Lughnasa Eclipse Moon

Say awe. My focus phrase for this month’s middot: yirah, or awe. (middot=character trait)

Albert Camus. One of my favorite theologians. It occurred to me that the abyss Camus mentions may be what gets crossed when we experience awe. Somehow we let the absurd in, or the mute world gives us a shout.

Albert Camus. One of my favorite theologians. It occurred to me that the abyss Camus mentions may be what gets crossed when we experience awe. Somehow we let the absurd in, or the mute world gives us a shout.

“For Camus … [our] astonishment [at life] results from our confrontation with a world that refuses to surrender meaning. It occurs when our need for meaning shatters against the indifference, immovable and absolute, of the world. As a result, absurdity is not an autonomous state; it does not exist in the world, but is instead exhaled from the abyss that divides us from a mute world. ‘This world in itself is not reasonable, that is all that can be said. But what is absurd is the confrontation of this irrational and wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart. The absurd depends as much on man as on the world. For the moment it is all that links them together.’ …”

Here’s another way of thinking about awe from Alan Morinis, a mussar guru:

“Awe is the feeling of being overwhelmed by a reality greater than yourself and greater than what you encounter in ordinary life. A curtain is drawn back and the little human is overtaken by a trembling awareness that life is astounding in its reality, vastness, complexity, order, surprise. Experiences of awe awaken a spiritual awareness.”

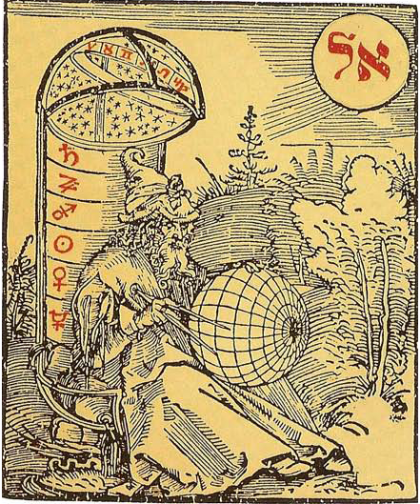

Immanuel Kant used the phrase ding an sich, the thing-in-itself, to name that from which our senses separate us. We experience the ding an sich, the mute world of Camus, only through our senses, through our sensory experience of certain qualities, qualia, that the thing-in-itself presents. We do not, in other words, experience that which has the qualities, but only its qualia and then only those within the very limited range of qualia accessible to our senses.

The ding an sich, the abyss, a reality greater than yourself all name a something beyond ordinary experience. There are many ways of articulating the gap between us and the ding an sich, the things in themselves.

Here’s one I like. Bifrost is the rainbow bridge of Norse mythology. As in this illustration, bifrost connects Asgard, the realm of the Aesir (Odin, Thor, Freya), and midgard, or middle earth, the realm of humans. Awe could be a brief moment when we stand not on midgard but on the rainbow bridge, able to catch a glimpse of the realm beyond us.

Or, we might consider the Hindu concept of maya. Among other meanings maya is a “magic show, an illusion where things appear to be present but are not what they seem”” wikipedia

What all of these ideas suggest, I think, is that a gap exists between an individual and the really real. An important religious question is what is beyond that gap, or what constitutes the gap, or what is the significance of the hidden for our spiritual lives.

What all of these ideas suggest, I think, is that a gap exists between an individual and the really real. An important religious question is what is beyond that gap, or what constitutes the gap, or what is the significance of the hidden for our spiritual lives.

I don’t know how to answer that question. Camus’ notion of the absurd makes sense to me. If that’s not an oxymoron. What I do know, for sure, is that the only tool we have for answering it is our experience. Awe may help us. It may allow us a momentary peek into the abyss, or place us on bifrost, or pierce the veil of maya.

What has awed you this day? This week? This year? In this life?

Took off yesterday morning about 7:30 am and drove west (or south) on Hwy 285 headed toward Park County, Bailey and Fairplay. I stopped at Grant, a place made visible only by its single, as near as I can tell, business, the Shaggy Sheep. There’s one of those yellow diamond signs just after it with a black silhouette of a bighorn sheep. This is one of several instances of displaced chefs seeking less frenetic lifestyles in the mountains. I mentioned the Badger Creek Cafe in Tetonia, Idaho in my eclipse post. There are others.

Took off yesterday morning about 7:30 am and drove west (or south) on Hwy 285 headed toward Park County, Bailey and Fairplay. I stopped at Grant, a place made visible only by its single, as near as I can tell, business, the Shaggy Sheep. There’s one of those yellow diamond signs just after it with a black silhouette of a bighorn sheep. This is one of several instances of displaced chefs seeking less frenetic lifestyles in the mountains. I mentioned the Badger Creek Cafe in Tetonia, Idaho in my eclipse post. There are others.

