Winter Imbolc Moon

This is, I know, a terrible picture, although since it was taken at night, with my hand held computing device and from a considerable distance away-I was parked at the side of the road hoping no one would stovepipe me-it’s ok.

This is, I know, a terrible picture, although since it was taken at night, with my hand held computing device and from a considerable distance away-I was parked at the side of the road hoping no one would stovepipe me-it’s ok.

This tree is my favorite light display along Brook Forest Drive on the way to Evergreen. There were many. The folks who lit it up must have run a very long extension cord to get to it, because it sits all alone in the woods, on the edge of a precipice. I love its existential isolation and yet its brilliance and its color.

The woods up here, the Arapaho National Forest for the most part, are lovely dark and deep and beautiful because of that, but having this small bit of human intervention tickles me.

It’s a part of a larger picture that’s coming to me. When I mentioned shamanic seeing in the post about the mountain spirits, it made me aware that I need to a third R to my gerundal theology: reimagining and reconstructing AND re-enchanting. This last of the three R’s of an emerging approach to faith may be the most important of all. The first two involve rational heavy lifting, taking something apart and putting it back together in a way meaningful today. Important and critical, yes. But, I’m realizing, not enough.

More than the intellectual work we need the emotional work, a return to shamanic seeing, a return to a view of the world as a magical, mystical place. Which it always has been and continues to be. The empirical method, the scientific method has, like religious dogma, occluded our ability to see wonder. One woman said, during the mussar class in which we discussed the three messengers (angels) from the mountain spirit, said, “How would the mountain know when to send out the messengers?” Beep. Wrong question.

More than the intellectual work we need the emotional work, a return to shamanic seeing, a return to a view of the world as a magical, mystical place. Which it always has been and continues to be. The empirical method, the scientific method has, like religious dogma, occluded our ability to see wonder. One woman said, during the mussar class in which we discussed the three messengers (angels) from the mountain spirit, said, “How would the mountain know when to send out the messengers?” Beep. Wrong question.

The right question? How can we open our hearts to the intimate communication we get from the natural world everyday? Including those emanating from within our own bodies. It’s our perception that needs to change, not the world. It’s still sending messengers and messages, but we’ve systematically tricked ourselves into thinking we now know too much to attend to them. We don’t.

What does that lenticular cloud hanging over Black Mountain have to say? How about the wind howling down off Mt. Evans? The snow storm about to hit us? The fox or the mountain lion or the bear crossing our yard? The gradual decline of our muscle mass, our mental mass, as we age? Where are our faeries? Why won’t the wood nymphs of the lodgepole pines speak to me? The sun and its perpetual light. That rock fallen on to the road. What do they mean? Not what are they? Not why are they there? But what love note from the big bang do they contain? How would the ancient Greek or the Hebrew on Sinai or the folk who walked up out of Africa relate to them?

What does that lenticular cloud hanging over Black Mountain have to say? How about the wind howling down off Mt. Evans? The snow storm about to hit us? The fox or the mountain lion or the bear crossing our yard? The gradual decline of our muscle mass, our mental mass, as we age? Where are our faeries? Why won’t the wood nymphs of the lodgepole pines speak to me? The sun and its perpetual light. That rock fallen on to the road. What do they mean? Not what are they? Not why are they there? But what love note from the big bang do they contain? How would the ancient Greek or the Hebrew on Sinai or the folk who walked up out of Africa relate to them?

No, we don’t have to give up the scientific. No, we don’t have to abjure missing the rock with our car or truck. We only have to ask about our relationship with all these. What is it? How does it convey meaning to me? I like the notion of spirits and gods, goddesses, too. I’m still looking for the Great God Pan. Maybe you’ve seen him?

“The more I have looked into the Quest for the Grail, it is clear it is a Western form of Zen. There is no grail, it is understanding that the veil is the mystery of existence, it is nothing, but our interactions with everyone and everything.” Woolly and friend, Mark Odegard

“The more I have looked into the Quest for the Grail, it is clear it is a Western form of Zen. There is no grail, it is understanding that the veil is the mystery of existence, it is nothing, but our interactions with everyone and everything.” Woolly and friend, Mark Odegard

The Woolly Mammoths have been my companions, fellow pilgrims, on the way to Canterbury. Or, fellow Tibetan Buddhists inch worming their way around the sacred mountain, Meru. Or, my fellow Torah scholars, davening as we read the sacred texts. Or, fellow Lakotas, our skin pierced and tied to the world tree during the Sun Dance. Or, friends traveling through this life together until it ends.

The Woolly Mammoths have been my companions, fellow pilgrims, on the way to Canterbury. Or, fellow Tibetan Buddhists inch worming their way around the sacred mountain, Meru. Or, my fellow Torah scholars, davening as we read the sacred texts. Or, fellow Lakotas, our skin pierced and tied to the world tree during the Sun Dance. Or, friends traveling through this life together until it ends.

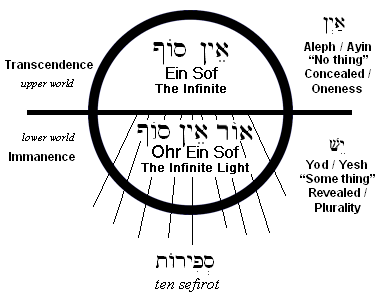

No. God is another word for the intimate linkage between and among all things, from the smallest gluon to the largest star. God is neither a superparent nor a cosmic Santa Claus writing down your behaviors in the book of deeds; God is a metaphor for the sacred knowledge which permeates the perceivable, and the unperceivable, world.

