Midsommar Most Heat Moon

What looked like a nasty fire season in March and early April has become moderate, even subdued. First we had heavy late season snow, then rains and now cool weather. None of this rules out fire, but the fuel is moist and the temperatures are not exacerbating the low humidity. There are still emergency preparedness items to check off, however. Need to get that safety deposit box and figure out how to handle the times when one of us is away from the house with the car. A bit less urgency than we’d anticipated.

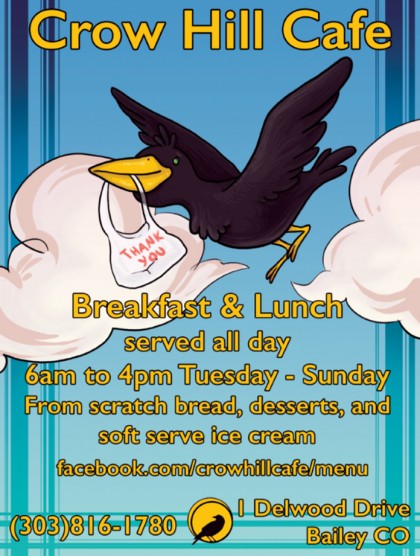

The go-go girls, Rigel and Gertie, joined me on a breakfast outing to Crow Hill Cafe. Crow Hill is the steep, 7% grade, that takes Hwy 285 down into Bailey. On the way there, from the western edge of Conifer, the continental divide defines the horizon, peaks until recently covered with snow. They allow us, who live in the mountains, to see the mountains in the same way folks in Denver can see the Front Range, as distant and majestic.

The go-go girls, Rigel and Gertie, joined me on a breakfast outing to Crow Hill Cafe. Crow Hill is the steep, 7% grade, that takes Hwy 285 down into Bailey. On the way there, from the western edge of Conifer, the continental divide defines the horizon, peaks until recently covered with snow. They allow us, who live in the mountains, to see the mountains in the same way folks in Denver can see the Front Range, as distant and majestic.

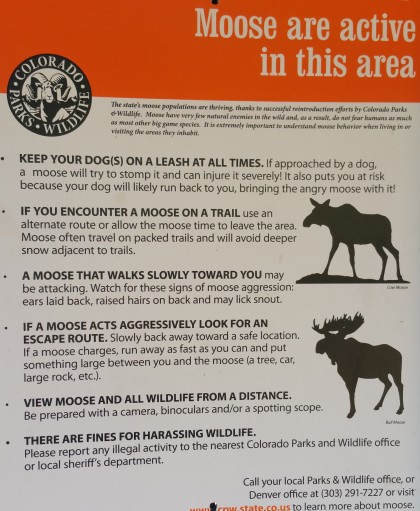

We experience the mountains daily, going up and down them, around their curvy two-lane roads, beside their creeks, outlets for snow melt, modulating our speed for the wildlife that refuses (thankfully) to acknowledge our presence as a limitation. This in the mountains travel finds our views obscured by the peaks that are close by and the valleys that we use to navigate through them.

French toast and crisp bacon, black coffee and the Denver Post, a window seat overlooking the slight rise beyond which Crow Hill plummets toward Bailey. I love eating breakfast out, don’t know why. Something about starting the day that way once in awhile. Rigel and Gertie got a saved piece of french toast each, happy dogs.

Back to Conifer and the King Sooper. King Sooper is a Kroger chain upscale store, one listed as a potentially threatened species by newspaper articles about Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods. With the rapid concentration of certain retail activities we may need an endangered business protection act. King Sooper does deliver though we’ve not made use of that service. Those of us on Shadow Mountain don’t expect to see drones with celery and milk anytime soon.

Back to Conifer and the King Sooper. King Sooper is a Kroger chain upscale store, one listed as a potentially threatened species by newspaper articles about Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods. With the rapid concentration of certain retail activities we may need an endangered business protection act. King Sooper does deliver though we’ve not made use of that service. Those of us on Shadow Mountain don’t expect to see drones with celery and milk anytime soon.

Although. We did have confirmation yesterday of a premium asset related to our location on Black Mountain Drive. Two Jefferson County sheriff black and white S.U.V.s followed an Elk Creek Fire and Rescue ambulance past us in the late afternoon yesterday. About 30 minutes later Kep recruited Rigel and Gertie to defend the house. When I went to check, there was a line-up of stopped vehicles stretching from the curve where Shadow Mountain Drive turns into Black Mountain Drive.

