Lughnasa Harvest Moon

As the moon’s change, so does the Jewish calendar. We’re now in the month of Tishrei, its first day, Rosh Hashanah, the new year of the world. All over the world, throughout the diaspora and in Israel, Jews will be celebrating the new year, shana tovah. This is short for l’shana tova tikateyvu, “May you be written [in the Book of Life*] for a good year.”

As the moon’s change, so does the Jewish calendar. We’re now in the month of Tishrei, its first day, Rosh Hashanah, the new year of the world. All over the world, throughout the diaspora and in Israel, Jews will be celebrating the new year, shana tovah. This is short for l’shana tova tikateyvu, “May you be written [in the Book of Life*] for a good year.”

This is not, as may be inferred from the paragraph below, primarily a message of judgment. Rather, it is a call for cheshbon nefesh, an accounting of the soul. That is, instead of judgment, the focus is on introspection about the last year, honestly acknowledging areas of life where we’ve missed the mark and then, developing a plan for a new year that includes both atonement and teshuvah, return to a path of holiness. This is an iterative process, it happens every year because there is no achievement of perfection; but there is, as one writer said, the opportunity in this life to become very good.

The soul curriculum of mussar, Jewish ethics which focus on incremental gains in character virtues, acknowledges both the strengths we have and the areas where we can improve our character. “My practice, for example, for this month, for the middot (character virtue) of curiosity, is to greet judgement with curiosity. That is, each time I feel a judgement about another come up, I’ll add to that feeling a willingness to become curious about what motivated the behavior I’m judging, what might be the broader context? Am I being reactive or am I seeing something that does concern me? Or, both? Does my judgement say more about me than what I’m judging?”

I thought about two boys of a man I know. I pictured them both, slovenly and overweight, and thought, what went wrong with them? I had added to those two judgments an assumption that they were lazy, had not fulfilled whatever potential their father, a successful and kind man, hoped for. Since I don’t know either of them, it’s obvious this reaction said more about me than about them.

I thought about two boys of a man I know. I pictured them both, slovenly and overweight, and thought, what went wrong with them? I had added to those two judgments an assumption that they were lazy, had not fulfilled whatever potential their father, a successful and kind man, hoped for. Since I don’t know either of them, it’s obvious this reaction said more about me than about them.

However, I woke up to the judgment and used it as a prod for curiosity. What are they really like? Why did I make those assumptions? What about my own fears did this judgment express? That I’m not in good shape, that I don’t always present my best self? That I had not fulfilled my own potential? Ah. Well, there we are. My judgment was not about them at all, but about me. Yes, I’m curious to know more about them, to learn about their lives because they’re the sons of a man I respect; but, that particular curiosity is not the one most useful here. In this case the curiosity needs to be turned back on my own soul.

So, curiosity is on my soul curriculum. When I’m incurious, I tend to be judgmental. When I’m curious, I learn new things, I can adjust my behavior. Also, when we’re incurious, we simply don’t learn. Because there is no need. That reinforces our judgments and makes us slaves to our biases and prejudices. Curiosity can be a sort of soul broom, sweeping away our assumptions to make room for new insights, new relationships.

It is this hopeful, supportive type of cheshbon nefesh that the metaphor of the book of life and the book of death encourages. We can have a sweet new year, one dipped in honey, if we are honest, acknowledge our strengths, and work to add to them.

*The language of our prayers imagines God as judge and king, sitting in the divine court on the divine throne of justice, reviewing our deeds. On a table before God lies a large book with many pages, as many pages as there are people in the world. Each of us has a page dedicated just to us. Written on that page, by our own hand, in our own writing, are all the things we have done during the past year. God considers those things, weighs the good against the bad, and then, as the prayers declare, decides “who shall live and who shall die.”

Modern technology is so wonderful. Over the last few days I watched all five of the much maligned Twilight movies. You might ask why, at 71, I would subject myself to all those teen hormones, questionable dialogue, and odd acting. First answer, I’m easily entertained. Second answer, I’m revising Superior Wolf right now. Werewolves from their source. Also, a project I work on from time to time is Rocky Mountain Vampire. So, the Twilight saga is in the same genre as my own work, though aimed more at a young adult, tween to teen audience. Which is, I might add, a very lucrative market. Maybe, it just occurred to me, some of them will be interested in my work as a result of their exposure to the Twilight books and movies.