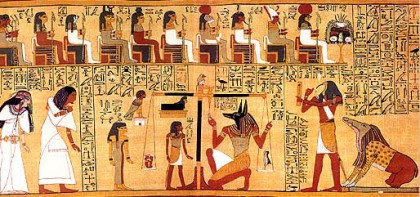

Moving forward, slowly, with Jennie’s Dead. Exploring the religion of the ancient Egyptians, trying to avoid hackneyed themes, not easy with all the mummy movies, Scorpion King, Raiders of the Lost Ark sort of cinema. Jennie’s Dead is not about Egypt, ancient or otherwise, but it plays an important role in the plot. Getting started is difficult, trying to sort out where the story wants to go, whether the main conflict is clear, to me and to the eventual reader.

Moving forward, slowly, with Jennie’s Dead. Exploring the religion of the ancient Egyptians, trying to avoid hackneyed themes, not easy with all the mummy movies, Scorpion King, Raiders of the Lost Ark sort of cinema. Jennie’s Dead is not about Egypt, ancient or otherwise, but it plays an important role in the plot. Getting started is difficult, trying to sort out where the story wants to go, whether the main conflict is clear, to me and to the eventual reader. As Emerson said, “Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? Why should not we also enjoy

As Emerson said, “Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? Why should not we also enjoy  This means I’m in a curious position relevant to my own education in the Christian tradition and my new education, underway now, in the older faith tradition of Judaism. Both are normative, in their way, but not as holy writ. Rather, they are normative in a more fundamental sense, they reveal the way we humans can discover the sacred as it wends and winds its way not only through the universe, but through history.

This means I’m in a curious position relevant to my own education in the Christian tradition and my new education, underway now, in the older faith tradition of Judaism. Both are normative, in their way, but not as holy writ. Rather, they are normative in a more fundamental sense, they reveal the way we humans can discover the sacred as it wends and winds its way not only through the universe, but through history. This is a similar idea to that of the reconstructionists, but not the same. Reconstructionists want to work with a constantly evolving Jewish civilization, grounding themselves in Torah, mussar, kabbalah, shabbat, the old holidays, but emphasizing the work of building a Jewish culture in the current day, reconstructing it as Jews change and the world around them changes, too. I’m learning so much from this radical idea.

This is a similar idea to that of the reconstructionists, but not the same. Reconstructionists want to work with a constantly evolving Jewish civilization, grounding themselves in Torah, mussar, kabbalah, shabbat, the old holidays, but emphasizing the work of building a Jewish culture in the current day, reconstructing it as Jews change and the world around them changes, too. I’m learning so much from this radical idea. What I want to do though, and it’s a similar challenge, is to reimagine, for our time and as a dynamic, the way we reach for the sacred, the way we write about our experience, the way we celebrate the insights and the poetry it inspires. In this Reconstructionist Judaism is a better home for me than Unitarian Universalism. UU’s may have the same goal, but their net is cast into the vague sea of the past, trying to catch a bit from here and a bit from there. It is untethered, floating with no anchor. Beth Evergreen affirms the past, the texts of their ancestors, their thousands of years of interpretation, the holidays and the personal, daily life of a person shaped by this tradition, but also recognizes the need to live those insights in an evolving world.

What I want to do though, and it’s a similar challenge, is to reimagine, for our time and as a dynamic, the way we reach for the sacred, the way we write about our experience, the way we celebrate the insights and the poetry it inspires. In this Reconstructionist Judaism is a better home for me than Unitarian Universalism. UU’s may have the same goal, but their net is cast into the vague sea of the past, trying to catch a bit from here and a bit from there. It is untethered, floating with no anchor. Beth Evergreen affirms the past, the texts of their ancestors, their thousands of years of interpretation, the holidays and the personal, daily life of a person shaped by this tradition, but also recognizes the need to live those insights in an evolving world. It’s been a rainy, cold week here on Shadow Mountain. The dial on the various fire risk signs is either on low or moderate. Gotta love the monsoons. Yesterday we came home from Beth Evergreen and it was 71 in Evergreen, 60 at the house. Not very far mileage wise from Evergreen, but the altitude really makes a difference.

It’s been a rainy, cold week here on Shadow Mountain. The dial on the various fire risk signs is either on low or moderate. Gotta love the monsoons. Yesterday we came home from Beth Evergreen and it was 71 in Evergreen, 60 at the house. Not very far mileage wise from Evergreen, but the altitude really makes a difference. Ruth and I are going to the Fiske Planetarium tomorrow for a show on the moon. Kate will go along, as will Gabe. That way Jon can have time to work on the bench in the dining room. I’ll have a chance to stop at the

Ruth and I are going to the Fiske Planetarium tomorrow for a show on the moon. Kate will go along, as will Gabe. That way Jon can have time to work on the bench in the dining room. I’ll have a chance to stop at the  Oh. Right. Slept in yesterday until 7:30 am. About 2.5 hours past normal rising. The guy from Conifer Gutter came by to give us an estimate on needle guards for our gutters. Then, well, I worked out and forgot to post.

