Midsommar Most Heat Moon

The dog days. Maybe not yet as hot as this mosaic portrays, certainly not here on Shadow Mountain, though Tucson and Phoenix… Friend Tom Crane sent me a link to this Updraft post about the dog days. I miss having an erudite blog like Updraft keeping me alert about weather. Weather5280 is the closest I’ve found. It’s good on weather, but it doesn’t go off into sidebars like explaining the days after the heliacal rising of Sirius. Heliacal? What’s that you might ask? Turns out heliacal is the first appearance of a star after a long absence. The dog days begin with the return of the brightest star in the night sky, Sirius. Or, at least they used to.

The Romans believed that the dog days were so hot that they made dog’s rabid. Sirius is the major star in the constellation, Canis Major, the Great Dog, but the Romans didn’t originate linking the rising of Sirius with heat. That belongs to the Greeks. They named the star “Seirios, Greek for “sparking” (referring to its near-constant twinkling), “fiery,” or “scorching,”” According to this page on Sky and Telescope, the Greeks believed its -1.46 magnitude intensified the already hot days of a Mediterranean summer.

Neither the Greeks nor the Romans, however, were the first ancient civilization to highlight the dog star. The Egyptians began the New Year when Sirius returned to the night sky because it corresponded with the flooding of the Nile, a seasonal nourishing of the fields that made Egyptian civilization flourish. Their calendar though, because it lacked the leap year, gradually moved the month of the new year further and further from Sirius’s heliacal rise.

This lead to a discovery of the Sothic year, 1461 years of ancient Egypt’s 365 day year or 1460 of the Julian sidereal year which adds leap years. A Sothic year follows the gradual movement of the New Year until it once again occurs when the Nile floods, synching up with Sirius’s heliacal moment.

In spite of my long established affection for Orion, or perhaps because of it, I’ve never focused on Sirius. That’s a bit surprising since Canis Major is Orion’s hunting dog and Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. I’ll be looking for it as rises this year here on Shadow Mountain, probably August 10th.

When I see it, I’ll think of this from the Sky and Telescope article because it reflects my own wistfulness for a reenchanted world:

“While the first sighting of Sirius may not signify anything as momentous as the annual flooding of the Nile, seeing it tenderly twinkling at dawn can take us back in time to when it was commonplace for people to use stars to mark important events in their lives. How far we’ve strayed.”

Next week we all give 5-8 minute presentations in our kabbalah class. The ostensible purpose is for us to have the chance to “learn as teachers.” It will be more than that for me. At first I thought I would work up something about tikkun olam, repairing the world, or, as the early kabbalists preferred, repairing God. The notion fits nicely within my political activism (now shelved)/reimagining faith work. But that would have been the more traditional student as presenter, a small talk focused on the content of what I’ve begun to learn.

Next week we all give 5-8 minute presentations in our kabbalah class. The ostensible purpose is for us to have the chance to “learn as teachers.” It will be more than that for me. At first I thought I would work up something about tikkun olam, repairing the world, or, as the early kabbalists preferred, repairing God. The notion fits nicely within my political activism (now shelved)/reimagining faith work. But that would have been the more traditional student as presenter, a small talk focused on the content of what I’ve begun to learn. Kabbalah has reinforced and challenged a move I made many years ago away from the metaphysics of the Judaeo-Christian tradition as I understood it. I can summarize that move as a reaction against transcendence and its role in buttressing patriarchy. Transcendence moved me up and out of my body, up and out of my Self into a different a place, a place other than where I was, a better place, a place dominated by God. It didn’t really matter what image of God, what understanding of God you put in that sentence because it was the denial of the here and now, the embodiedness of us, that bothered me. The notion that transcendence puts us in a better place, a place only accessible outside of our bodies made us lesser creatures, doomed to spend most of our time in a less spiritual state. In the long tradition of a male imaged God it made that gender dominate because it was God that occupied the better place, the more spiritual place, the place, if we were lucky or faithful enough, that we might achieve permanently after death.