Modern technology is so wonderful. Over the last few days I watched all five of the much maligned Twilight movies. You might ask why, at 71, I would subject myself to all those teen hormones, questionable dialogue, and odd acting. First answer, I’m easily entertained. Second answer, I’m revising Superior Wolf right now. Werewolves from their source. Also, a project I work on from time to time is Rocky Mountain Vampire. So, the Twilight saga is in the same genre as my own work, though aimed more at a young adult, tween to teen audience. Which is, I might add, a very lucrative market. Maybe, it just occurred to me, some of them will be interested in my work as a result of their exposure to the Twilight books and movies. The supernatural is a dominant theme in my life, from religion to magic to ancient myths and legends to fairy tales and folklore. My world has enchantment around every bend, every mountain stream, every cloud covered mountain peak. No, I don’t know if there are faeries and elves and Shivas and Lokis and witches who eat children. I don’t know if anyone ever set out on a quest for the golden fleece or angels got thrown out of heaven. Don’t need to. We wonder about what happens after death, a common horror experience often and always. If we’re thoughtful, we wonder about what happened before life. Where were we before?

The supernatural is a dominant theme in my life, from religion to magic to ancient myths and legends to fairy tales and folklore. My world has enchantment around every bend, every mountain stream, every cloud covered mountain peak. No, I don’t know if there are faeries and elves and Shivas and Lokis and witches who eat children. I don’t know if anyone ever set out on a quest for the golden fleece or angels got thrown out of heaven. Don’t need to. We wonder about what happens after death, a common horror experience often and always. If we’re thoughtful, we wonder about what happened before life. Where were we before? Our senses limit us to a particular spectrum of light, a particular range of sounds, a particular grouping of smells and tastes, yet we know about the infrared, low and high frequency sounds, the more nuanced world of smells available to dogs. We’re locked inside our bodies, yet we know that there are multiverses in every person we meet, just like in us. We know we were thrown into a particular moment, yet know very little of the moments the other billions of us got thrown into. My point is that our understanding of the natural is very, very limited, in spite of all the sophisticated scientific and humanistic and technological tools we can bring to bear. Most of what exists is outside our usual understanding of natural, certainly outside our sensory experience.

Our senses limit us to a particular spectrum of light, a particular range of sounds, a particular grouping of smells and tastes, yet we know about the infrared, low and high frequency sounds, the more nuanced world of smells available to dogs. We’re locked inside our bodies, yet we know that there are multiverses in every person we meet, just like in us. We know we were thrown into a particular moment, yet know very little of the moments the other billions of us got thrown into. My point is that our understanding of the natural is very, very limited, in spite of all the sophisticated scientific and humanistic and technological tools we can bring to bear. Most of what exists is outside our usual understanding of natural, certainly outside our sensory experience. Spent most of yesterday on submissions. I revised School Spirit, taking 2.0 down to 2,700 words from 4,800, and submitted the revision to Mysterion. I developed a table in Word to track my submissions. It has these columns: submission, work, publisher, response, rejection, acceptance, contract, published. Later on today I’m going to begin revision of Superior Wolf, which I want to get out as soon as I can get it where I want it.

Spent most of yesterday on submissions. I revised School Spirit, taking 2.0 down to 2,700 words from 4,800, and submitted the revision to Mysterion. I developed a table in Word to track my submissions. It has these columns: submission, work, publisher, response, rejection, acceptance, contract, published. Later on today I’m going to begin revision of Superior Wolf, which I want to get out as soon as I can get it where I want it. So, I’m facing my fear, not only that, I’m leaning into it, grabbing it by the scruff of the neck and saying, “Come on, now. Message received. Stop already.” This is partly mussar driven, the practice I wrote about on

So, I’m facing my fear, not only that, I’m leaning into it, grabbing it by the scruff of the neck and saying, “Come on, now. Message received. Stop already.” This is partly mussar driven, the practice I wrote about on  Publishers and editors and agents, even critics and readers, are not lions or hyenas on the veldt. The fear I’ve allowed to rule me for the past three decades however has believed them so. The shame then is a complicated emotion which recognizes the self-deception and self-protection. It knows I’ve chosen the critique of intimates, why hasn’t Charlie ever published, to the critique of possible readers. That’s embarrassing, but it’s where I’ve been for a long, long time.