Oh. Right. Slept in yesterday until 7:30 am. About 2.5 hours past normal rising. The guy from Conifer Gutter came by to give us an estimate on needle guards for our gutters. Then, well, I worked out and forgot to post.

This evening is the last of the introductory kabbalah classes. We’ll be discussing miracles again and hearing student presentations. Making it personal still seems like the right path for mine, how kabbalah has affected a decades long journey, a pilgrimage toward the world into which I’ve been thrown.

This evening is the last of the introductory kabbalah classes. We’ll be discussing miracles again and hearing student presentations. Making it personal still seems like the right path for mine, how kabbalah has affected a decades long journey, a pilgrimage toward the world into which I’ve been thrown. Here’s a nice paragraph: “While the hermeneutic strategies to “open up the text” that Ricoeur presents are not simple or childlike, they’re only the first step in engaging with the ideas. If you understand “the meek shall inherit the earth” as a radical idea, what do you do with that? How do you apply it? How do you let it change you? Following

Here’s a nice paragraph: “While the hermeneutic strategies to “open up the text” that Ricoeur presents are not simple or childlike, they’re only the first step in engaging with the ideas. If you understand “the meek shall inherit the earth” as a radical idea, what do you do with that? How do you apply it? How do you let it change you? Following  The biggest change will be in how I sense the world around me. I will no longer be so reductive, imagining that even if there is an unseen world, that’s all it is, unseen. Perhaps this is how the reenchantment process works, seeing the living, intricately woven cosmos as manifest everywhere, visibly and invisibly. My pagan sensibility remains. I’m not sure that adding God language to the mix adds anything important.

The biggest change will be in how I sense the world around me. I will no longer be so reductive, imagining that even if there is an unseen world, that’s all it is, unseen. Perhaps this is how the reenchantment process works, seeing the living, intricately woven cosmos as manifest everywhere, visibly and invisibly. My pagan sensibility remains. I’m not sure that adding God language to the mix adds anything important.

Next week we all give 5-8 minute presentations in our kabbalah class. The ostensible purpose is for us to have the chance to “learn as teachers.” It will be more than that for me. At first I thought I would work up something about tikkun olam, repairing the world, or, as the early kabbalists preferred, repairing God. The notion fits nicely within my political activism (now shelved)/reimagining faith work. But that would have been the more traditional student as presenter, a small talk focused on the content of what I’ve begun to learn.

Next week we all give 5-8 minute presentations in our kabbalah class. The ostensible purpose is for us to have the chance to “learn as teachers.” It will be more than that for me. At first I thought I would work up something about tikkun olam, repairing the world, or, as the early kabbalists preferred, repairing God. The notion fits nicely within my political activism (now shelved)/reimagining faith work. But that would have been the more traditional student as presenter, a small talk focused on the content of what I’ve begun to learn. Kabbalah has reinforced and challenged a move I made many years ago away from the metaphysics of the Judaeo-Christian tradition as I understood it. I can summarize that move as a reaction against transcendence and its role in buttressing patriarchy. Transcendence moved me up and out of my body, up and out of my Self into a different a place, a place other than where I was, a better place, a place dominated by God. It didn’t really matter what image of God, what understanding of God you put in that sentence because it was the denial of the here and now, the embodiedness of us, that bothered me. The notion that transcendence puts us in a better place, a place only accessible outside of our bodies made us lesser creatures, doomed to spend most of our time in a less spiritual state. In the long tradition of a male imaged God it made that gender dominate because it was God that occupied the better place, the more spiritual place, the place, if we were lucky or faithful enough, that we might achieve permanently after death.

Kabbalah has reinforced and challenged a move I made many years ago away from the metaphysics of the Judaeo-Christian tradition as I understood it. I can summarize that move as a reaction against transcendence and its role in buttressing patriarchy. Transcendence moved me up and out of my body, up and out of my Self into a different a place, a place other than where I was, a better place, a place dominated by God. It didn’t really matter what image of God, what understanding of God you put in that sentence because it was the denial of the here and now, the embodiedness of us, that bothered me. The notion that transcendence puts us in a better place, a place only accessible outside of our bodies made us lesser creatures, doomed to spend most of our time in a less spiritual state. In the long tradition of a male imaged God it made that gender dominate because it was God that occupied the better place, the more spiritual place, the place, if we were lucky or faithful enough, that we might achieve permanently after death. This inner turn is what pagan means for me. It put spirituality more in the mode the Judaeo-Christian tradition terms incarnation, put a thumb on the scale for the notion of imago dei, rather than the three-story universe. Gardening and bee-keeping became ultimate spiritual practices. They made real, as real as can be, the whole immersion of this body in the web of life. Tomatoes, beets, leeks, garlic, raspberries, plums, apples, currants, beans, comb honey and liquid honey grew on our land, nurtured by our hands, then entered our bodies to actually, really become us. The true transubstantiation.