Neighbors and their dogs were on the sides of the road. Cell phones (pocket digital cameras) were out and aimed at the curve. The chop chop chop of helicopter rotors was evident, but the helicopter itself was not in sight. Then it was, slowly rising from the road, Flight for Life spelled out along the yellow stripe leading back to its stabilizers.

Neighbors and their dogs were on the sides of the road. Cell phones (pocket digital cameras) were out and aimed at the curve. The chop chop chop of helicopter rotors was evident, but the helicopter itself was not in sight. Then it was, slowly rising from the road, Flight for Life spelled out along the yellow stripe leading back to its stabilizers.

It’s very reassuring to know if Kate and I ever end up in a medical emergency we won’t have to rely on a 45 minute ambulance ride to the nearest E.R. The E.M.T.s could just pop us on a gurney, wheel us down the road a bit and into the ‘copter. Then up, up and away.

Today is back to working out, more reimagining prep, this time including reordering my reimagining bookshelf, checking the old computer for reimagining files. I’ll also be studying for kabbalah tomorrow night and possibly taking a trip over to Sundance nursery in Evergreen looking for lilac bushes.

Kabbalah. Reread Genesis 1-2:3. Now, ask yourself a question that occurred to a long ago kabbalist. What is the light created on the first day of creation? We know it’s not the sun or the moon or the stars because they don’t blink on until the 4th day, 1:14-19. So what is the ohr (light) of verse 3. “And God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light.”?

Kabbalah. Reread Genesis 1-2:3. Now, ask yourself a question that occurred to a long ago kabbalist. What is the light created on the first day of creation? We know it’s not the sun or the moon or the stars because they don’t blink on until the 4th day, 1:14-19. So what is the ohr (light) of verse 3. “And God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light.”? It’s a very bright group around the table: a historian, a Berkeley trained lawyer, an organizational consultant, a Hebrew scholar, a rabbi in training, a second lawyer, a teenager with a good grasp of theoretical physics, two retired hospital administrators. This makes the conversation sparky, inspirational.

It’s a very bright group around the table: a historian, a Berkeley trained lawyer, an organizational consultant, a Hebrew scholar, a rabbi in training, a second lawyer, a teenager with a good grasp of theoretical physics, two retired hospital administrators. This makes the conversation sparky, inspirational. As our habitable space ship races along its track, its tilt gives us seasonal changes and four regular moments, two with roughly equal days and nights, the equinoxes, and two extremes: the solstices. The longest days of the year occur right now with the sun rising early and setting late ignoring Benjamin Franklin’s early to bed, early to rise. Six months from now, in the depths of midwinter, we will have the winter solstice where darkness prevails and long nights are the rule.

As our habitable space ship races along its track, its tilt gives us seasonal changes and four regular moments, two with roughly equal days and nights, the equinoxes, and two extremes: the solstices. The longest days of the year occur right now with the sun rising early and setting late ignoring Benjamin Franklin’s early to bed, early to rise. Six months from now, in the depths of midwinter, we will have the winter solstice where darkness prevails and long nights are the rule. At midsommar in the temperate latitudes where farms dominate the landscape, the growing season, which began roughly around Beltane, is now well underway. Wheat, corn, barley, soybeans, sorghum, sunflowers have risen from seed and fed by rain or irrigation make whole landscapes green with the intense colors of full growth. Midsommar mother earth once again works hard to feed her children.

At midsommar in the temperate latitudes where farms dominate the landscape, the growing season, which began roughly around Beltane, is now well underway. Wheat, corn, barley, soybeans, sorghum, sunflowers have risen from seed and fed by rain or irrigation make whole landscapes green with the intense colors of full growth. Midsommar mother earth once again works hard to feed her children. Our seasonal dance is not only, not even mostly, a metaphor, but is itself the rhythm of life. When its regularities falter, when either natural or artificial forces alter it, even a little, whole peoples, whole ecosystems experience stress, often death. We humans, as the Iroquois know, are ultimately fragile, our day to day lives dependent on the plant life and animal life around us. When they suffer, we begin to fail.