Publishers and editors and agents, even critics and readers, are not lions or hyenas on the veldt. The fear I’ve allowed to rule me for the past three decades however has believed them so. The shame then is a complicated emotion which recognizes the self-deception and self-protection. It knows I’ve chosen the critique of intimates, why hasn’t Charlie ever published, to the critique of possible readers. That’s embarrassing, but it’s where I’ve been for a long, long time. I know that fear vitiates trust. If we’re afraid of another person’s motives, we’ll never get to know them well. If we’re afraid of public speaking, no one will hear us. If we’re afraid of our own motives, we’ll take few risks. In these cases, if we face the fear, listen to it, talk it down, choose to act differently, then we may find love, may discover that people want to know what we have to say, may open ourselves to the world’s rich opportunities.

I know that fear vitiates trust. If we’re afraid of another person’s motives, we’ll never get to know them well. If we’re afraid of public speaking, no one will hear us. If we’re afraid of our own motives, we’ll take few risks. In these cases, if we face the fear, listen to it, talk it down, choose to act differently, then we may find love, may discover that people want to know what we have to say, may open ourselves to the world’s rich opportunities.

Ouch. I got this note back:

Ouch. I got this note back: Then, I paused. Wait. This is the moment I wanted. Lean into the shame and embarrassment, see what it means. Why do I feel that way? So many reasons. Personal competence. A big risk taken with no results. Kate’s been so supportive of my writing. Most of all though it’s my work, being rejected. And it feels bad.

Then, I paused. Wait. This is the moment I wanted. Lean into the shame and embarrassment, see what it means. Why do I feel that way? So many reasons. Personal competence. A big risk taken with no results. Kate’s been so supportive of my writing. Most of all though it’s my work, being rejected. And it feels bad. Not sure here all of a sudden. It was shame that I felt when I read this note. Didn’t realize it, name it until I began writing this. Why though? Why shame? Perhaps it’s from that old, underlying conundrum, am I living up to my potential? Who’s to say? Perhaps it’s wanting to be seen as a creative person, a writer of books, yet secretly suspecting that I’m not worthy of those identifiers. Perhaps it’s as simple as failing and being ashamed of failing?

Not sure here all of a sudden. It was shame that I felt when I read this note. Didn’t realize it, name it until I began writing this. Why though? Why shame? Perhaps it’s from that old, underlying conundrum, am I living up to my potential? Who’s to say? Perhaps it’s wanting to be seen as a creative person, a writer of books, yet secretly suspecting that I’m not worthy of those identifiers. Perhaps it’s as simple as failing and being ashamed of failing? What I do know, for sure, is that this shame, a hot desire to hide, to cover myself, to flee works against me, is not for me, in any way. And I could identify that paradox in another, in Kate or one of the Woollys, or a friend at Beth Evergreen. I would have compassion for it, yet also have a tough love move against it. It’s not who you are, it’s an attack on yourself from within. Perhaps we could call it Shaitan, the Devil because it is evil to push yourself down or to push another person down. Why? Because living is all we have and shame makes us shrink from life.

What I do know, for sure, is that this shame, a hot desire to hide, to cover myself, to flee works against me, is not for me, in any way. And I could identify that paradox in another, in Kate or one of the Woollys, or a friend at Beth Evergreen. I would have compassion for it, yet also have a tough love move against it. It’s not who you are, it’s an attack on yourself from within. Perhaps we could call it Shaitan, the Devil because it is evil to push yourself down or to push another person down. Why? Because living is all we have and shame makes us shrink from life. At the Mussar Vaad Practice group we all come up with a practice for the coming month, a practice based on that month’s middah or character trait. Each month the congregation has a middah of the month. Emunah, or faith was the middah last month. My practice focused on sharpening doubt, a practice that made me feel more alive, more grounded in faith as a necessary human act.

At the Mussar Vaad Practice group we all come up with a practice for the coming month, a practice based on that month’s middah or character trait. Each month the congregation has a middah of the month. Emunah, or faith was the middah last month. My practice focused on sharpening doubt, a practice that made me feel more alive, more grounded in faith as a necessary human act.

