Midsommar New (Kate’s) Moon

If you’re an alcoholic like I am, you learn early in treatment that the geographical escape won’t work. Wherever you go, there you are is the saying. It’s true that the addictive part of my personality follows me from place to place as well as through time. Even so, this move to Colorado has awakened me to an unexpected benefit of leaving a place, especially ones invested with a lot of meaning.

If you’re an alcoholic like I am, you learn early in treatment that the geographical escape won’t work. Wherever you go, there you are is the saying. It’s true that the addictive part of my personality follows me from place to place as well as through time. Even so, this move to Colorado has awakened me to an unexpected benefit of leaving a place, especially ones invested with a lot of meaning.

I lived in Minnesota over 40 years, moving to New Brighton in 1971 for seminary. I also lived in Alexandria, Indiana until I was 18, so two long stays in particular places. In the instance of Alexandria, I was there for all of my childhood. In Minnesota I became an adult, a husband and father, a minister and a writer.

Here’s the benefit. (which is also a source of grief) The reinforcements for memories and their feelings, the embeddedness of social roles sustained by seeing friends and family, even enemies, the sense of a self’s continuity that accrues in a place long inhabited, all these get adumbrated. There is no longer a drive near Sargent Avenue to go play sheepshead. Raeone and I moved to Sargent shortly before we got divorced. Neither docent friends nor the Woolly Mammoths show up on my calendar anymore with rare exceptions. No route takes me past the Hazelden outpatient treatment center that changed my life so dramatically.

While it’s true, in the wherever you go there you are sense, that these memories and social roles, the feeling of a continuous self that lived outside Nevis, in Irvine Park, worked at the God Box on Franklin Avenue remain, they are no longer a thick web in which I move and live and have my being, they no longer reinforce themselves on a daily, minute by minute basis. And so their impact fades.

While it’s true, in the wherever you go there you are sense, that these memories and social roles, the feeling of a continuous self that lived outside Nevis, in Irvine Park, worked at the God Box on Franklin Avenue remain, they are no longer a thick web in which I move and live and have my being, they no longer reinforce themselves on a daily, minute by minute basis. And so their impact fades.

On the other hand, in Colorado, there were many fewer memories and those almost all related to Jon, Jen and the grandkids. When we came here, we had never driven on Highway 285, never lived in the mountains, never attended a synagogue together. We hadn’t experienced altitude on a continuous basis, hadn’t seen the aspen go gold in the fall, had the solar snow shovel clear our driveway.

This is obvious, yes, but its effect is not. This unexperienced territory leaves open the possibility of new aspects of the self emerging triggered by new relationships, new roles, new physical anchors for memories. Evergreen, for example, now plays a central part in our weekly life. We go over there for Beth Evergreen. We go there to eat. Jon and the grandkids are going there to play in the lake this morning.

This is obvious, yes, but its effect is not. This unexperienced territory leaves open the possibility of new aspects of the self emerging triggered by new relationships, new roles, new physical anchors for memories. Evergreen, for example, now plays a central part in our weekly life. We go over there for Beth Evergreen. We go there to eat. Jon and the grandkids are going there to play in the lake this morning.

Deer Creek Canyon now has a deep association with mortality for me since it was the path I drove home after my prostate cancer diagnosis. Its rocky sides taught me that my illness was a miniscule part of a mountain’s lifetime and that comforted me.

This new place, this Colorado, is a third phase home. Like Alexandria for childhood and Minnesota for adulthood, Colorado will shape the last phase of life. Already it has offered an ancient faith tradition’s insights about that journey. Already it has offered a magnificent, a beautiful setting for our final years. Already it has placed us firmly in the life of Jon, Ruth and Gabe as we’ve helped them all navigate through the wilderness of loss. These are what get reinforced for us by the drives we take, the shopping we do, the medical care we receive, the places we eat family meals. And we’re changing, as people, as we experience all these things.

Well over fifty years ago Harrison Street in Alexandria ceased to be my main street. The Madison County fair was no longer an annual event. Mom was no longer alive. Of course, those years of paper routes, classrooms, playing in the streets have shaped who I am today, but I am no longer a child just as I am longer the adult focused on family and career that I was in Minnesota.