Our seasonal dance is not only, not even mostly, a metaphor, but is itself the rhythm of life. When its regularities falter, when either natural or artificial forces alter it, even a little, whole peoples, whole ecosystems experience stress, often death. We humans, as the Iroquois know, are ultimately fragile, our day to day lives dependent on the plant life and animal life around us. When they suffer, we begin to fail. The meaning of the Great Wheel, it’s rhythms, remains the same, a faithful cycling through earth’s changes as it plunges through dark space on its round. Their implications though, thanks to climate change, may shift, will shift in response to new temperature, moisture regimes. The summer solstice may be the moment each year when we begin, again, to realize the enormity of those shifts. It might be that the summer solstice will require new rituals, ones focused on gathering our power to both adapt to those shifts and alleviate the human actions ratcheting up the risks.

The meaning of the Great Wheel, it’s rhythms, remains the same, a faithful cycling through earth’s changes as it plunges through dark space on its round. Their implications though, thanks to climate change, may shift, will shift in response to new temperature, moisture regimes. The summer solstice may be the moment each year when we begin, again, to realize the enormity of those shifts. It might be that the summer solstice will require new rituals, ones focused on gathering our power to both adapt to those shifts and alleviate the human actions ratcheting up the risks.

The shift to Reimagining has happened faster than I thought it would. My mind is like Kepler, our only dog who likes toys. He has a whole box of toys and he goes into it, noses around, finds the one he likes (why that one? no idea.), takes it out and carries it over to a place he’s decided is his toy stash area. I have several ideas that I’ve been playing with for years, e.g. becoming native to this place, emergence, tactile spirituality. In ways I don’t understand my mind goes over to the box of these ideas, hunts around, selects one and puts it front and center for maybe a second, maybe longer. Sometimes I pick up and play with one for awhile.

The shift to Reimagining has happened faster than I thought it would. My mind is like Kepler, our only dog who likes toys. He has a whole box of toys and he goes into it, noses around, finds the one he likes (why that one? no idea.), takes it out and carries it over to a place he’s decided is his toy stash area. I have several ideas that I’ve been playing with for years, e.g. becoming native to this place, emergence, tactile spirituality. In ways I don’t understand my mind goes over to the box of these ideas, hunts around, selects one and puts it front and center for maybe a second, maybe longer. Sometimes I pick up and play with one for awhile. In the shower one day I began to wonder where our water came from. At the time Kate and I lived on Edgcumbe Avenue in St. Paul so the question really was, where did St. Paul get its water? I had no idea. Turns out St. Paul public works pumps water out of the Mississippi and into a chain of lakes including Pleasant Lake and Sucker Lake just across the Anoka County border in Ramsey County north of St. Paul.

In the shower one day I began to wonder where our water came from. At the time Kate and I lived on Edgcumbe Avenue in St. Paul so the question really was, where did St. Paul get its water? I had no idea. Turns out St. Paul public works pumps water out of the Mississippi and into a chain of lakes including Pleasant Lake and Sucker Lake just across the Anoka County border in Ramsey County north of St. Paul. Though I haven’t done it, it would be possible to track back much further to the arrival of water on earth. This is a very interesting topic which I raise only to demonstrate the potential in this kind of thinking.

Though I haven’t done it, it would be possible to track back much further to the arrival of water on earth. This is a very interesting topic which I raise only to demonstrate the potential in this kind of thinking. Open the refrigerator. Where did the food come from? How about the carpet on your floor? The roofing material. Concrete. Paint. How about the car in your garage? Where was it built? What sort of materials go into making it? Where do they come from?

Open the refrigerator. Where did the food come from? How about the carpet on your floor? The roofing material. Concrete. Paint. How about the car in your garage? Where was it built? What sort of materials go into making it? Where do they come from? The incredible complexity of this web has put a thick wall between our daily lives and the earthiness of all that is around us. We start the car, shift into drive and head out to work or the store or on vacation dulled to the effort expended on the gasoline that fuels it, the rubber in the tires, the precious metals and the not-so precious metals in the body and frame and engine. I’m not talking right now about a car’s implication in climate change, or economic injustice, or urban planning. I’m focusing on getting to know how it came to be, what of our world made it possible.