Kabbalah has reinforced and challenged a move I made many years ago away from the metaphysics of the Judaeo-Christian tradition as I understood it. I can summarize that move as a reaction against transcendence and its role in buttressing patriarchy. Transcendence moved me up and out of my body, up and out of my Self into a different a place, a place other than where I was, a better place, a place dominated by God. It didn’t really matter what image of God, what understanding of God you put in that sentence because it was the denial of the here and now, the embodiedness of us, that bothered me. The notion that transcendence puts us in a better place, a place only accessible outside of our bodies made us lesser creatures, doomed to spend most of our time in a less spiritual state. In the long tradition of a male imaged God it made that gender dominate because it was God that occupied the better place, the more spiritual place, the place, if we were lucky or faithful enough, that we might achieve permanently after death. This inner turn is what pagan means for me. It put spirituality more in the mode the Judaeo-Christian tradition terms incarnation, put a thumb on the scale for the notion of imago dei, rather than the three-story universe. Gardening and bee-keeping became ultimate spiritual practices. They made real, as real as can be, the whole immersion of this body in the web of life. Tomatoes, beets, leeks, garlic, raspberries, plums, apples, currants, beans, comb honey and liquid honey grew on our land, nurtured by our hands, then entered our bodies to actually, really become us. The true transubstantiation.

This inner turn is what pagan means for me. It put spirituality more in the mode the Judaeo-Christian tradition terms incarnation, put a thumb on the scale for the notion of imago dei, rather than the three-story universe. Gardening and bee-keeping became ultimate spiritual practices. They made real, as real as can be, the whole immersion of this body in the web of life. Tomatoes, beets, leeks, garlic, raspberries, plums, apples, currants, beans, comb honey and liquid honey grew on our land, nurtured by our hands, then entered our bodies to actually, really become us. The true transubstantiation.

When I moved away from transcendence, I moved toward this world. This world of sensation and my inner world became the whole, I sheared off the metaphysical almost as cleanly as my logical positivist philosophy had done, though for quite different reasons. No metaphysics, no God. No metaphysics, no transcendence. I switched to an ontology informed only by my senses or by the extended reach of our limited human senses occasioned by science. That meant this world, at both the micro and macro levels was the only world.

When I moved away from transcendence, I moved toward this world. This world of sensation and my inner world became the whole, I sheared off the metaphysical almost as cleanly as my logical positivist philosophy had done, though for quite different reasons. No metaphysics, no God. No metaphysics, no transcendence. I switched to an ontology informed only by my senses or by the extended reach of our limited human senses occasioned by science. That meant this world, at both the micro and macro levels was the only world. Kabbalah. It’s trying to pry off the empiricist covering I’ve put on my world. I say trying because I’m a skeptic at heart, a doubter, a critic, an analyst yet also, and just as deeply, a poet, a lover of myth and fantasy, a dreamer.

Kabbalah. It’s trying to pry off the empiricist covering I’ve put on my world. I say trying because I’m a skeptic at heart, a doubter, a critic, an analyst yet also, and just as deeply, a poet, a lover of myth and fantasy, a dreamer. Rabbi Akiva says that nothing in nature is less miraculous than the rarest exception. This means, for example, that the water in the Red Sea (or, Reed Sea) is as miraculous as its parting. Or, for that matter, the Hebrew slaves pouring across it are, too.

Rabbi Akiva says that nothing in nature is less miraculous than the rarest exception. This means, for example, that the water in the Red Sea (or, Reed Sea) is as miraculous as its parting. Or, for that matter, the Hebrew slaves pouring across it are, too. It is anxiety. I believe it infested my life in two early stages. The first was polio, a young boy’s physical experience of our human finitude. It happened once; it could happen again. The second was the death of my mother when I was 17. It happened once, to Mom. It will happen to me and could happen quickly.

It is anxiety. I believe it infested my life in two early stages. The first was polio, a young boy’s physical experience of our human finitude. It happened once; it could happen again. The second was the death of my mother when I was 17. It happened once, to Mom. It will happen to me and could happen quickly. The wrong part is that it doesn’t matter. I don’t have to worry about it, fear it, be anxious about it. It is. Or, rather, will be. Maybe in the next ten minutes, maybe in the next ten years, maybe longer. I know this by reason, have known it for a long, long time, but I have not been able to displace the irrational fear in spite of that knowledge. That’s why I say reason can take me up to the wall, but not past it.

