Midsommar Most Heat Moon

Next week we all give 5-8 minute presentations in our kabbalah class. The ostensible purpose is for us to have the chance to “learn as teachers.” It will be more than that for me. At first I thought I would work up something about tikkun olam, repairing the world, or, as the early kabbalists preferred, repairing God. The notion fits nicely within my political activism (now shelved)/reimagining faith work. But that would have been the more traditional student as presenter, a small talk focused on the content of what I’ve begun to learn.

Next week we all give 5-8 minute presentations in our kabbalah class. The ostensible purpose is for us to have the chance to “learn as teachers.” It will be more than that for me. At first I thought I would work up something about tikkun olam, repairing the world, or, as the early kabbalists preferred, repairing God. The notion fits nicely within my political activism (now shelved)/reimagining faith work. But that would have been the more traditional student as presenter, a small talk focused on the content of what I’ve begun to learn.

Instead I’ve decided to go for it, to use the post below, Earthquake, as a starting point. I want to discuss my changing inner world, the push kabbalah has given me, adding its long standing contrarian position to my own.

Here’s how I imagine it might go right now.

Religion itself and sacred texts in particular as metaphors.

Kabbalah has reinforced and challenged a move I made many years ago away from the metaphysics of the Judaeo-Christian tradition as I understood it. I can summarize that move as a reaction against transcendence and its role in buttressing patriarchy. Transcendence moved me up and out of my body, up and out of my Self into a different a place, a place other than where I was, a better place, a place dominated by God. It didn’t really matter what image of God, what understanding of God you put in that sentence because it was the denial of the here and now, the embodiedness of us, that bothered me. The notion that transcendence puts us in a better place, a place only accessible outside of our bodies made us lesser creatures, doomed to spend most of our time in a less spiritual state. In the long tradition of a male imaged God it made that gender dominate because it was God that occupied the better place, the more spiritual place, the place, if we were lucky or faithful enough, that we might achieve permanently after death.

Kabbalah has reinforced and challenged a move I made many years ago away from the metaphysics of the Judaeo-Christian tradition as I understood it. I can summarize that move as a reaction against transcendence and its role in buttressing patriarchy. Transcendence moved me up and out of my body, up and out of my Self into a different a place, a place other than where I was, a better place, a place dominated by God. It didn’t really matter what image of God, what understanding of God you put in that sentence because it was the denial of the here and now, the embodiedness of us, that bothered me. The notion that transcendence puts us in a better place, a place only accessible outside of our bodies made us lesser creatures, doomed to spend most of our time in a less spiritual state. In the long tradition of a male imaged God it made that gender dominate because it was God that occupied the better place, the more spiritual place, the place, if we were lucky or faithful enough, that we might achieve permanently after death.

Going in and down became my primary metaphor for the spiritual life; spirituality became an inner journey, not a transcendent one. The body was not like a temple; it was a quite literal temple, a place, the place, where a journey toward understanding and meaning found its locus. It was natural, therefore, to leave Christianity and especially the Christian ministry, as this focus took hold of my pilgrimage.

This inner turn is what pagan means for me. It put spirituality more in the mode the Judaeo-Christian tradition terms incarnation, put a thumb on the scale for the notion of imago dei, rather than the three-story universe. Gardening and bee-keeping became ultimate spiritual practices. They made real, as real as can be, the whole immersion of this body in the web of life. Tomatoes, beets, leeks, garlic, raspberries, plums, apples, currants, beans, comb honey and liquid honey grew on our land, nurtured by our hands, then entered our bodies to actually, really become us. The true transubstantiation.

This inner turn is what pagan means for me. It put spirituality more in the mode the Judaeo-Christian tradition terms incarnation, put a thumb on the scale for the notion of imago dei, rather than the three-story universe. Gardening and bee-keeping became ultimate spiritual practices. They made real, as real as can be, the whole immersion of this body in the web of life. Tomatoes, beets, leeks, garlic, raspberries, plums, apples, currants, beans, comb honey and liquid honey grew on our land, nurtured by our hands, then entered our bodies to actually, really become us. The true transubstantiation.