Wherever you go, there you change.

As our habitable space ship races along its track, its tilt gives us seasonal changes and four regular moments, two with roughly equal days and nights, the equinoxes, and two extremes: the solstices. The longest days of the year occur right now with the sun rising early and setting late ignoring Benjamin Franklin’s early to bed, early to rise. Six months from now, in the depths of midwinter, we will have the winter solstice where darkness prevails and long nights are the rule.

As our habitable space ship races along its track, its tilt gives us seasonal changes and four regular moments, two with roughly equal days and nights, the equinoxes, and two extremes: the solstices. The longest days of the year occur right now with the sun rising early and setting late ignoring Benjamin Franklin’s early to bed, early to rise. Six months from now, in the depths of midwinter, we will have the winter solstice where darkness prevails and long nights are the rule. At midsommar in the temperate latitudes where farms dominate the landscape, the growing season, which began roughly around Beltane, is now well underway. Wheat, corn, barley, soybeans, sorghum, sunflowers have risen from seed and fed by rain or irrigation make whole landscapes green with the intense colors of full growth. Midsommar mother earth once again works hard to feed her children.

At midsommar in the temperate latitudes where farms dominate the landscape, the growing season, which began roughly around Beltane, is now well underway. Wheat, corn, barley, soybeans, sorghum, sunflowers have risen from seed and fed by rain or irrigation make whole landscapes green with the intense colors of full growth. Midsommar mother earth once again works hard to feed her children. Our seasonal dance is not only, not even mostly, a metaphor, but is itself the rhythm of life. When its regularities falter, when either natural or artificial forces alter it, even a little, whole peoples, whole ecosystems experience stress, often death. We humans, as the Iroquois know, are ultimately fragile, our day to day lives dependent on the plant life and animal life around us. When they suffer, we begin to fail.

Our seasonal dance is not only, not even mostly, a metaphor, but is itself the rhythm of life. When its regularities falter, when either natural or artificial forces alter it, even a little, whole peoples, whole ecosystems experience stress, often death. We humans, as the Iroquois know, are ultimately fragile, our day to day lives dependent on the plant life and animal life around us. When they suffer, we begin to fail. The meaning of the Great Wheel, it’s rhythms, remains the same, a faithful cycling through earth’s changes as it plunges through dark space on its round. Their implications though, thanks to climate change, may shift, will shift in response to new temperature, moisture regimes. The summer solstice may be the moment each year when we begin, again, to realize the enormity of those shifts. It might be that the summer solstice will require new rituals, ones focused on gathering our power to both adapt to those shifts and alleviate the human actions ratcheting up the risks.

The meaning of the Great Wheel, it’s rhythms, remains the same, a faithful cycling through earth’s changes as it plunges through dark space on its round. Their implications though, thanks to climate change, may shift, will shift in response to new temperature, moisture regimes. The summer solstice may be the moment each year when we begin, again, to realize the enormity of those shifts. It might be that the summer solstice will require new rituals, ones focused on gathering our power to both adapt to those shifts and alleviate the human actions ratcheting up the risks. The shift to Reimagining has happened faster than I thought it would. My mind is like Kepler, our only dog who likes toys. He has a whole box of toys and he goes into it, noses around, finds the one he likes (why that one? no idea.), takes it out and carries it over to a place he’s decided is his toy stash area. I have several ideas that I’ve been playing with for years, e.g. becoming native to this place, emergence, tactile spirituality. In ways I don’t understand my mind goes over to the box of these ideas, hunts around, selects one and puts it front and center for maybe a second, maybe longer. Sometimes I pick up and play with one for awhile.

