Midsommar Most Heat Moon

Next week we all give 5-8 minute presentations in our kabbalah class. The ostensible purpose is for us to have the chance to “learn as teachers.” It will be more than that for me. At first I thought I would work up something about tikkun olam, repairing the world, or, as the early kabbalists preferred, repairing God. The notion fits nicely within my political activism (now shelved)/reimagining faith work. But that would have been the more traditional student as presenter, a small talk focused on the content of what I’ve begun to learn.

Next week we all give 5-8 minute presentations in our kabbalah class. The ostensible purpose is for us to have the chance to “learn as teachers.” It will be more than that for me. At first I thought I would work up something about tikkun olam, repairing the world, or, as the early kabbalists preferred, repairing God. The notion fits nicely within my political activism (now shelved)/reimagining faith work. But that would have been the more traditional student as presenter, a small talk focused on the content of what I’ve begun to learn.

Instead I’ve decided to go for it, to use the post below, Earthquake, as a starting point. I want to discuss my changing inner world, the push kabbalah has given me, adding its long standing contrarian position to my own.

Here’s how I imagine it might go right now.

Religion itself and sacred texts in particular as metaphors.

Kabbalah has reinforced and challenged a move I made many years ago away from the metaphysics of the Judaeo-Christian tradition as I understood it. I can summarize that move as a reaction against transcendence and its role in buttressing patriarchy. Transcendence moved me up and out of my body, up and out of my Self into a different a place, a place other than where I was, a better place, a place dominated by God. It didn’t really matter what image of God, what understanding of God you put in that sentence because it was the denial of the here and now, the embodiedness of us, that bothered me. The notion that transcendence puts us in a better place, a place only accessible outside of our bodies made us lesser creatures, doomed to spend most of our time in a less spiritual state. In the long tradition of a male imaged God it made that gender dominate because it was God that occupied the better place, the more spiritual place, the place, if we were lucky or faithful enough, that we might achieve permanently after death.

Kabbalah has reinforced and challenged a move I made many years ago away from the metaphysics of the Judaeo-Christian tradition as I understood it. I can summarize that move as a reaction against transcendence and its role in buttressing patriarchy. Transcendence moved me up and out of my body, up and out of my Self into a different a place, a place other than where I was, a better place, a place dominated by God. It didn’t really matter what image of God, what understanding of God you put in that sentence because it was the denial of the here and now, the embodiedness of us, that bothered me. The notion that transcendence puts us in a better place, a place only accessible outside of our bodies made us lesser creatures, doomed to spend most of our time in a less spiritual state. In the long tradition of a male imaged God it made that gender dominate because it was God that occupied the better place, the more spiritual place, the place, if we were lucky or faithful enough, that we might achieve permanently after death.

Going in and down became my primary metaphor for the spiritual life; spirituality became an inner journey, not a transcendent one. The body was not like a temple; it was a quite literal temple, a place, the place, where a journey toward understanding and meaning found its locus. It was natural, therefore, to leave Christianity and especially the Christian ministry, as this focus took hold of my pilgrimage.

This inner turn is what pagan means for me. It put spirituality more in the mode the Judaeo-Christian tradition terms incarnation, put a thumb on the scale for the notion of imago dei, rather than the three-story universe. Gardening and bee-keeping became ultimate spiritual practices. They made real, as real as can be, the whole immersion of this body in the web of life. Tomatoes, beets, leeks, garlic, raspberries, plums, apples, currants, beans, comb honey and liquid honey grew on our land, nurtured by our hands, then entered our bodies to actually, really become us. The true transubstantiation.

This inner turn is what pagan means for me. It put spirituality more in the mode the Judaeo-Christian tradition terms incarnation, put a thumb on the scale for the notion of imago dei, rather than the three-story universe. Gardening and bee-keeping became ultimate spiritual practices. They made real, as real as can be, the whole immersion of this body in the web of life. Tomatoes, beets, leeks, garlic, raspberries, plums, apples, currants, beans, comb honey and liquid honey grew on our land, nurtured by our hands, then entered our bodies to actually, really become us. The true transubstantiation.

The Great Wheel, the Celtic sacred calendar that follows the web of life as earth’s orbit changes our seasons, became my liturgical calendar. Observing the wheeling of the stars above our turning earth was the closest I got to transcendence.

