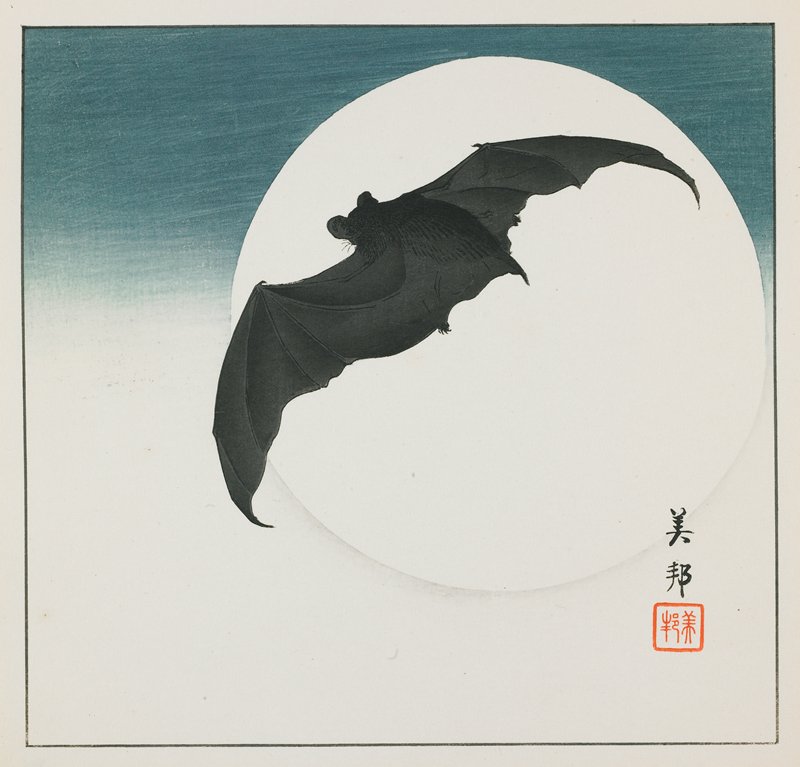

Spring Recovery Moon

First, it’s not about gypsies. Roma is a neighborhood in Mexico City.

Second, it’s not a thriller, or a mystery, or a comedy (except perhaps of manners), or a drama. It’s not fantasy, anime, or horror. I would call it cinema verité, a slice of life, in this case a short period in the life of Cleo, an indigenous woman who serves as a maid to the deteriorating family of a physician. She and Adela, another maid, wake up the children, kiss them and love them, make meals, clean the house, and work from morning until night.

Cleo is affectionate, a para-mother, to the four children, three boys and a girl. They love her back and the relationship among them is strong enough that, despite not knowing how to swim, she wades into the Bay of Campeche to save Sofi from drowning as threatening waves break all around them.

The film is told with Cleo and her life as its center, and a good part of it covers the evolution of her pregnancy, the result of one afternoon with Fermín. Fermín’s full frontal nudity, while brandishing a staff in martial arts fashion, serves to highlight what I perceived as the strongly feminist theme. His is the only nudity in the film.

Cleo’s pregnancy ends in the birth of a dead girl. The physician moves away from his home, leaving his wife, her mother, the four kids, Cleo and Adela in the family house. After a drunken drive into the garage with the oversized, masculine body of a Ford Galaxy, the wife says to Cleo, “We’re all alone Cleo. We women are always alone.” Her mother is there, alone. Cleo and Adela are there alone.

Cleo tells Fermín that she’s late while they are at a movie. He says, “That’s good, yeah?” She looks a little bewildered, but nods. “I’m going to the bathroom.” He disappears. When she finds him much later, he’s moved back to a village and trains there. She asks him if he has a minute. He shouts at her, brandishes his staff, “It’s not mine. If you come back, I’ll beat your face in.”

Though the film consistently portrays the physician’s family, including his wife, as caring for Cleo, “We love you, Cleo, very much.” there is always the underlying dynamic of employer/employee. “Will you fire me?” Cleo asks when informing the wife of her pregnancy. “Of course not.” The story from Cleo’s point of view suggests several different times that her position could be precarious, even if the family does love her.