The Great Wheel, the Celtic sacred calendar that follows the web of life as earth’s orbit changes our seasons, became my liturgical calendar. Observing the wheeling of the stars above our turning earth was the closest I got to transcendence.

Kabbalah has reinforced this move. By suggesting the radical, very radical, notion that even such sacred texts as the Torah are metaphorical, a garment for the soul of souls, for example, it makes each metaphor used more important. The metaphysical becomes metaphorical. Or, perhaps it always was. So, metaphors matter.

Kabbalah challenges this move. By acknowledging transcendence as a metaphor, it allows us to soften its patriarchal implications, to seek, if you will allow this phrase, a deeper meaning. I can imagine an understanding of transcendence that poses a horizontal rather than a vertical metaphor. Transcendence, understood this way, could embed us in community, place us in the web of life. A hug could become a transcendent moment, the touching of another, one outside our inner world. So could this class be a time when our inner worlds intersect, when our body language and our spoken language give us brief entre to the world of another. Even the example I used of the garden and bee-keeping can also be seen as transcendent, a way the outer becomes inner.

Transcendence was not the only theological problem I had with the Judaeo-Christian tradition, I’m using it here as an example, a key example, but only that. I won’t go further into those today with one exception.

When I moved away from transcendence, I moved toward this world. This world of sensation and my inner world became the whole, I sheared off the metaphysical almost as cleanly as my logical positivist philosophy had done, though for quite different reasons. No metaphysics, no God. No metaphysics, no transcendence. I switched to an ontology informed only by my senses or by the extended reach of our limited human senses occasioned by science. That meant this world, at both the micro and macro levels was the only world.

When I moved away from transcendence, I moved toward this world. This world of sensation and my inner world became the whole, I sheared off the metaphysical almost as cleanly as my logical positivist philosophy had done, though for quite different reasons. No metaphysics, no God. No metaphysics, no transcendence. I switched to an ontology informed only by my senses or by the extended reach of our limited human senses occasioned by science. That meant this world, at both the micro and macro levels was the only world.

Kabbalah has forced me to reconsider this drastic pulling back. It suggests a link between the hidden codes revealed by science and mathematics and the metaphorical nature of language. What language reveals, it also hides. The language of the Torah unveils; but, it also conceals. Not done with this, not even by a long shot of Zeno’s arrow.

Kabbalah. It’s trying to pry off the empiricist covering I’ve put on my world. I say trying because I’m a skeptic at heart, a doubter, a critic, an analyst yet also, and just as deeply, a poet, a lover of myth and fantasy, a dreamer.

Kabbalah. It’s trying to pry off the empiricist covering I’ve put on my world. I say trying because I’m a skeptic at heart, a doubter, a critic, an analyst yet also, and just as deeply, a poet, a lover of myth and fantasy, a dreamer. Rabbi Akiva says that nothing in nature is less miraculous than the rarest exception. This means, for example, that the water in the Red Sea (or, Reed Sea) is as miraculous as its parting. Or, for that matter, the Hebrew slaves pouring across it are, too.

Rabbi Akiva says that nothing in nature is less miraculous than the rarest exception. This means, for example, that the water in the Red Sea (or, Reed Sea) is as miraculous as its parting. Or, for that matter, the Hebrew slaves pouring across it are, too. It is anxiety. I believe it infested my life in two early stages. The first was polio, a young boy’s physical experience of our human finitude. It happened once; it could happen again. The second was the death of my mother when I was 17. It happened once, to Mom. It will happen to me and could happen quickly.