Kabbalah has reinforced this move. By suggesting the radical, very radical, notion that even such sacred texts as the Torah are metaphorical, a garment for the soul of souls, for example, it makes each metaphor used more important. The metaphysical becomes metaphorical. Or, perhaps it always was. So, metaphors matter.

Kabbalah challenges this move. By acknowledging transcendence as a metaphor, it allows us to soften its patriarchal implications, to seek, if you will allow this phrase, a deeper meaning. I can imagine an understanding of transcendence that poses a horizontal rather than a vertical metaphor. Transcendence, understood this way, could embed us in community, place us in the web of life. A hug could become a transcendent moment, the touching of another, one outside our inner world. So could this class be a time when our inner worlds intersect, when our body language and our spoken language give us brief entre to the world of another. Even the example I used of the garden and bee-keeping can also be seen as transcendent, a way the outer becomes inner.

Transcendence was not the only theological problem I had with the Judaeo-Christian tradition, I’m using it here as an example, a key example, but only that. I won’t go further into those today with one exception.

When I moved away from transcendence, I moved toward this world. This world of sensation and my inner world became the whole, I sheared off the metaphysical almost as cleanly as my logical positivist philosophy had done, though for quite different reasons. No metaphysics, no God. No metaphysics, no transcendence. I switched to an ontology informed only by my senses or by the extended reach of our limited human senses occasioned by science. That meant this world, at both the micro and macro levels was the only world.

When I moved away from transcendence, I moved toward this world. This world of sensation and my inner world became the whole, I sheared off the metaphysical almost as cleanly as my logical positivist philosophy had done, though for quite different reasons. No metaphysics, no God. No metaphysics, no transcendence. I switched to an ontology informed only by my senses or by the extended reach of our limited human senses occasioned by science. That meant this world, at both the micro and macro levels was the only world.

Kabbalah has forced me to reconsider this drastic pulling back. It suggests a link between the hidden codes revealed by science and mathematics and the metaphorical nature of language. What language reveals, it also hides. The language of the Torah unveils; but, it also conceals. Not done with this, not even by a long shot of Zeno’s arrow.

Kabbalah. It’s trying to pry off the empiricist covering I’ve put on my world. I say trying because I’m a skeptic at heart, a doubter, a critic, an analyst yet also, and just as deeply, a poet, a lover of myth and fantasy, a dreamer.

Kabbalah. It’s trying to pry off the empiricist covering I’ve put on my world. I say trying because I’m a skeptic at heart, a doubter, a critic, an analyst yet also, and just as deeply, a poet, a lover of myth and fantasy, a dreamer. Rabbi Akiva says that nothing in nature is less miraculous than the rarest exception. This means, for example, that the water in the Red Sea (or, Reed Sea) is as miraculous as its parting. Or, for that matter, the Hebrew slaves pouring across it are, too.

Rabbi Akiva says that nothing in nature is less miraculous than the rarest exception. This means, for example, that the water in the Red Sea (or, Reed Sea) is as miraculous as its parting. Or, for that matter, the Hebrew slaves pouring across it are, too. It is anxiety. I believe it infested my life in two early stages. The first was polio, a young boy’s physical experience of our human finitude. It happened once; it could happen again. The second was the death of my mother when I was 17. It happened once, to Mom. It will happen to me and could happen quickly.

It is anxiety. I believe it infested my life in two early stages. The first was polio, a young boy’s physical experience of our human finitude. It happened once; it could happen again. The second was the death of my mother when I was 17. It happened once, to Mom. It will happen to me and could happen quickly. The wrong part is that it doesn’t matter. I don’t have to worry about it, fear it, be anxious about it. It is. Or, rather, will be. Maybe in the next ten minutes, maybe in the next ten years, maybe longer. I know this by reason, have known it for a long, long time, but I have not been able to displace the irrational fear in spite of that knowledge. That’s why I say reason can take me up to the wall, but not past it.

The wrong part is that it doesn’t matter. I don’t have to worry about it, fear it, be anxious about it. It is. Or, rather, will be. Maybe in the next ten minutes, maybe in the next ten years, maybe longer. I know this by reason, have known it for a long, long time, but I have not been able to displace the irrational fear in spite of that knowledge. That’s why I say reason can take me up to the wall, but not past it. Yet, increasingly I find myself wanting a way through this. I can sense, and here kabbalah is playing a critical alchemical role, a different world, a better world now hidden from me. I can peek through the vines at times, can see the secret garden beyond. It’s this wall that holds up the substrata, keeps it from being ground other parts of my Self. This wall has its roots sunk deep into this tectonic plate, is a barrier to its movement. But I can feel the vines withering, their complicity in the substrata’s effect on my psyche weakening.

