Samain Bare Aspen Moon

A word about fraternities. I was in one. Not of my choosing. Wabash College, where I spent my freshman year, required all freshmen to live on campus. There were dorms, but preference for dorm rooms went to upper classmen. (Wabash is all male.) The result: you had to pledge a fraternity. For reasons I neither recall nor care about, I ended up in Phi Kappa Psi. I mention this in particular because of an odd coincidence. A Phi Psi chapter in Texas just killed a pledge named Ellis.

It’s unclear right now whether alcohol was the culprit, but if it wasn’t, I’m sure it was a contributor. Binge drinking not only occurs in fraternities, it’s actively encouraged. While I don’t blame the Indiana gamma chapter for my subsequent alcoholism and 10 years of cigarette smoking, I certainly got my start in the chapter house in Crawfordsville, Indiana.

Being a pledge gives pledge masters an outsized influence over young men and women in their first year away from home. I suppose this could be good, helping initiate a student into campus life, gaining a new collection of brothers and sisters who understand college, it’s relentless complexity. It wasn’t good for me. My situation is a little unusual in that I had no desire to be a fraternity man, but ended being one anyhow. I was not enamored of nor looking for a fraternity. So I began jaundiced. And left the same way.

Being a pledge gives pledge masters an outsized influence over young men and women in their first year away from home. I suppose this could be good, helping initiate a student into campus life, gaining a new collection of brothers and sisters who understand college, it’s relentless complexity. It wasn’t good for me. My situation is a little unusual in that I had no desire to be a fraternity man, but ended being one anyhow. I was not enamored of nor looking for a fraternity. So I began jaundiced. And left the same way.

I’m not sure how college in the 1960’s compares to college now. It was a lot, lot different, I think, but Wabash, a more traditional place, was sort of a time capsule of old school ways. It sounds like fraternities have not changed much even now, over 50 years later.

Count me as a fraternity man against fraternities. Reinforced by the Texas incident.

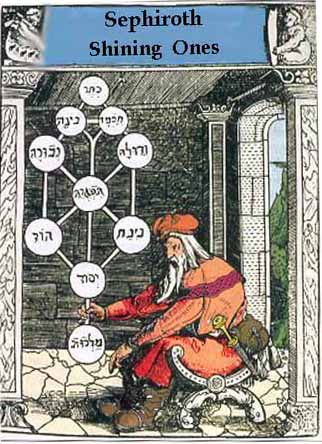

I spent time before the trip to Tony’s working on my kabbalah presentation for December 6th. This will take some doing since kabbalah is a quintessentially Jewish discipline and I want to focus, somehow, on the Great Wheel. According to the Tree of Life, the sephiroth (spheres) arranged as in this illustration reveal a path by which the sacred becomes actual and the actual becomes sacred. The bottom sephirot malkuth is the world which we experience daily, the place where all the power in this universe (there are many others), funnels out of the spiritual and into the ontological. It is also the realm of the shekinah, the feminine aspect of god. In kabbalistic terms malkuth is the place where the limits of things allow the pulsing, living energy of the other spheres to wink into existence.

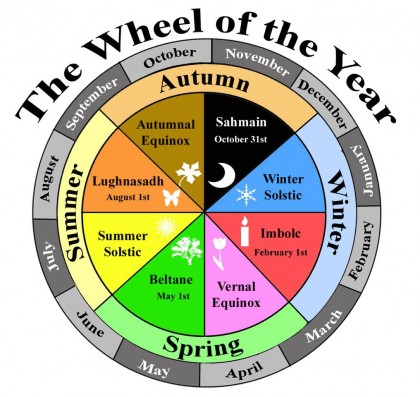

I spent time before the trip to Tony’s working on my kabbalah presentation for December 6th. This will take some doing since kabbalah is a quintessentially Jewish discipline and I want to focus, somehow, on the Great Wheel. According to the Tree of Life, the sephiroth (spheres) arranged as in this illustration reveal a path by which the sacred becomes actual and the actual becomes sacred. The bottom sephirot malkuth is the world which we experience daily, the place where all the power in this universe (there are many others), funnels out of the spiritual and into the ontological. It is also the realm of the shekinah, the feminine aspect of god. In kabbalistic terms malkuth is the place where the limits of things allow the pulsing, living energy of the other spheres to wink into existence. In one sense then the Great Wheel, focused as it is on this earth, can only be of malkuth, that is, of the sphere of the actual, the bottom circle below the hand of the kabbalist in the illustration. In another sense, since all sephiroth contain all others, what is of malkuth must also be of the others, the spiritual dna of the whole universe. So, if we take the Great Wheel as a metaphor for the creating, harvesting and ending of life, a cycle without end, then the Great Wheel is, too, a Tree of Life. That is, the inanimate becomes animate, the animate lives, then dies, returning its inanimate particulars to the universe which, through the power of ongoing creation, rearranges them in living form so the cycle can go on.

In one sense then the Great Wheel, focused as it is on this earth, can only be of malkuth, that is, of the sphere of the actual, the bottom circle below the hand of the kabbalist in the illustration. In another sense, since all sephiroth contain all others, what is of malkuth must also be of the others, the spiritual dna of the whole universe. So, if we take the Great Wheel as a metaphor for the creating, harvesting and ending of life, a cycle without end, then the Great Wheel is, too, a Tree of Life. That is, the inanimate becomes animate, the animate lives, then dies, returning its inanimate particulars to the universe which, through the power of ongoing creation, rearranges them in living form so the cycle can go on.