It is anxiety. I believe it infested my life in two early stages. The first was polio, a young boy’s physical experience of our human finitude. It happened once; it could happen again. The second was the death of my mother when I was 17. It happened once, to Mom. It will happen to me and could happen quickly. The wrong part is that it doesn’t matter. I don’t have to worry about it, fear it, be anxious about it. It is. Or, rather, will be. Maybe in the next ten minutes, maybe in the next ten years, maybe longer. I know this by reason, have known it for a long, long time, but I have not been able to displace the irrational fear in spite of that knowledge. That’s why I say reason can take me up to the wall, but not past it.

The wrong part is that it doesn’t matter. I don’t have to worry about it, fear it, be anxious about it. It is. Or, rather, will be. Maybe in the next ten minutes, maybe in the next ten years, maybe longer. I know this by reason, have known it for a long, long time, but I have not been able to displace the irrational fear in spite of that knowledge. That’s why I say reason can take me up to the wall, but not past it. Yet, increasingly I find myself wanting a way through this. I can sense, and here kabbalah is playing a critical alchemical role, a different world, a better world now hidden from me. I can peek through the vines at times, can see the secret garden beyond. It’s this wall that holds up the substrata, keeps it from being ground other parts of my Self. This wall has its roots sunk deep into this tectonic plate, is a barrier to its movement. But I can feel the vines withering, their complicity in the substrata’s effect on my psyche weakening.

Yet, increasingly I find myself wanting a way through this. I can sense, and here kabbalah is playing a critical alchemical role, a different world, a better world now hidden from me. I can peek through the vines at times, can see the secret garden beyond. It’s this wall that holds up the substrata, keeps it from being ground other parts of my Self. This wall has its roots sunk deep into this tectonic plate, is a barrier to its movement. But I can feel the vines withering, their complicity in the substrata’s effect on my psyche weakening. As our habitable space ship races along its track, its tilt gives us seasonal changes and four regular moments, two with roughly equal days and nights, the equinoxes, and two extremes: the solstices. The longest days of the year occur right now with the sun rising early and setting late ignoring Benjamin Franklin’s early to bed, early to rise. Six months from now, in the depths of midwinter, we will have the winter solstice where darkness prevails and long nights are the rule.

As our habitable space ship races along its track, its tilt gives us seasonal changes and four regular moments, two with roughly equal days and nights, the equinoxes, and two extremes: the solstices. The longest days of the year occur right now with the sun rising early and setting late ignoring Benjamin Franklin’s early to bed, early to rise. Six months from now, in the depths of midwinter, we will have the winter solstice where darkness prevails and long nights are the rule. At midsommar in the temperate latitudes where farms dominate the landscape, the growing season, which began roughly around Beltane, is now well underway. Wheat, corn, barley, soybeans, sorghum, sunflowers have risen from seed and fed by rain or irrigation make whole landscapes green with the intense colors of full growth. Midsommar mother earth once again works hard to feed her children.

At midsommar in the temperate latitudes where farms dominate the landscape, the growing season, which began roughly around Beltane, is now well underway. Wheat, corn, barley, soybeans, sorghum, sunflowers have risen from seed and fed by rain or irrigation make whole landscapes green with the intense colors of full growth. Midsommar mother earth once again works hard to feed her children. Our seasonal dance is not only, not even mostly, a metaphor, but is itself the rhythm of life. When its regularities falter, when either natural or artificial forces alter it, even a little, whole peoples, whole ecosystems experience stress, often death. We humans, as the Iroquois know, are ultimately fragile, our day to day lives dependent on the plant life and animal life around us. When they suffer, we begin to fail.

Our seasonal dance is not only, not even mostly, a metaphor, but is itself the rhythm of life. When its regularities falter, when either natural or artificial forces alter it, even a little, whole peoples, whole ecosystems experience stress, often death. We humans, as the Iroquois know, are ultimately fragile, our day to day lives dependent on the plant life and animal life around us. When they suffer, we begin to fail. The meaning of the Great Wheel, it’s rhythms, remains the same, a faithful cycling through earth’s changes as it plunges through dark space on its round. Their implications though, thanks to climate change, may shift, will shift in response to new temperature, moisture regimes. The summer solstice may be the moment each year when we begin, again, to realize the enormity of those shifts. It might be that the summer solstice will require new rituals, ones focused on gathering our power to both adapt to those shifts and alleviate the human actions ratcheting up the risks.

