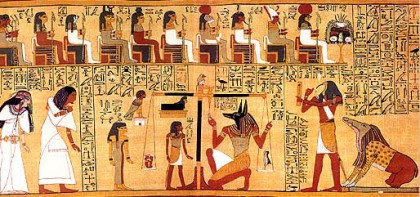

Moving forward, slowly, with Jennie’s Dead. Exploring the religion of the ancient Egyptians, trying to avoid hackneyed themes, not easy with all the mummy movies, Scorpion King, Raiders of the Lost Ark sort of cinema. Jennie’s Dead is not about Egypt, ancient or otherwise, but it plays an important role in the plot. Getting started is difficult, trying to sort out where the story wants to go, whether the main conflict is clear, to me and to the eventual reader.

Moving forward, slowly, with Jennie’s Dead. Exploring the religion of the ancient Egyptians, trying to avoid hackneyed themes, not easy with all the mummy movies, Scorpion King, Raiders of the Lost Ark sort of cinema. Jennie’s Dead is not about Egypt, ancient or otherwise, but it plays an important role in the plot. Getting started is difficult, trying to sort out where the story wants to go, whether the main conflict is clear, to me and to the eventual reader.

Also moving forward, also slowly, with Reimagining. The pile of printed out posts has shrunk considerably, now filed. As I’ve gone through them, I read them a bit, for filing purposes. One notion that jumped out at me was my turn away from text-based religions, from the sort of quasi-scholastic reasoning that occurs.

As Emerson said, “Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe?”

As Emerson said, “Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe?”

I guess Emerson and I had the same quandary. We love the ancient texts, their poetry and philosophy, yet do not want to be bound by them. We want our poetry and revelation straight from the source, nature and the human experience of our own time. Yet, it seems to me, we’re both informed in our search for the poetry of existence by the way those seekers of the past found revelation in their time. Surely the logic of wanting our own revelation grounds itself in the stories of Genesis, the work of Moses, the resurrection story of Jesus, even the night flight of Muhammad and the whirling cosmic dance of Shiva.

This means I’m in a curious position relevant to my own education in the Christian tradition and my new education, underway now, in the older faith tradition of Judaism. Both are normative, in their way, but not as holy writ. Rather, they are normative in a more fundamental sense, they reveal the way we humans can discover the sacred as it wends and winds its way not only through the universe, but through history.

This means I’m in a curious position relevant to my own education in the Christian tradition and my new education, underway now, in the older faith tradition of Judaism. Both are normative, in their way, but not as holy writ. Rather, they are normative in a more fundamental sense, they reveal the way we humans can discover the sacred as it wends and winds its way not only through the universe, but through history.

We may not, in other words, be bound by their philosophy and insight, the history of their revelation, yet how the ancients made themselves open to the whispers and shouts of the sacred, how they received its insights and what use they made of it in their lives, those shape us because we are the same vessel, only thrown into a different time.

This is a similar idea to that of the reconstructionists, but not the same. Reconstructionists want to work with a constantly evolving Jewish civilization, grounding themselves in Torah, mussar, kabbalah, shabbat, the old holidays, but emphasizing the work of building a Jewish culture in the current day, reconstructing it as Jews change and the world around them changes, too. I’m learning so much from this radical idea.

This is a similar idea to that of the reconstructionists, but not the same. Reconstructionists want to work with a constantly evolving Jewish civilization, grounding themselves in Torah, mussar, kabbalah, shabbat, the old holidays, but emphasizing the work of building a Jewish culture in the current day, reconstructing it as Jews change and the world around them changes, too. I’m learning so much from this radical idea.

What I want to do though, and it’s a similar challenge, is to reimagine, for our time and as a dynamic, the way we reach for the sacred, the way we write about our experience, the way we celebrate the insights and the poetry it inspires. In this Reconstructionist Judaism is a better home for me than Unitarian Universalism. UU’s may have the same goal, but their net is cast into the vague sea of the past, trying to catch a bit from here and a bit from there. It is untethered, floating with no anchor. Beth Evergreen affirms the past, the texts of their ancestors, their thousands of years of interpretation, the holidays and the personal, daily life of a person shaped by this tradition, but also recognizes the need to live those insights in an evolving world.

What I want to do though, and it’s a similar challenge, is to reimagine, for our time and as a dynamic, the way we reach for the sacred, the way we write about our experience, the way we celebrate the insights and the poetry it inspires. In this Reconstructionist Judaism is a better home for me than Unitarian Universalism. UU’s may have the same goal, but their net is cast into the vague sea of the past, trying to catch a bit from here and a bit from there. It is untethered, floating with no anchor. Beth Evergreen affirms the past, the texts of their ancestors, their thousands of years of interpretation, the holidays and the personal, daily life of a person shaped by this tradition, but also recognizes the need to live those insights in an evolving world.