Yet, increasingly I find myself wanting a way through this. I can sense, and here kabbalah is playing a critical alchemical role, a different world, a better world now hidden from me. I can peek through the vines at times, can see the secret garden beyond. It’s this wall that holds up the substrata, keeps it from being ground other parts of my Self. This wall has its roots sunk deep into this tectonic plate, is a barrier to its movement. But I can feel the vines withering, their complicity in the substrata’s effect on my psyche weakening. After leaving the ministry, a gradual process of demythologization and disenchantment took over. In retrospect it’s not hard to see why. A primary motivator of the shift away from Christianity and toward a more pagan worldview came because transcendence bothered me. Transcendence takes us up and out of our bodies, or least out and away from our bodies.

After leaving the ministry, a gradual process of demythologization and disenchantment took over. In retrospect it’s not hard to see why. A primary motivator of the shift away from Christianity and toward a more pagan worldview came because transcendence bothered me. Transcendence takes us up and out of our bodies, or least out and away from our bodies. Then, at some point-the reimagining faith project signals that point-the flat-earth humanism of this pagan orientation no longer felt like enough. Could the warmth and the depth available to those in the ancient religious traditions somehow be suffused into this empiricist, anti-metaphysical worldview? Could, in other words, a feeling of religious awe and wonder emerge out of our relationship with the web of life and the cosmic experiment we know as the universe?

Then, at some point-the reimagining faith project signals that point-the flat-earth humanism of this pagan orientation no longer felt like enough. Could the warmth and the depth available to those in the ancient religious traditions somehow be suffused into this empiricist, anti-metaphysical worldview? Could, in other words, a feeling of religious awe and wonder emerge out of our relationship with the web of life and the cosmic experiment we know as the universe? Transcendence still seems suspect. Reimagining though has to take account of it in some way. Here’s one idea. The mystical experience, a well documented and not at all rare phenomenon, often carries the descriptor transcendent. I had one and I want to challenge that idea. In mine, which occurred in 1967 on the quad at Ball State University, I did feel a sudden and inexplicable connection to the universe, all of it. Threads of light and power emanated in a pulsing glory carrying with them a physical sensation of oneness.

Transcendence still seems suspect. Reimagining though has to take account of it in some way. Here’s one idea. The mystical experience, a well documented and not at all rare phenomenon, often carries the descriptor transcendent. I had one and I want to challenge that idea. In mine, which occurred in 1967 on the quad at Ball State University, I did feel a sudden and inexplicable connection to the universe, all of it. Threads of light and power emanated in a pulsing glory carrying with them a physical sensation of oneness. Danced the hora last night, mixing up my feet as I normally do while dancing, but enjoying myself anyway. Joy, it turns out, is a character trait in mussar. “It’s a mitzvah to be happy.” Rabbi Nachman. Judaism constantly challenges my Midwestern protestant ethos, not primarily intellectually, but emotionally. Last night was a good example.

Danced the hora last night, mixing up my feet as I normally do while dancing, but enjoying myself anyway. Joy, it turns out, is a character trait in mussar. “It’s a mitzvah to be happy.” Rabbi Nachman. Judaism constantly challenges my Midwestern protestant ethos, not primarily intellectually, but emotionally. Last night was a good example. We ate our meal together outside, all at one picnic table. Tara’s Hebrew school students had decorated it and it was colorful underneath our paper plates and plastic bowls. The evening was a perfect combination of cool warmth and low humidity. The grandmother ponderosa stood tall, lightning scarred against the blue black sky. Bergen mountain had already obscured the sun which still lit up the clouds from its hiding place.

We ate our meal together outside, all at one picnic table. Tara’s Hebrew school students had decorated it and it was colorful underneath our paper plates and plastic bowls. The evening was a perfect combination of cool warmth and low humidity. The grandmother ponderosa stood tall, lightning scarred against the blue black sky. Bergen mountain had already obscured the sun which still lit up the clouds from its hiding place. We all laughed when Rabbi Jamie asked if I hoped (another middot, character trait, clustered with joy) to be able to greet strangers the same way. “Well, not by kissing them on the lips or licking them.” I was thinking, but yes, I hope I can add that level of uncalculated joy to my meetings with others.