The meaning of the Great Wheel, it’s rhythms, remains the same, a faithful cycling through earth’s changes as it plunges through dark space on its round. Their implications though, thanks to climate change, may shift, will shift in response to new temperature, moisture regimes. The summer solstice may be the moment each year when we begin, again, to realize the enormity of those shifts. It might be that the summer solstice will require new rituals, ones focused on gathering our power to both adapt to those shifts and alleviate the human actions ratcheting up the risks.

Reimagining Faith has been a project of mine since I slipped out of the Unitarian Universalist world leaving behind both Christianity and liberal religion, the first too narrow in its theology, the second too thin a broth. The stimulation for the project lay first in a decision I made to focus on my Celtic heritage for the writing I wanted to do. This commitment led me to the Great Wheel of the Year and its manifestation literally took root in the work Kate and I did at our Andover home.

Reimagining Faith has been a project of mine since I slipped out of the Unitarian Universalist world leaving behind both Christianity and liberal religion, the first too narrow in its theology, the second too thin a broth. The stimulation for the project lay first in a decision I made to focus on my Celtic heritage for the writing I wanted to do. This commitment led me to the Great Wheel of the Year and its manifestation literally took root in the work Kate and I did at our Andover home. In retrospect our request to him to make it all as low maintenance as possible seems laughable. He did as we wanted, putting in such sturdy plants as Stella D’oro, a species of daylily, shrubs, a bur oak and a Norwegian pine, some amur maples, a hardy brand of shrub rose, juniper, yew, a magnolia that Kate wanted, and a river birch. This work included an in-ground irrigation system and the very strange experience of having no lawn until one morning when the sod people came and rolled it out. Then we had a lawn that evening.

In retrospect our request to him to make it all as low maintenance as possible seems laughable. He did as we wanted, putting in such sturdy plants as Stella D’oro, a species of daylily, shrubs, a bur oak and a Norwegian pine, some amur maples, a hardy brand of shrub rose, juniper, yew, a magnolia that Kate wanted, and a river birch. This work included an in-ground irrigation system and the very strange experience of having no lawn until one morning when the sod people came and rolled it out. Then we had a lawn that evening. We looked at it, saw that it was good and thought we were done. Ha. It began with a desire for flowers. I wanted to have fresh flowers available throughout the growing season, so I studied perennials. At that time I thought I was still holding to the low maintenance idea. I would plant perennials that would bloom throughout the Minnesota growing season, roughly May 15 to September 15, go out occasionally and cut the blooms, put them in a vase, repeat until frost killed them all back. Then, the next year the perennials would return and the process would recur. Easy, right?

We looked at it, saw that it was good and thought we were done. Ha. It began with a desire for flowers. I wanted to have fresh flowers available throughout the growing season, so I studied perennials. At that time I thought I was still holding to the low maintenance idea. I would plant perennials that would bloom throughout the Minnesota growing season, roughly May 15 to September 15, go out occasionally and cut the blooms, put them in a vase, repeat until frost killed them all back. Then, the next year the perennials would return and the process would recur. Easy, right? Once this world opened up to us, we began to enjoy working with all these variables to create beauty around our home. Gardening for flowers, eh? Well, how about some vegetables. This led to a two-year project of cutting down thorny black locust, chipping the branches, then hiring a stump grinder. After this was done, Jon built us several raised beds. We filled them with good soil and compost. Tomatoes, potatoes, beans, garlic, leeks, onions, carrots, beets flourished. Vegetables, eh? Why not fruit and nuts?