That same fear is the one I faced after the Durango trip, writing

That same fear is the one I faced after the Durango trip, writing  I’m embarrassed to write this, ashamed I’ve been so fearful, yet I have been both embarrassed and ashamed for most of the most of the time I’ve been writing. Now is not different. The only way I can make it different is by finding publishers and agents and getting my work to them.

I’m embarrassed to write this, ashamed I’ve been so fearful, yet I have been both embarrassed and ashamed for most of the most of the time I’ve been writing. Now is not different. The only way I can make it different is by finding publishers and agents and getting my work to them.

Here’s the key idea, from Mordecai Kaplan: the past gets a vote, but not a veto. That is, when considering tradition, in Kaplan’s case of course Jewish tradition, the tradition itself informs the present, but we are not required to obey it. Instead we can change it, or negate it, or choose to accept, for now, its lesson.

Here’s the key idea, from Mordecai Kaplan: the past gets a vote, but not a veto. That is, when considering tradition, in Kaplan’s case of course Jewish tradition, the tradition itself informs the present, but we are not required to obey it. Instead we can change it, or negate it, or choose to accept, for now, its lesson. Which brings me to another realization I had this week. Just like environmental action is not about saving the planet, the planet will be fine, it’s about saving humanity’s spot on the planet; the idea of living in the moment is not about living in the moment, it’s about remembering we can do no other thing than live in the moment.

Which brings me to another realization I had this week. Just like environmental action is not about saving the planet, the planet will be fine, it’s about saving humanity’s spot on the planet; the idea of living in the moment is not about living in the moment, it’s about remembering we can do no other thing than live in the moment. The past is gone, the future is not yet. Always. We can be sure, confident, only of this instance, for the next may not come. To be aware of the moment is to be aware of both the tenuousness of life, and its vitality, which also occurs only in the moment. To know this, really know it in our bones, means we must have faith that the next moment will arrive, because it is not given. Not only is it not given, it will, someday, not arrive for us. That’s where faith comes in, living in spite of that knowledge, living as if the next moment is on its way.

The past is gone, the future is not yet. Always. We can be sure, confident, only of this instance, for the next may not come. To be aware of the moment is to be aware of both the tenuousness of life, and its vitality, which also occurs only in the moment. To know this, really know it in our bones, means we must have faith that the next moment will arrive, because it is not given. Not only is it not given, it will, someday, not arrive for us. That’s where faith comes in, living in spite of that knowledge, living as if the next moment is on its way. Probably not many folks count down to the Summer Solstice, but I do. It marks my favorite turning point in the year, the point when the dark begins to overtake the light. Yes, it’s the day of maximum daylight, but that’s just the point, maximum. After the summer solstice, nighttime begins a slow, gradual increase until my favorite holiday of the year, the Winter Solstice.

Probably not many folks count down to the Summer Solstice, but I do. It marks my favorite turning point in the year, the point when the dark begins to overtake the light. Yes, it’s the day of maximum daylight, but that’s just the point, maximum. After the summer solstice, nighttime begins a slow, gradual increase until my favorite holiday of the year, the Winter Solstice. Summer and the light has its charms and its importance, too, of course. A warm summer evening. The growing season. The ability to see with clarity. The sun is a true god without whose beneficence we would all die. Worthy of our devotion. And, btw, our faith. So I get it, you sun worshipers. My inner compass swings in a different, an obverse direction.

Summer and the light has its charms and its importance, too, of course. A warm summer evening. The growing season. The ability to see with clarity. The sun is a true god without whose beneficence we would all die. Worthy of our devotion. And, btw, our faith. So I get it, you sun worshipers. My inner compass swings in a different, an obverse direction. One of us in the group last night said, “The universe is for me.” I have other friends who believe the universe is a place of abundance, or, as author

One of us in the group last night said, “The universe is for me.” I have other friends who believe the universe is a place of abundance, or, as author  Turns out quite a lot. Another of us last night told a story of night diving. A favorite activity of hers. She said she turns off her diving light and floats in the night dark ocean. While she’s in the dark, she imagines a shark behind her. The shark may kill her in the next moment, but until that moment she is keenly alive. This is, for me, a perfect metaphor for faith. Each day the shark is behind us. A car accident. A heart attack. A lightening bolt. A terminal diagnosis. Yet each day we float in the dark, suspended between this moment in which we live and the next one in which we are dead. And we rejoice in that moment. There is faith.