The incredible complexity of this web has put a thick wall between our daily lives and the earthiness of all that is around us. We start the car, shift into drive and head out to work or the store or on vacation dulled to the effort expended on the gasoline that fuels it, the rubber in the tires, the precious metals and the not-so precious metals in the body and frame and engine. I’m not talking right now about a car’s implication in climate change, or economic injustice, or urban planning. I’m focusing on getting to know how it came to be, what of our world made it possible. Why? Because focusing on these things, deconstructing our things, begins to break the spell of modernism. Modernism offers us in the developed world a world prepackaged for our needs, organized so that we don’t have to till the field anymore, or hitch up the horse, or drop a bucket down a well. In so doing it waves the wand of mystification over our senses, blinding us to the mines, the aquifers, the oil fields, the vegetable fields, the landfills, the seeds and chemicals required to sustain us. This enchantment is the first barrier to a reimagined faith, to placing ourselves once again in the world.

Why? Because focusing on these things, deconstructing our things, begins to break the spell of modernism. Modernism offers us in the developed world a world prepackaged for our needs, organized so that we don’t have to till the field anymore, or hitch up the horse, or drop a bucket down a well. In so doing it waves the wand of mystification over our senses, blinding us to the mines, the aquifers, the oil fields, the vegetable fields, the landfills, the seeds and chemicals required to sustain us. This enchantment is the first barrier to a reimagined faith, to placing ourselves once again in the world. With the first draft of Superior Wolf finished I’m taking this week to do various tasks up in the loft that I’ve deferred. Gonna hang some art, rearrange some (by categories like Latin American, contemporary, Asian) and bring order to some of my disorganized book shelves. I want to get some outside work in, too, maybe get back to limbing and do some stump cutting, check out nurseries for lilac bushes.

With the first draft of Superior Wolf finished I’m taking this week to do various tasks up in the loft that I’ve deferred. Gonna hang some art, rearrange some (by categories like Latin American, contemporary, Asian) and bring order to some of my disorganized book shelves. I want to get some outside work in, too, maybe get back to limbing and do some stump cutting, check out nurseries for lilac bushes. Even so, reimagining is beginning to exert a centripetal force on my thinking, book purchasing, day to day. For example, last night as I went to sleep a cool breeze blew in from the north across my bare arms and shoulder. It was the night itself caressing me. I went from there to the sun’s warm caresses on a late spring day. The embrace of the ocean or a lake or a stream. The support given to our daily walking by the surface of mother earth. The uplift we experience on Shadow Mountain, 8,800 feet above sea level. These are tactile realities, often felt (0r their equivalent).

Even so, reimagining is beginning to exert a centripetal force on my thinking, book purchasing, day to day. For example, last night as I went to sleep a cool breeze blew in from the north across my bare arms and shoulder. It was the night itself caressing me. I went from there to the sun’s warm caresses on a late spring day. The embrace of the ocean or a lake or a stream. The support given to our daily walking by the surface of mother earth. The uplift we experience on Shadow Mountain, 8,800 feet above sea level. These are tactile realities, often felt (0r their equivalent). Next, eliminate the metaphorical. If we do that, we can immediately jump into a holy moment, a moment when the bonds that tie us to grandmother earth are not figurative, but real. The breeze on my bare arms and shoulders is her embrace. The sun on my face, penetrating my body, is him in direct relationship with me, reaching across 93 million miles, warming me. The ocean or the lake or the pond or the stream cools me, refreshes me, hydrates me, acts of chesed, loving-kindness, from the universe in which we live and move and have our being.

Next, eliminate the metaphorical. If we do that, we can immediately jump into a holy moment, a moment when the bonds that tie us to grandmother earth are not figurative, but real. The breeze on my bare arms and shoulders is her embrace. The sun on my face, penetrating my body, is him in direct relationship with me, reaching across 93 million miles, warming me. The ocean or the lake or the pond or the stream cools me, refreshes me, hydrates me, acts of chesed, loving-kindness, from the universe in which we live and move and have our being.

While hiking and thinking about Reimagining, I realized I’m taking an atelier approach to it. Ateliers train would be artists in the classical mode, using lots of drawing, life models and work with perspective. They’re considered conservative in today’s art world, a sort of throwback to the artist/apprentice studio that dominated art education for so many centuries.

