Fall Waxing Harvest Moon

Let’s try darkness again. In Taoism the familiar Taiji makes my point about the essential and complementary nature of light and dark. Taoism gives equal weight to the yin and yang* represented in the taiji, the small circle of yin within the yang and of yang within the yin, emphasizing the Taoist belief that all things contain their opposite to some degree. So, one part of my argument simply notes that light and dark are both necessary, necessary to each other, nothing apart from each other. In the Taoist taiji they represent the dynamic movement of heaven to which all things must conform.

In our Western cultural tradition, though, light has taken precedence over darkness, both in a physical and in an ethical sense. Jesus is the light of the world. Persephone goes into Hades and the earth mourns her absence until her return when it blossoms into spring. Eurydice dies and Orpheus goes to the underworld to retrieve her. Dante’s Divine Comedy finds Dante wandering, lost in the dark wood of error, before he begins his descent, guided by Virgil, into the multiple layers of hell. The traditional three-story universe also reinforces these ideas: Heaven above, earth, and the infernal regions below. Milton’s Paradise Lost follows the rebellion in heaven and the casting out of Lucifer, the Morning Star, into hell where he builds his enormous palace, Pandemonium. Our common sense understanding of death involves hiding the body beneath the earth. Why?

Coming out of the spiritualist tradition represented by Camp Chesterfield (see below) death involves a transition into the light, the spirit world. Ghost Whisperer, a TV program, uses the trope from this tradition, as dead souls are led into the light. It is, perhaps, no wonder that darkness, night and the soil come off badly in our folk metaphysic: up and light is good; down and dark is bad.

I wish to speak a word for the yin, symbolized by the moon, the female, the cold, the receiving, the dark. The moon illustrates the taiji perfectly. In the dark of night, the moon, yin, reflects the sun’s light, yang, and offers a lambent light, neither yin nor yang, but the dynamic interplay between the two. So we could look for art that features the moon as one route into the positive power of darkness.

Also, any seasonal display in a work of art, whether of spring, summer, fall or winter can open the question of each season’s value, its role in the dynamic of growth and decay, emergence and return. This can lead to a discussion of the importance of the fallow season, the season of rest, the earth’s analog to sleep. This can lead to a discussion of sleep and its restorative powers.

Art work of mother and child, or especially, mother and infant, can stimulate a discussion, in this context, of the womb, of the fecund nature of the dark where fetuses and seeds develop before their emergence into the world of light.

Similarly, death focused works of art can open up a discussion of birth and death as dynamic moments of change, yin and yang of human (or animal) development. This could lead to conversation about the Mexica (Aztec) belief that life is the aberrant condition and that death is the vital, regenerative moment; we are here, goes one Mexica poem, between a sleep and a sleep.

Winterlight festivals represent a western imbalance focused on the light, the yang, and a tendency to cast the yin in a negative light, something to be avoided or eliminated or held in check. As I said previously, this is understandable given the pre-historical science which made the return of the sun doubtful and therefore terrifying. Many of these festivals are, too, our favorites: Christmas, Deepavali and for a different traditional reason, Hanukkah.

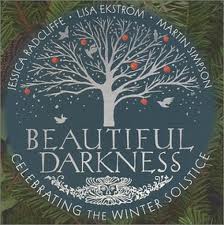

In my own faith tradition, roughly pagan, I look forward to the dying of the light and celebrate as my most meaningful holiday, the Winter Solstice. Of course, I also celebrate the return of the light that begins on that very day, but first I immerse myself in the long night, the many hours of darkness. This affords me an opportunity to acknowledge the dark, to express gratitude for its manifold gifts. In this way my idiosyncratic faith has a ritual moment that honors the taiji, utilizing the cues given by the natural world.

To find art that emphasizes this aspect of darkness I plan to walk the museum from top to bottom, searching for images and objects that can help our visitors understand that when they celebrate the festivals of light that darkness is the reason for the season. I would appreciate any thoughts or ideas.

*In Chinese culture, Yin and Yang represent the two opposite principles in nature. Yin characterizes the feminine or negative nature of things and yang stands for the masculine or positive side. Yin and yang are in pairs, such as the moon and the sun, female and male, dark and bright, cold and hot, passive and active, etc. But yin and yang are not static or just two separated things. The nature of yinyang lies in interchange and interplay of the two components. The alternation of day and night is such an example.

share a darkness dispelling theme with the others.

share a darkness dispelling theme with the others.