The shift to Reimagining has happened faster than I thought it would. My mind is like Kepler, our only dog who likes toys. He has a whole box of toys and he goes into it, noses around, finds the one he likes (why that one? no idea.), takes it out and carries it over to a place he’s decided is his toy stash area. I have several ideas that I’ve been playing with for years, e.g. becoming native to this place, emergence, tactile spirituality. In ways I don’t understand my mind goes over to the box of these ideas, hunts around, selects one and puts it front and center for maybe a second, maybe longer. Sometimes I pick up and play with one for awhile. In the shower one day I began to wonder where our water came from. At the time Kate and I lived on Edgcumbe Avenue in St. Paul so the question really was, where did St. Paul get its water? I had no idea. Turns out St. Paul public works pumps water out of the Mississippi and into a chain of lakes including Pleasant Lake and Sucker Lake just across the Anoka County border in Ramsey County north of St. Paul.

In the shower one day I began to wonder where our water came from. At the time Kate and I lived on Edgcumbe Avenue in St. Paul so the question really was, where did St. Paul get its water? I had no idea. Turns out St. Paul public works pumps water out of the Mississippi and into a chain of lakes including Pleasant Lake and Sucker Lake just across the Anoka County border in Ramsey County north of St. Paul. Though I haven’t done it, it would be possible to track back much further to the arrival of water on earth. This is a very interesting topic which I raise only to demonstrate the potential in this kind of thinking.

Though I haven’t done it, it would be possible to track back much further to the arrival of water on earth. This is a very interesting topic which I raise only to demonstrate the potential in this kind of thinking. Open the refrigerator. Where did the food come from? How about the carpet on your floor? The roofing material. Concrete. Paint. How about the car in your garage? Where was it built? What sort of materials go into making it? Where do they come from?

Open the refrigerator. Where did the food come from? How about the carpet on your floor? The roofing material. Concrete. Paint. How about the car in your garage? Where was it built? What sort of materials go into making it? Where do they come from? The incredible complexity of this web has put a thick wall between our daily lives and the earthiness of all that is around us. We start the car, shift into drive and head out to work or the store or on vacation dulled to the effort expended on the gasoline that fuels it, the rubber in the tires, the precious metals and the not-so precious metals in the body and frame and engine. I’m not talking right now about a car’s implication in climate change, or economic injustice, or urban planning. I’m focusing on getting to know how it came to be, what of our world made it possible.

The incredible complexity of this web has put a thick wall between our daily lives and the earthiness of all that is around us. We start the car, shift into drive and head out to work or the store or on vacation dulled to the effort expended on the gasoline that fuels it, the rubber in the tires, the precious metals and the not-so precious metals in the body and frame and engine. I’m not talking right now about a car’s implication in climate change, or economic injustice, or urban planning. I’m focusing on getting to know how it came to be, what of our world made it possible. Why? Because focusing on these things, deconstructing our things, begins to break the spell of modernism. Modernism offers us in the developed world a world prepackaged for our needs, organized so that we don’t have to till the field anymore, or hitch up the horse, or drop a bucket down a well. In so doing it waves the wand of mystification over our senses, blinding us to the mines, the aquifers, the oil fields, the vegetable fields, the landfills, the seeds and chemicals required to sustain us. This enchantment is the first barrier to a reimagined faith, to placing ourselves once again in the world.

Why? Because focusing on these things, deconstructing our things, begins to break the spell of modernism. Modernism offers us in the developed world a world prepackaged for our needs, organized so that we don’t have to till the field anymore, or hitch up the horse, or drop a bucket down a well. In so doing it waves the wand of mystification over our senses, blinding us to the mines, the aquifers, the oil fields, the vegetable fields, the landfills, the seeds and chemicals required to sustain us. This enchantment is the first barrier to a reimagined faith, to placing ourselves once again in the world. Reimagining Faith has been a project of mine since I slipped out of the Unitarian Universalist world leaving behind both Christianity and liberal religion, the first too narrow in its theology, the second too thin a broth. The stimulation for the project lay first in a decision I made to focus on my Celtic heritage for the writing I wanted to do. This commitment led me to the Great Wheel of the Year and its manifestation literally took root in the work Kate and I did at our Andover home.