While hiking and thinking about Reimagining, I realized I’m taking an atelier approach to it. Ateliers train would be artists in the classical mode, using lots of drawing, life models and work with perspective. They’re considered conservative in today’s art world, a sort of throwback to the artist/apprentice studio that dominated art education for so many centuries. Yet what I really want to do is rethink what faith is, why we go to the places that we go to for spiritual nourishment and whether there might be a real faith, an approach to the religious life, that emerges naturally from the world in which we live and carry on our daily lives. That is, one without a charismatic founder or an ethnic base, a faith which would help us see the holy ordinary, that would expose the ligatures that bind us to this planet, to the plants and animals and minerals and atmosphere, expose them and help us see them as the loving embrace that they are, not only as limits to our lives.

Yet what I really want to do is rethink what faith is, why we go to the places that we go to for spiritual nourishment and whether there might be a real faith, an approach to the religious life, that emerges naturally from the world in which we live and carry on our daily lives. That is, one without a charismatic founder or an ethnic base, a faith which would help us see the holy ordinary, that would expose the ligatures that bind us to this planet, to the plants and animals and minerals and atmosphere, expose them and help us see them as the loving embrace that they are, not only as limits to our lives. Another short trough of time where work here will focus on moving, rearranging, hanging.

Another short trough of time where work here will focus on moving, rearranging, hanging. But not yet. The next period of time belongs to another very long term project, reimagining faith. There is that bookshelf filled with works on emergence, of pagan thought, on holiness and sacred time, on the Great Wheel, on the enlightenment, on nature and wilderness. There are file folders to be collected from their various resting places and computer files, too. Printouts to be made of writing already done. Long walks to be taken, using shinrin-yoku to further this work. Drives to be taken in the Rocky Mountains, over to South Park, down to Durango, up again to the Neversummer Wilderness. The Rockies will influence reimagining in ways I don’t yet understand.

But not yet. The next period of time belongs to another very long term project, reimagining faith. There is that bookshelf filled with works on emergence, of pagan thought, on holiness and sacred time, on the Great Wheel, on the enlightenment, on nature and wilderness. There are file folders to be collected from their various resting places and computer files, too. Printouts to be made of writing already done. Long walks to be taken, using shinrin-yoku to further this work. Drives to be taken in the Rocky Mountains, over to South Park, down to Durango, up again to the Neversummer Wilderness. The Rockies will influence reimagining in ways I don’t yet understand. While the world burns, at least the Trump world, kabbalah suggests a bigger world, more worlds, right next to this one. There is, as Rabbi Jamie said, a bigger picture. I learned a similar lesson from Deer Creek Canyon during my cancer season two years ago. These Rocky Mountains, still toddlers as mountains go, were and will be present when we are not. In their lifetime humanity will likely have come and gone.

While the world burns, at least the Trump world, kabbalah suggests a bigger world, more worlds, right next to this one. There is, as Rabbi Jamie said, a bigger picture. I learned a similar lesson from Deer Creek Canyon during my cancer season two years ago. These Rocky Mountains, still toddlers as mountains go, were and will be present when we are not. In their lifetime humanity will likely have come and gone. Yet. We do not live either in the deep geological past nor in the distant geological future, we live now. Our lives, our mayfly lives from the vantage point of geological time, come into existence and blink out, so we necessarily look at the moment, the brief seventy to one hundred year moment into which, as Heidegger said, we are thrown.

Yet. We do not live either in the deep geological past nor in the distant geological future, we live now. Our lives, our mayfly lives from the vantage point of geological time, come into existence and blink out, so we necessarily look at the moment, the brief seventy to one hundred year moment into which, as Heidegger said, we are thrown. Somehow we have to realize that though our lives are small compared to the immensity of the universe and the imponderable nature of time, they are everything while we have them. As for me, I find all this comforting. Putting my efforts in the larger perspective gives me peace, putting them in the immediacy of my life gives me energy. We will not complete the task, no, we will not. But we are not free to give it up either.

Somehow we have to realize that though our lives are small compared to the immensity of the universe and the imponderable nature of time, they are everything while we have them. As for me, I find all this comforting. Putting my efforts in the larger perspective gives me peace, putting them in the immediacy of my life gives me energy. We will not complete the task, no, we will not. But we are not free to give it up either.