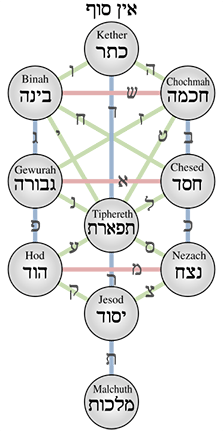

No. God is another word for the intimate linkage between and among all things, from the smallest gluon to the largest star. God is neither a superparent nor a cosmic Santa Claus writing down your behaviors in the book of deeds; God is a metaphor for the sacred knowledge which permeates the perceivable, and the unperceivable, world. Kabbalah last night. The first session of Mystical Hebrew Letters. Rabbi Jamie began teaching kabbalah at the Kabbalah Experience with this class several years ago. It moves from the broader conceptual fields of Soul and Space, the first two classes this year, to the particular examination of the Hebrew alphabet.

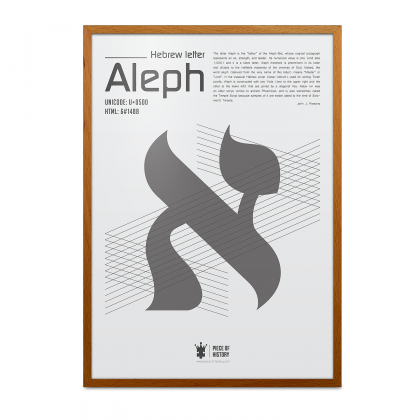

Kabbalah last night. The first session of Mystical Hebrew Letters. Rabbi Jamie began teaching kabbalah at the Kabbalah Experience with this class several years ago. It moves from the broader conceptual fields of Soul and Space, the first two classes this year, to the particular examination of the Hebrew alphabet. Aleph, the first letter, was an ox-head. The word aleph means ox-head, or head of ox, also learning and chieftain. Prior to the use of Arabic numerals each Hebrew letter stood in for numbers with the letter aleph as number one. The word aleph means 1,000. Thus, aleph symbolizes the philosophical notion of the one and the many.

Aleph, the first letter, was an ox-head. The word aleph means ox-head, or head of ox, also learning and chieftain. Prior to the use of Arabic numerals each Hebrew letter stood in for numbers with the letter aleph as number one. The word aleph means 1,000. Thus, aleph symbolizes the philosophical notion of the one and the many.

Inside the particular Jewish or Presbyterian or Unitarian or New Thought or Tibetan Buddhist or Hindu or Muslim community to which we belong we use this language and create a sense of belonging. As we use the language, part of which is ritual and dress, part of which is expected behaviors, we create a semi-permeable membrane, often not very permeable at all, for outsiders. To cross into our community they have to penetrate the language, learn the customs, adjust themselves to the patterns. The membrane works both ways, obscuring our vision as we look out from within our particular tradition. We see a world shaped by and often determined by the assumptions of ours.

Inside the particular Jewish or Presbyterian or Unitarian or New Thought or Tibetan Buddhist or Hindu or Muslim community to which we belong we use this language and create a sense of belonging. As we use the language, part of which is ritual and dress, part of which is expected behaviors, we create a semi-permeable membrane, often not very permeable at all, for outsiders. To cross into our community they have to penetrate the language, learn the customs, adjust themselves to the patterns. The membrane works both ways, obscuring our vision as we look out from within our particular tradition. We see a world shaped by and often determined by the assumptions of ours.

The solstices mark swings to and from extremes, from the longest day to the longest night, there, and as with Bilbo, back again. Darkness and light are never steady in their presence. The earth always shifts in relation to the sun, gradually lengthening the days, then the nights.

The solstices mark swings to and from extremes, from the longest day to the longest night, there, and as with Bilbo, back again. Darkness and light are never steady in their presence. The earth always shifts in relation to the sun, gradually lengthening the days, then the nights. Winter break continues. The identity crisis has passed as I knew it would. The crisis focused on my passive choices, taking the path of least resistance after college and I did do that, giving up my intentionality about career to a socialization experience with clergy-focused fellow students. But. Within that decision to just follow the education I had chosen as a way to get out of a dead end job and an unhappy marriage, I was intentional.

Winter break continues. The identity crisis has passed as I knew it would. The crisis focused on my passive choices, taking the path of least resistance after college and I did do that, giving up my intentionality about career to a socialization experience with clergy-focused fellow students. But. Within that decision to just follow the education I had chosen as a way to get out of a dead end job and an unhappy marriage, I was intentional.

In the darkness we can attend to the dark things within us, the places in our souls where our own origins and their ongoing impacts create a climate for our growth, down below the conscious considerations of our day-to-day lives. We can embrace this darkness, not as a thing to fear, but as a part of life, a necessary and fruitful part of life.

In the darkness we can attend to the dark things within us, the places in our souls where our own origins and their ongoing impacts create a climate for our growth, down below the conscious considerations of our day-to-day lives. We can embrace this darkness, not as a thing to fear, but as a part of life, a necessary and fruitful part of life.