The wrong part is that it doesn’t matter. I don’t have to worry about it, fear it, be anxious about it. It is. Or, rather, will be. Maybe in the next ten minutes, maybe in the next ten years, maybe longer. I know this by reason, have known it for a long, long time, but I have not been able to displace the irrational fear in spite of that knowledge. That’s why I say reason can take me up to the wall, but not past it. Yet, increasingly I find myself wanting a way through this. I can sense, and here kabbalah is playing a critical alchemical role, a different world, a better world now hidden from me. I can peek through the vines at times, can see the secret garden beyond. It’s this wall that holds up the substrata, keeps it from being ground other parts of my Self. This wall has its roots sunk deep into this tectonic plate, is a barrier to its movement. But I can feel the vines withering, their complicity in the substrata’s effect on my psyche weakening.

Yet, increasingly I find myself wanting a way through this. I can sense, and here kabbalah is playing a critical alchemical role, a different world, a better world now hidden from me. I can peek through the vines at times, can see the secret garden beyond. It’s this wall that holds up the substrata, keeps it from being ground other parts of my Self. This wall has its roots sunk deep into this tectonic plate, is a barrier to its movement. But I can feel the vines withering, their complicity in the substrata’s effect on my psyche weakening. After leaving the ministry, a gradual process of demythologization and disenchantment took over. In retrospect it’s not hard to see why. A primary motivator of the shift away from Christianity and toward a more pagan worldview came because transcendence bothered me. Transcendence takes us up and out of our bodies, or least out and away from our bodies.

After leaving the ministry, a gradual process of demythologization and disenchantment took over. In retrospect it’s not hard to see why. A primary motivator of the shift away from Christianity and toward a more pagan worldview came because transcendence bothered me. Transcendence takes us up and out of our bodies, or least out and away from our bodies. Then, at some point-the reimagining faith project signals that point-the flat-earth humanism of this pagan orientation no longer felt like enough. Could the warmth and the depth available to those in the ancient religious traditions somehow be suffused into this empiricist, anti-metaphysical worldview? Could, in other words, a feeling of religious awe and wonder emerge out of our relationship with the web of life and the cosmic experiment we know as the universe?

Then, at some point-the reimagining faith project signals that point-the flat-earth humanism of this pagan orientation no longer felt like enough. Could the warmth and the depth available to those in the ancient religious traditions somehow be suffused into this empiricist, anti-metaphysical worldview? Could, in other words, a feeling of religious awe and wonder emerge out of our relationship with the web of life and the cosmic experiment we know as the universe? Transcendence still seems suspect. Reimagining though has to take account of it in some way. Here’s one idea. The mystical experience, a well documented and not at all rare phenomenon, often carries the descriptor transcendent. I had one and I want to challenge that idea. In mine, which occurred in 1967 on the quad at Ball State University, I did feel a sudden and inexplicable connection to the universe, all of it. Threads of light and power emanated in a pulsing glory carrying with them a physical sensation of oneness.

Transcendence still seems suspect. Reimagining though has to take account of it in some way. Here’s one idea. The mystical experience, a well documented and not at all rare phenomenon, often carries the descriptor transcendent. I had one and I want to challenge that idea. In mine, which occurred in 1967 on the quad at Ball State University, I did feel a sudden and inexplicable connection to the universe, all of it. Threads of light and power emanated in a pulsing glory carrying with them a physical sensation of oneness. Yet again, I didn’t follow this one completely, but the Lurianic God is a God in exile, separated from the shards. So when the Jews go into exile, they do so as one with their estranged God. The purpose of the Jews is to remind humanity of this estrangement and that we all have a role to play in overcoming it.