Turns out quite a lot. Another of us last night told a story of night diving. A favorite activity of hers. She said she turns off her diving light and floats in the night dark ocean. While she’s in the dark, she imagines a shark behind her. The shark may kill her in the next moment, but until that moment she is keenly alive. This is, for me, a perfect metaphor for faith. Each day the shark is behind us. A car accident. A heart attack. A lightening bolt. A terminal diagnosis. Yet each day we float in the dark, suspended between this moment in which we live and the next one in which we are dead. And we rejoice in that moment. There is faith. This is the existentialist abyss of which Nietzsche famously said, “If you stare into the abyss, the abyss stares back at you.” Living on in spite of its direct glare, that’s faith. This sort of faith requires no confidence in the good or ill will of the universe, it requires what Paul Tillich called the courage to be. I would challenge that formulation a bit by altering it to the courage to become, but the point is the same.

This is the existentialist abyss of which Nietzsche famously said, “If you stare into the abyss, the abyss stares back at you.” Living on in spite of its direct glare, that’s faith. This sort of faith requires no confidence in the good or ill will of the universe, it requires what Paul Tillich called the courage to be. I would challenge that formulation a bit by altering it to the courage to become, but the point is the same. So. My practice for this month involves, in Rabbi Jamie’s phrase, sharpening my doubt. I will remember the shark as often as I can. I will recognize the contingent nature of every action I take, of every aspect of my life. And live into those contingencies, act as if the shark will let me be right now. As if the uncertainty of driving, of interacting with others, of our dog’s lives will not manifest right now. That’s faith. Action in the face of contingency. Action in the face of uncertainty. Action in the face of doubt.

So. My practice for this month involves, in Rabbi Jamie’s phrase, sharpening my doubt. I will remember the shark as often as I can. I will recognize the contingent nature of every action I take, of every aspect of my life. And live into those contingencies, act as if the shark will let me be right now. As if the uncertainty of driving, of interacting with others, of our dog’s lives will not manifest right now. That’s faith. Action in the face of contingency. Action in the face of uncertainty. Action in the face of doubt.

My presentation on time falls under the sumi-e moon and I plan to use sumi-e. I’m taking my brushes, ink, ink stones, red ink pad, Kraft paper, and rice paper. As well as my hourglasses. I will do Shakespeare’s soliloquy from Macbeth as a counter point. Each person will first practice an enso on the Kraft paper, then do one on rice paper.

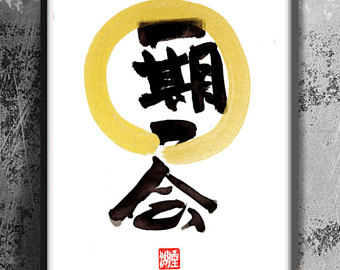

My presentation on time falls under the sumi-e moon and I plan to use sumi-e. I’m taking my brushes, ink, ink stones, red ink pad, Kraft paper, and rice paper. As well as my hourglasses. I will do Shakespeare’s soliloquy from Macbeth as a counter point. Each person will first practice an enso on the Kraft paper, then do one on rice paper. What is an enso? The word means circle in Japanese. In Zen it has a much more expansive meaning.* Zen is, of course, Chan Buddhism, a curious blend of Taoism and Buddhism created in China. Monks from Japan went to China to learn about Chan and brought it back to Japan. They also brought back the practice of drinking tea, which initially was a stimulant to help with long meditation sessions. It later transmogrified into the Japanese tea ceremony with its beautiful idea of ichi go ichi e, or once in a lifetime.

What is an enso? The word means circle in Japanese. In Zen it has a much more expansive meaning.* Zen is, of course, Chan Buddhism, a curious blend of Taoism and Buddhism created in China. Monks from Japan went to China to learn about Chan and brought it back to Japan. They also brought back the practice of drinking tea, which initially was a stimulant to help with long meditation sessions. It later transmogrified into the Japanese tea ceremony with its beautiful idea of ichi go ichi e, or once in a lifetime.