We don’t see films focused on servants. Especially not films that take a more or less neutral attitude toward servitude like Roma. Yes, we see the threat to Cleo, but we also see the families genuine affection for her, the children’s, too. She displays no anger at her life, nor does Adela. Her most negative emotions come after the birth of her dead girl. She sits and stares.

The black and white film, the setting in the early 1970’s, and the depiction of an infamous police riot against protesting college students give Roma the patina of a story from long ago, as if the participants were sitting around a campfire somewhere recounting that year that Cleo got pregnant. In that sense, and in its third person style, gives the viewer a distance from the events in the movie, like watching a newsreel.

This is a powerful, well-observed film. It drew me in to Cleo’s world, made me ache with her, want more for her, appreciate her love for the children, which, of course, drew a double line of irony under her unsuccessful pregnancy.

Picked up sister-in-law BJ at DIA yesterday. She’s an experienced traveler with a single roll-on bag and bright blue, hard-shelled case which carries her violin. It goes everywhere with her, including in to Sushi Win for lunch. “Cold is not good for it. Changes in humidity.” She’s the concert master for the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, so the blue, hard-shelled case carries her means of earning a living.

Picked up sister-in-law BJ at DIA yesterday. She’s an experienced traveler with a single roll-on bag and bright blue, hard-shelled case which carries her violin. It goes everywhere with her, including in to Sushi Win for lunch. “Cold is not good for it. Changes in humidity.” She’s the concert master for the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, so the blue, hard-shelled case carries her means of earning a living. Shecky and a pianist with whom he often works, Hiroko Sasaki, have a performance scheduled at the

Shecky and a pianist with whom he often works, Hiroko Sasaki, have a performance scheduled at the  All three dogs love the snow. Rigel and Gertie both go into the drifts nose first, come up shaking their heads, then do it again. Rigel hunts the rabbits that live under the deck and the shed, but she’s never caught one here, as far as I know. Back in Andover, every once in a while. Kep likes to wander in the snow, his black and white body moving in and out of the drifts as he investigates. He’s usually the last one back inside. His genes, after all, hail from the Akita prefecture in Japan, famous for its mountains and snow.

All three dogs love the snow. Rigel and Gertie both go into the drifts nose first, come up shaking their heads, then do it again. Rigel hunts the rabbits that live under the deck and the shed, but she’s never caught one here, as far as I know. Back in Andover, every once in a while. Kep likes to wander in the snow, his black and white body moving in and out of the drifts as he investigates. He’s usually the last one back inside. His genes, after all, hail from the Akita prefecture in Japan, famous for its mountains and snow.

When you read the literature, it’s clear that exercise is not only beneficial, but necessary for good health, especially as we age. I didn’t start until my late 30’s and it took me a while to get regular at it. Now it feels weird to me if I don’t get in my workouts on a regular basis. The last two months were an anomaly and one I didn’t like.

When you read the literature, it’s clear that exercise is not only beneficial, but necessary for good health, especially as we age. I didn’t start until my late 30’s and it took me a while to get regular at it. Now it feels weird to me if I don’t get in my workouts on a regular basis. The last two months were an anomaly and one I didn’t like.

Go now, the illness has ended. Feeling 95%. Still something in my lungs, not much. So seven weeks after the molasses filled drive back from Denver, I feel able. Still got workouts and stamina to increase, but I enjoy that. Imagine me doing a little dance on the balcony of the loft, a dance of thanksgiving for a strong constitution and a return to the unremarkable state of health.

Go now, the illness has ended. Feeling 95%. Still something in my lungs, not much. So seven weeks after the molasses filled drive back from Denver, I feel able. Still got workouts and stamina to increase, but I enjoy that. Imagine me doing a little dance on the balcony of the loft, a dance of thanksgiving for a strong constitution and a return to the unremarkable state of health. Remember the Producers? Zero Mostel? In it was the classic hit, “It’s Springtime for Hitler”. Well, it’s springtime in the Rockies and all of Colorado. Here’s another pirouette for great comedies and a plié with arm extended for the beauty of Black Mountain.