Reimagining Faith has been a project of mine since I slipped out of the Unitarian Universalist world leaving behind both Christianity and liberal religion, the first too narrow in its theology, the second too thin a broth. The stimulation for the project lay first in a decision I made to focus on my Celtic heritage for the writing I wanted to do. This commitment led me to the Great Wheel of the Year and its manifestation literally took root in the work Kate and I did at our Andover home. In retrospect our request to him to make it all as low maintenance as possible seems laughable. He did as we wanted, putting in such sturdy plants as Stella D’oro, a species of daylily, shrubs, a bur oak and a Norwegian pine, some amur maples, a hardy brand of shrub rose, juniper, yew, a magnolia that Kate wanted, and a river birch. This work included an in-ground irrigation system and the very strange experience of having no lawn until one morning when the sod people came and rolled it out. Then we had a lawn that evening.

In retrospect our request to him to make it all as low maintenance as possible seems laughable. He did as we wanted, putting in such sturdy plants as Stella D’oro, a species of daylily, shrubs, a bur oak and a Norwegian pine, some amur maples, a hardy brand of shrub rose, juniper, yew, a magnolia that Kate wanted, and a river birch. This work included an in-ground irrigation system and the very strange experience of having no lawn until one morning when the sod people came and rolled it out. Then we had a lawn that evening. We looked at it, saw that it was good and thought we were done. Ha. It began with a desire for flowers. I wanted to have fresh flowers available throughout the growing season, so I studied perennials. At that time I thought I was still holding to the low maintenance idea. I would plant perennials that would bloom throughout the Minnesota growing season, roughly May 15 to September 15, go out occasionally and cut the blooms, put them in a vase, repeat until frost killed them all back. Then, the next year the perennials would return and the process would recur. Easy, right?

We looked at it, saw that it was good and thought we were done. Ha. It began with a desire for flowers. I wanted to have fresh flowers available throughout the growing season, so I studied perennials. At that time I thought I was still holding to the low maintenance idea. I would plant perennials that would bloom throughout the Minnesota growing season, roughly May 15 to September 15, go out occasionally and cut the blooms, put them in a vase, repeat until frost killed them all back. Then, the next year the perennials would return and the process would recur. Easy, right? Once this world opened up to us, we began to enjoy working with all these variables to create beauty around our home. Gardening for flowers, eh? Well, how about some vegetables. This led to a two-year project of cutting down thorny black locust, chipping the branches, then hiring a stump grinder. After this was done, Jon built us several raised beds. We filled them with good soil and compost. Tomatoes, potatoes, beans, garlic, leeks, onions, carrots, beets flourished. Vegetables, eh? Why not fruit and nuts?

Once this world opened up to us, we began to enjoy working with all these variables to create beauty around our home. Gardening for flowers, eh? Well, how about some vegetables. This led to a two-year project of cutting down thorny black locust, chipping the branches, then hiring a stump grinder. After this was done, Jon built us several raised beds. We filled them with good soil and compost. Tomatoes, potatoes, beans, garlic, leeks, onions, carrots, beets flourished. Vegetables, eh? Why not fruit and nuts? Ecological Gardens came in with permaculture principles and added apple trees, plums, cherry trees, pears, currants, gooseberry bushes, blueberry bushes and hawthorns. On the vegetable garden site they added raspberries, a sun trap for tomatoes, and an herb spiral. At that point then we were maintaining multiple perennial flower beds, several vegetable beds, fruit trees and the bees that I had started keeping.

Ecological Gardens came in with permaculture principles and added apple trees, plums, cherry trees, pears, currants, gooseberry bushes, blueberry bushes and hawthorns. On the vegetable garden site they added raspberries, a sun trap for tomatoes, and an herb spiral. At that point then we were maintaining multiple perennial flower beds, several vegetable beds, fruit trees and the bees that I had started keeping. When I stepped away from the Presbyterian ministry after marrying Kate, the Celtic pagan faith reflected in the Great Wheel began to inform my theological bent more and more. What was to come in the place of the Christian path? Perhaps it was a way of understanding our human journey, our pilgrimage as part of the planet on which we live rather than as separate from it or dominate over it.