We all laughed when Rabbi Jamie asked if I hoped (another middot, character trait, clustered with joy) to be able to greet strangers the same way. “Well, not by kissing them on the lips or licking them.” I was thinking, but yes, I hope I can add that level of uncalculated joy to my meetings with others.

Yet again, I didn’t follow this one completely, but the Lurianic God is a God in exile, separated from the shards. So when the Jews go into exile, they do so as one with their estranged God. The purpose of the Jews is to remind humanity of this estrangement and that we all have a role to play in overcoming it.

Yet again, I didn’t follow this one completely, but the Lurianic God is a God in exile, separated from the shards. So when the Jews go into exile, they do so as one with their estranged God. The purpose of the Jews is to remind humanity of this estrangement and that we all have a role to play in overcoming it. Looking for light in prison. An assignment for the kabbalah class tonight. Rabbi Jamie suggested watching a movie like Hurricane, about Rubin Carter. I thought of MLK and Letters from the Birmingham Jail and Nelson Mandela, too. Then I remembered a portion of the

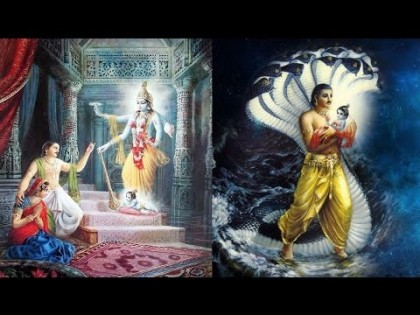

Looking for light in prison. An assignment for the kabbalah class tonight. Rabbi Jamie suggested watching a movie like Hurricane, about Rubin Carter. I thought of MLK and Letters from the Birmingham Jail and Nelson Mandela, too. Then I remembered a portion of the  Finally, nine years later, Devaki is pregnant again, this time with the eighth son Kansa dreaded. This son is Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu.

Finally, nine years later, Devaki is pregnant again, this time with the eighth son Kansa dreaded. This son is Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu.

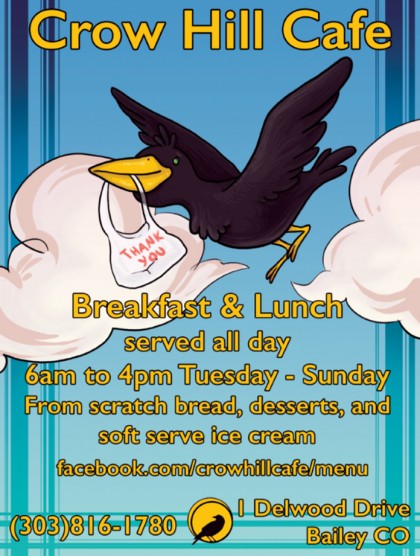

The go-go girls, Rigel and Gertie, joined me on a breakfast outing to Crow Hill Cafe. Crow Hill is the steep, 7% grade, that takes Hwy 285 down into Bailey. On the way there, from the western edge of Conifer, the continental divide defines the horizon, peaks until recently covered with snow. They allow us, who live in the mountains, to see the mountains in the same way folks in Denver can see the Front Range, as distant and majestic.

The go-go girls, Rigel and Gertie, joined me on a breakfast outing to Crow Hill Cafe. Crow Hill is the steep, 7% grade, that takes Hwy 285 down into Bailey. On the way there, from the western edge of Conifer, the continental divide defines the horizon, peaks until recently covered with snow. They allow us, who live in the mountains, to see the mountains in the same way folks in Denver can see the Front Range, as distant and majestic. Back to Conifer and the King Sooper. King Sooper is a Kroger chain upscale store, one listed as a potentially threatened species by newspaper articles about Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods. With the rapid concentration of certain retail activities we may need an endangered business protection act. King Sooper does deliver though we’ve not made use of that service. Those of us on Shadow Mountain don’t expect to see drones with celery and milk anytime soon.