Yet again, I didn’t follow this one completely, but the Lurianic God is a God in exile, separated from the shards. So when the Jews go into exile, they do so as one with their estranged God. The purpose of the Jews is to remind humanity of this estrangement and that we all have a role to play in overcoming it. Looking for light in prison. An assignment for the kabbalah class tonight. Rabbi Jamie suggested watching a movie like Hurricane, about Rubin Carter. I thought of MLK and Letters from the Birmingham Jail and Nelson Mandela, too. Then I remembered a portion of the

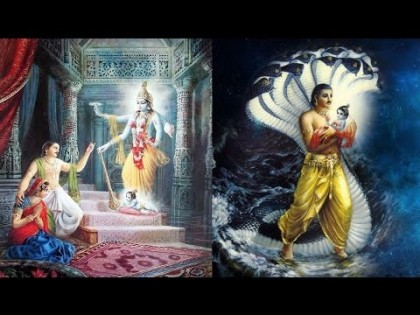

Looking for light in prison. An assignment for the kabbalah class tonight. Rabbi Jamie suggested watching a movie like Hurricane, about Rubin Carter. I thought of MLK and Letters from the Birmingham Jail and Nelson Mandela, too. Then I remembered a portion of the  Finally, nine years later, Devaki is pregnant again, this time with the eighth son Kansa dreaded. This son is Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu.

Finally, nine years later, Devaki is pregnant again, this time with the eighth son Kansa dreaded. This son is Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu.

It’s a very bright group around the table: a historian, a Berkeley trained lawyer, an organizational consultant, a Hebrew scholar, a rabbi in training, a second lawyer, a teenager with a good grasp of theoretical physics, two retired hospital administrators. This makes the conversation sparky, inspirational.

It’s a very bright group around the table: a historian, a Berkeley trained lawyer, an organizational consultant, a Hebrew scholar, a rabbi in training, a second lawyer, a teenager with a good grasp of theoretical physics, two retired hospital administrators. This makes the conversation sparky, inspirational.

The shift to Reimagining has happened faster than I thought it would. My mind is like Kepler, our only dog who likes toys. He has a whole box of toys and he goes into it, noses around, finds the one he likes (why that one? no idea.), takes it out and carries it over to a place he’s decided is his toy stash area. I have several ideas that I’ve been playing with for years, e.g. becoming native to this place, emergence, tactile spirituality. In ways I don’t understand my mind goes over to the box of these ideas, hunts around, selects one and puts it front and center for maybe a second, maybe longer. Sometimes I pick up and play with one for awhile.

The shift to Reimagining has happened faster than I thought it would. My mind is like Kepler, our only dog who likes toys. He has a whole box of toys and he goes into it, noses around, finds the one he likes (why that one? no idea.), takes it out and carries it over to a place he’s decided is his toy stash area. I have several ideas that I’ve been playing with for years, e.g. becoming native to this place, emergence, tactile spirituality. In ways I don’t understand my mind goes over to the box of these ideas, hunts around, selects one and puts it front and center for maybe a second, maybe longer. Sometimes I pick up and play with one for awhile. In the shower one day I began to wonder where our water came from. At the time Kate and I lived on Edgcumbe Avenue in St. Paul so the question really was, where did St. Paul get its water? I had no idea. Turns out St. Paul public works pumps water out of the Mississippi and into a chain of lakes including Pleasant Lake and Sucker Lake just across the Anoka County border in Ramsey County north of St. Paul.

In the shower one day I began to wonder where our water came from. At the time Kate and I lived on Edgcumbe Avenue in St. Paul so the question really was, where did St. Paul get its water? I had no idea. Turns out St. Paul public works pumps water out of the Mississippi and into a chain of lakes including Pleasant Lake and Sucker Lake just across the Anoka County border in Ramsey County north of St. Paul. Though I haven’t done it, it would be possible to track back much further to the arrival of water on earth. This is a very interesting topic which I raise only to demonstrate the potential in this kind of thinking.

Though I haven’t done it, it would be possible to track back much further to the arrival of water on earth. This is a very interesting topic which I raise only to demonstrate the potential in this kind of thinking. Open the refrigerator. Where did the food come from? How about the carpet on your floor? The roofing material. Concrete. Paint. How about the car in your garage? Where was it built? What sort of materials go into making it? Where do they come from?

Open the refrigerator. Where did the food come from? How about the carpet on your floor? The roofing material. Concrete. Paint. How about the car in your garage? Where was it built? What sort of materials go into making it? Where do they come from? The incredible complexity of this web has put a thick wall between our daily lives and the earthiness of all that is around us. We start the car, shift into drive and head out to work or the store or on vacation dulled to the effort expended on the gasoline that fuels it, the rubber in the tires, the precious metals and the not-so precious metals in the body and frame and engine. I’m not talking right now about a car’s implication in climate change, or economic injustice, or urban planning. I’m focusing on getting to know how it came to be, what of our world made it possible.