When I stepped away from the Presbyterian ministry after marrying Kate, the Celtic pagan faith reflected in the Great Wheel began to inform my theological bent more and more. What was to come in the place of the Christian path? Perhaps it was a way of understanding our human journey, our pilgrimage as part of the planet on which we live rather than as separate from it or dominate over it. I have finished 7 novels and am nearing completion of an 8th. So I can work on a long term project and see it through to completion. I’ve also been part of creating several organizations still in existence in Minnesota, among them MICAH, Jobs Now, and The Minnesota Council of NonProfits (originally the Philanthropy Project). These, too, are long term efforts that I helped see to completion.

I have finished 7 novels and am nearing completion of an 8th. So I can work on a long term project and see it through to completion. I’ve also been part of creating several organizations still in existence in Minnesota, among them MICAH, Jobs Now, and The Minnesota Council of NonProfits (originally the Philanthropy Project). These, too, are long term efforts that I helped see to completion. I’ve had less persistence in my two non-fiction writing projects: an ecological history of Lake Superior and Reimagining Faith. Not sure why. Getting started on the research and idea end was not a problem, I have file folders, bookshelves, posts here on Ancientrails and various sketches for outlines. But I’ve never sustained the push to finish.

I’ve had less persistence in my two non-fiction writing projects: an ecological history of Lake Superior and Reimagining Faith. Not sure why. Getting started on the research and idea end was not a problem, I have file folders, bookshelves, posts here on Ancientrails and various sketches for outlines. But I’ve never sustained the push to finish. This morning I fed the dogs as I usually do, but I left them inside, no longer willing to risk a mountain lion attack. Mountain lions add frisson to life in the Front Range Rockies. It’s similar to driving in well below zero weather.

This morning I fed the dogs as I usually do, but I left them inside, no longer willing to risk a mountain lion attack. Mountain lions add frisson to life in the Front Range Rockies. It’s similar to driving in well below zero weather. Mountain lions and bears, oh my, are not the only fauna here that can hurt you. At lower elevations there are timber rattlers. There are also black widow and brown recluse spiders, all venomous enough to cause great harm. In these hills we find not the sound of music, but the shake of a snake’s tail. Julie Andrews might not skip so blithely here.

Mountain lions and bears, oh my, are not the only fauna here that can hurt you. At lower elevations there are timber rattlers. There are also black widow and brown recluse spiders, all venomous enough to cause great harm. In these hills we find not the sound of music, but the shake of a snake’s tail. Julie Andrews might not skip so blithely here.

These are only the most visible, too. There is Penumbra, of course, the Children’s Theater, the Northeast Art District, various jazz venues (Denver has excellent jazz.), Theater in the Round, the Cowles Center and many, many more.

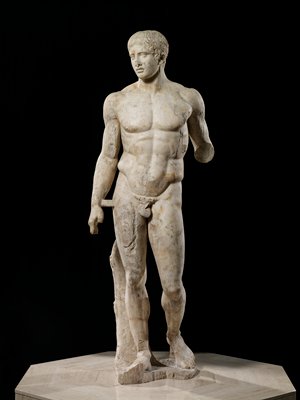

These are only the most visible, too. There is Penumbra, of course, the Children’s Theater, the Northeast Art District, various jazz venues (Denver has excellent jazz.), Theater in the Round, the Cowles Center and many, many more. Even with all these though I miss the relationship I had with Goya’s Dr. Arrieta, or the Bonnard, the Doryphoros, the Chinese and Japanese collections so important to my own aesthetic. Germanicus, Lucretia, the Rodin, Caillebotte, Beckman’s Blind Man’s Buff and the Kandinsky. I guess it’s the aesthetic equivalent of Toffler’s notion of high tech, high touch. That is, the more we use high technology, the more we need regular interaction with other people. I need regular interaction with actual works of art and they are simply not available here.

Even with all these though I miss the relationship I had with Goya’s Dr. Arrieta, or the Bonnard, the Doryphoros, the Chinese and Japanese collections so important to my own aesthetic. Germanicus, Lucretia, the Rodin, Caillebotte, Beckman’s Blind Man’s Buff and the Kandinsky. I guess it’s the aesthetic equivalent of Toffler’s notion of high tech, high touch. That is, the more we use high technology, the more we need regular interaction with other people. I need regular interaction with actual works of art and they are simply not available here.