Back to Conifer and the King Sooper. King Sooper is a Kroger chain upscale store, one listed as a potentially threatened species by newspaper articles about Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods. With the rapid concentration of certain retail activities we may need an endangered business protection act. King Sooper does deliver though we’ve not made use of that service. Those of us on Shadow Mountain don’t expect to see drones with celery and milk anytime soon. Neighbors and their dogs were on the sides of the road. Cell phones (pocket digital cameras) were out and aimed at the curve. The chop chop chop of helicopter rotors was evident, but the helicopter itself was not in sight. Then it was, slowly rising from the road, Flight for Life spelled out along the yellow stripe leading back to its stabilizers.

Neighbors and their dogs were on the sides of the road. Cell phones (pocket digital cameras) were out and aimed at the curve. The chop chop chop of helicopter rotors was evident, but the helicopter itself was not in sight. Then it was, slowly rising from the road, Flight for Life spelled out along the yellow stripe leading back to its stabilizers. It’s a very bright group around the table: a historian, a Berkeley trained lawyer, an organizational consultant, a Hebrew scholar, a rabbi in training, a second lawyer, a teenager with a good grasp of theoretical physics, two retired hospital administrators. This makes the conversation sparky, inspirational.

It’s a very bright group around the table: a historian, a Berkeley trained lawyer, an organizational consultant, a Hebrew scholar, a rabbi in training, a second lawyer, a teenager with a good grasp of theoretical physics, two retired hospital administrators. This makes the conversation sparky, inspirational. As our habitable space ship races along its track, its tilt gives us seasonal changes and four regular moments, two with roughly equal days and nights, the equinoxes, and two extremes: the solstices. The longest days of the year occur right now with the sun rising early and setting late ignoring Benjamin Franklin’s early to bed, early to rise. Six months from now, in the depths of midwinter, we will have the winter solstice where darkness prevails and long nights are the rule.

As our habitable space ship races along its track, its tilt gives us seasonal changes and four regular moments, two with roughly equal days and nights, the equinoxes, and two extremes: the solstices. The longest days of the year occur right now with the sun rising early and setting late ignoring Benjamin Franklin’s early to bed, early to rise. Six months from now, in the depths of midwinter, we will have the winter solstice where darkness prevails and long nights are the rule. At midsommar in the temperate latitudes where farms dominate the landscape, the growing season, which began roughly around Beltane, is now well underway. Wheat, corn, barley, soybeans, sorghum, sunflowers have risen from seed and fed by rain or irrigation make whole landscapes green with the intense colors of full growth. Midsommar mother earth once again works hard to feed her children.

At midsommar in the temperate latitudes where farms dominate the landscape, the growing season, which began roughly around Beltane, is now well underway. Wheat, corn, barley, soybeans, sorghum, sunflowers have risen from seed and fed by rain or irrigation make whole landscapes green with the intense colors of full growth. Midsommar mother earth once again works hard to feed her children. Our seasonal dance is not only, not even mostly, a metaphor, but is itself the rhythm of life. When its regularities falter, when either natural or artificial forces alter it, even a little, whole peoples, whole ecosystems experience stress, often death. We humans, as the Iroquois know, are ultimately fragile, our day to day lives dependent on the plant life and animal life around us. When they suffer, we begin to fail.

Our seasonal dance is not only, not even mostly, a metaphor, but is itself the rhythm of life. When its regularities falter, when either natural or artificial forces alter it, even a little, whole peoples, whole ecosystems experience stress, often death. We humans, as the Iroquois know, are ultimately fragile, our day to day lives dependent on the plant life and animal life around us. When they suffer, we begin to fail. The meaning of the Great Wheel, it’s rhythms, remains the same, a faithful cycling through earth’s changes as it plunges through dark space on its round. Their implications though, thanks to climate change, may shift, will shift in response to new temperature, moisture regimes. The summer solstice may be the moment each year when we begin, again, to realize the enormity of those shifts. It might be that the summer solstice will require new rituals, ones focused on gathering our power to both adapt to those shifts and alleviate the human actions ratcheting up the risks.

The meaning of the Great Wheel, it’s rhythms, remains the same, a faithful cycling through earth’s changes as it plunges through dark space on its round. Their implications though, thanks to climate change, may shift, will shift in response to new temperature, moisture regimes. The summer solstice may be the moment each year when we begin, again, to realize the enormity of those shifts. It might be that the summer solstice will require new rituals, ones focused on gathering our power to both adapt to those shifts and alleviate the human actions ratcheting up the risks.