This inner turn is what pagan means for me. It put spirituality more in the mode the Judaeo-Christian tradition terms incarnation, put a thumb on the scale for the notion of imago dei, rather than the three-story universe. Gardening and bee-keeping became ultimate spiritual practices. They made real, as real as can be, the whole immersion of this body in the web of life. Tomatoes, beets, leeks, garlic, raspberries, plums, apples, currants, beans, comb honey and liquid honey grew on our land, nurtured by our hands, then entered our bodies to actually, really become us. The true transubstantiation.

When I moved away from transcendence, I moved toward this world. This world of sensation and my inner world became the whole, I sheared off the metaphysical almost as cleanly as my logical positivist philosophy had done, though for quite different reasons. No metaphysics, no God. No metaphysics, no transcendence. I switched to an ontology informed only by my senses or by the extended reach of our limited human senses occasioned by science. That meant this world, at both the micro and macro levels was the only world.

When I moved away from transcendence, I moved toward this world. This world of sensation and my inner world became the whole, I sheared off the metaphysical almost as cleanly as my logical positivist philosophy had done, though for quite different reasons. No metaphysics, no God. No metaphysics, no transcendence. I switched to an ontology informed only by my senses or by the extended reach of our limited human senses occasioned by science. That meant this world, at both the micro and macro levels was the only world. Kabbalah. It’s trying to pry off the empiricist covering I’ve put on my world. I say trying because I’m a skeptic at heart, a doubter, a critic, an analyst yet also, and just as deeply, a poet, a lover of myth and fantasy, a dreamer.

Kabbalah. It’s trying to pry off the empiricist covering I’ve put on my world. I say trying because I’m a skeptic at heart, a doubter, a critic, an analyst yet also, and just as deeply, a poet, a lover of myth and fantasy, a dreamer. Rabbi Akiva says that nothing in nature is less miraculous than the rarest exception. This means, for example, that the water in the Red Sea (or, Reed Sea) is as miraculous as its parting. Or, for that matter, the Hebrew slaves pouring across it are, too.

Rabbi Akiva says that nothing in nature is less miraculous than the rarest exception. This means, for example, that the water in the Red Sea (or, Reed Sea) is as miraculous as its parting. Or, for that matter, the Hebrew slaves pouring across it are, too. It is anxiety. I believe it infested my life in two early stages. The first was polio, a young boy’s physical experience of our human finitude. It happened once; it could happen again. The second was the death of my mother when I was 17. It happened once, to Mom. It will happen to me and could happen quickly.

It is anxiety. I believe it infested my life in two early stages. The first was polio, a young boy’s physical experience of our human finitude. It happened once; it could happen again. The second was the death of my mother when I was 17. It happened once, to Mom. It will happen to me and could happen quickly. The wrong part is that it doesn’t matter. I don’t have to worry about it, fear it, be anxious about it. It is. Or, rather, will be. Maybe in the next ten minutes, maybe in the next ten years, maybe longer. I know this by reason, have known it for a long, long time, but I have not been able to displace the irrational fear in spite of that knowledge. That’s why I say reason can take me up to the wall, but not past it.

The wrong part is that it doesn’t matter. I don’t have to worry about it, fear it, be anxious about it. It is. Or, rather, will be. Maybe in the next ten minutes, maybe in the next ten years, maybe longer. I know this by reason, have known it for a long, long time, but I have not been able to displace the irrational fear in spite of that knowledge. That’s why I say reason can take me up to the wall, but not past it. Yet, increasingly I find myself wanting a way through this. I can sense, and here kabbalah is playing a critical alchemical role, a different world, a better world now hidden from me. I can peek through the vines at times, can see the secret garden beyond. It’s this wall that holds up the substrata, keeps it from being ground other parts of my Self. This wall has its roots sunk deep into this tectonic plate, is a barrier to its movement. But I can feel the vines withering, their complicity in the substrata’s effect on my psyche weakening.

Yet, increasingly I find myself wanting a way through this. I can sense, and here kabbalah is playing a critical alchemical role, a different world, a better world now hidden from me. I can peek through the vines at times, can see the secret garden beyond. It’s this wall that holds up the substrata, keeps it from being ground other parts of my Self. This wall has its roots sunk deep into this tectonic plate, is a barrier to its movement. But I can feel the vines withering, their complicity in the substrata’s effect on my psyche weakening.