Remember the Producers? Zero Mostel? In it was the classic hit, “It’s Springtime for Hitler”. Well, it’s springtime in the Rockies and all of Colorado. Here’s another pirouette for great comedies and a plié with arm extended for the beauty of Black Mountain. And, yes, in that state now, I feel resurrected, reborn, renewed. A little shaky perhaps but that fits such a state doesn’t it? What’s next? Not in the quotidian sense I mentioned above, but what’s next in the sense of “

And, yes, in that state now, I feel resurrected, reborn, renewed. A little shaky perhaps but that fits such a state doesn’t it? What’s next? Not in the quotidian sense I mentioned above, but what’s next in the sense of “ Head. Mostly clear. Lungs. Mostly clear. I’m beginning to feel the illness bidding me goodbye. So long, it was good to know ya. Nah, it wasn’t. And don’t come back, please.

Head. Mostly clear. Lungs. Mostly clear. I’m beginning to feel the illness bidding me goodbye. So long, it was good to know ya. Nah, it wasn’t. And don’t come back, please. I really don’t want to confuse Kate’s journey right now, especially since we see the same doc, so I may wait a bit, be sure the flight of respiratory illness I sampled over the last two months has actually ended. In time I would like to know if anything in my lungs compromises my breathing. It’s certainly possible. I smoked for 13 years. Not proud of it, but I did. I also worked in a couple of high particulate matter jobs in my younger days, cutting rags at a paper mill and moving completed asbestos ceiling tiles to pallets. And, Dad had severe asthma, using an inhaler virtually his whole life.

I really don’t want to confuse Kate’s journey right now, especially since we see the same doc, so I may wait a bit, be sure the flight of respiratory illness I sampled over the last two months has actually ended. In time I would like to know if anything in my lungs compromises my breathing. It’s certainly possible. I smoked for 13 years. Not proud of it, but I did. I also worked in a couple of high particulate matter jobs in my younger days, cutting rags at a paper mill and moving completed asbestos ceiling tiles to pallets. And, Dad had severe asthma, using an inhaler virtually his whole life. What impedes breathing, impedes life itself. Impedes the spirit of all life that dwells within us. Like health breathing is unremarkable to most of us until its ease experiences an interruption. Water boarding, or extreme interrogation (not torture as our CIA likes to say), is horrific because it emulates drowning. Our body has reflexes built in, the diving reflex, for example, that protect us in the case of sudden immersion in water. This means that our DNA carries a history of dangers to our breathing.

What impedes breathing, impedes life itself. Impedes the spirit of all life that dwells within us. Like health breathing is unremarkable to most of us until its ease experiences an interruption. Water boarding, or extreme interrogation (not torture as our CIA likes to say), is horrific because it emulates drowning. Our body has reflexes built in, the diving reflex, for example, that protect us in the case of sudden immersion in water. This means that our DNA carries a history of dangers to our breathing. A breathing issue is not, then, solely the province of pulmonology. It is also the province of theology broadly understood. Theology, for me, is the way you identify, organize, and deal with matters of ultimate importance. Life itself is, of course, a matter of ultimate importance to an individual; therefore, life and how it is for us at any particular point is a directly theological matter. Breath, the spirit of life that fills our lungs, provides our cells with oxygen so that they can carry out the physiological functions that are life in the body, is also of ultimate importance.

A breathing issue is not, then, solely the province of pulmonology. It is also the province of theology broadly understood. Theology, for me, is the way you identify, organize, and deal with matters of ultimate importance. Life itself is, of course, a matter of ultimate importance to an individual; therefore, life and how it is for us at any particular point is a directly theological matter. Breath, the spirit of life that fills our lungs, provides our cells with oxygen so that they can carry out the physiological functions that are life in the body, is also of ultimate importance.