The incredible complexity of this web has put a thick wall between our daily lives and the earthiness of all that is around us. We start the car, shift into drive and head out to work or the store or on vacation dulled to the effort expended on the gasoline that fuels it, the rubber in the tires, the precious metals and the not-so precious metals in the body and frame and engine. I’m not talking right now about a car’s implication in climate change, or economic injustice, or urban planning. I’m focusing on getting to know how it came to be, what of our world made it possible. Why? Because focusing on these things, deconstructing our things, begins to break the spell of modernism. Modernism offers us in the developed world a world prepackaged for our needs, organized so that we don’t have to till the field anymore, or hitch up the horse, or drop a bucket down a well. In so doing it waves the wand of mystification over our senses, blinding us to the mines, the aquifers, the oil fields, the vegetable fields, the landfills, the seeds and chemicals required to sustain us. This enchantment is the first barrier to a reimagined faith, to placing ourselves once again in the world.

Why? Because focusing on these things, deconstructing our things, begins to break the spell of modernism. Modernism offers us in the developed world a world prepackaged for our needs, organized so that we don’t have to till the field anymore, or hitch up the horse, or drop a bucket down a well. In so doing it waves the wand of mystification over our senses, blinding us to the mines, the aquifers, the oil fields, the vegetable fields, the landfills, the seeds and chemicals required to sustain us. This enchantment is the first barrier to a reimagined faith, to placing ourselves once again in the world. With the first draft of Superior Wolf finished I’m taking this week to do various tasks up in the loft that I’ve deferred. Gonna hang some art, rearrange some (by categories like Latin American, contemporary, Asian) and bring order to some of my disorganized book shelves. I want to get some outside work in, too, maybe get back to limbing and do some stump cutting, check out nurseries for lilac bushes.

With the first draft of Superior Wolf finished I’m taking this week to do various tasks up in the loft that I’ve deferred. Gonna hang some art, rearrange some (by categories like Latin American, contemporary, Asian) and bring order to some of my disorganized book shelves. I want to get some outside work in, too, maybe get back to limbing and do some stump cutting, check out nurseries for lilac bushes. Even so, reimagining is beginning to exert a centripetal force on my thinking, book purchasing, day to day. For example, last night as I went to sleep a cool breeze blew in from the north across my bare arms and shoulder. It was the night itself caressing me. I went from there to the sun’s warm caresses on a late spring day. The embrace of the ocean or a lake or a stream. The support given to our daily walking by the surface of mother earth. The uplift we experience on Shadow Mountain, 8,800 feet above sea level. These are tactile realities, often felt (0r their equivalent).

Even so, reimagining is beginning to exert a centripetal force on my thinking, book purchasing, day to day. For example, last night as I went to sleep a cool breeze blew in from the north across my bare arms and shoulder. It was the night itself caressing me. I went from there to the sun’s warm caresses on a late spring day. The embrace of the ocean or a lake or a stream. The support given to our daily walking by the surface of mother earth. The uplift we experience on Shadow Mountain, 8,800 feet above sea level. These are tactile realities, often felt (0r their equivalent). Next, eliminate the metaphorical. If we do that, we can immediately jump into a holy moment, a moment when the bonds that tie us to grandmother earth are not figurative, but real. The breeze on my bare arms and shoulders is her embrace. The sun on my face, penetrating my body, is him in direct relationship with me, reaching across 93 million miles, warming me. The ocean or the lake or the pond or the stream cools me, refreshes me, hydrates me, acts of chesed, loving-kindness, from the universe in which we live and move and have our being.

Next, eliminate the metaphorical. If we do that, we can immediately jump into a holy moment, a moment when the bonds that tie us to grandmother earth are not figurative, but real. The breeze on my bare arms and shoulders is her embrace. The sun on my face, penetrating my body, is him in direct relationship with me, reaching across 93 million miles, warming me. The ocean or the lake or the pond or the stream cools me, refreshes me, hydrates me, acts of chesed, loving-kindness, from the universe in which we live and move and have our being.