Once this world opened up to us, we began to enjoy working with all these variables to create beauty around our home. Gardening for flowers, eh? Well, how about some vegetables. This led to a two-year project of cutting down thorny black locust, chipping the branches, then hiring a stump grinder. After this was done, Jon built us several raised beds. We filled them with good soil and compost. Tomatoes, potatoes, beans, garlic, leeks, onions, carrots, beets flourished. Vegetables, eh? Why not fruit and nuts? Ecological Gardens came in with permaculture principles and added apple trees, plums, cherry trees, pears, currants, gooseberry bushes, blueberry bushes and hawthorns. On the vegetable garden site they added raspberries, a sun trap for tomatoes, and an herb spiral. At that point then we were maintaining multiple perennial flower beds, several vegetable beds, fruit trees and the bees that I had started keeping.

Ecological Gardens came in with permaculture principles and added apple trees, plums, cherry trees, pears, currants, gooseberry bushes, blueberry bushes and hawthorns. On the vegetable garden site they added raspberries, a sun trap for tomatoes, and an herb spiral. At that point then we were maintaining multiple perennial flower beds, several vegetable beds, fruit trees and the bees that I had started keeping. When I stepped away from the Presbyterian ministry after marrying Kate, the Celtic pagan faith reflected in the Great Wheel began to inform my theological bent more and more. What was to come in the place of the Christian path? Perhaps it was a way of understanding our human journey, our pilgrimage as part of the planet on which we live rather than as separate from it or dominate over it.

When I stepped away from the Presbyterian ministry after marrying Kate, the Celtic pagan faith reflected in the Great Wheel began to inform my theological bent more and more. What was to come in the place of the Christian path? Perhaps it was a way of understanding our human journey, our pilgrimage as part of the planet on which we live rather than as separate from it or dominate over it. I have finished 7 novels and am nearing completion of an 8th. So I can work on a long term project and see it through to completion. I’ve also been part of creating several organizations still in existence in Minnesota, among them MICAH, Jobs Now, and The Minnesota Council of NonProfits (originally the Philanthropy Project). These, too, are long term efforts that I helped see to completion.

I have finished 7 novels and am nearing completion of an 8th. So I can work on a long term project and see it through to completion. I’ve also been part of creating several organizations still in existence in Minnesota, among them MICAH, Jobs Now, and The Minnesota Council of NonProfits (originally the Philanthropy Project). These, too, are long term efforts that I helped see to completion. I’ve had less persistence in my two non-fiction writing projects: an ecological history of Lake Superior and Reimagining Faith. Not sure why. Getting started on the research and idea end was not a problem, I have file folders, bookshelves, posts here on Ancientrails and various sketches for outlines. But I’ve never sustained the push to finish.

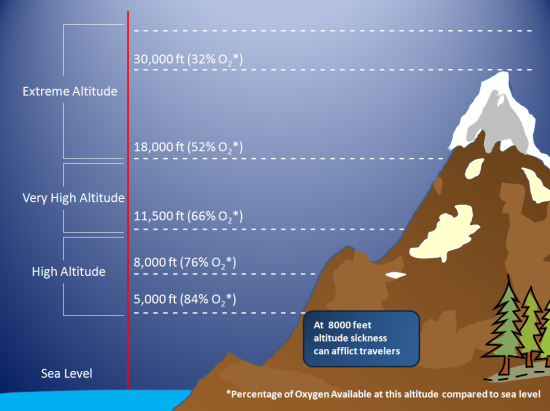

I’ve had less persistence in my two non-fiction writing projects: an ecological history of Lake Superior and Reimagining Faith. Not sure why. Getting started on the research and idea end was not a problem, I have file folders, bookshelves, posts here on Ancientrails and various sketches for outlines. But I’ve never sustained the push to finish. So. Because physics. No black tea up here, at least not at a proper temperature. Thanks Tom and Bill for your help. When you relieve the pressure, the water reverts to the pressure of the air and the temp goes down as it does. Sigh.

So. Because physics. No black tea up here, at least not at a proper temperature. Thanks Tom and Bill for your help. When you relieve the pressure, the water reverts to the pressure of the air and the temp goes down as it does. Sigh. Went into Kate’s hairstylist with her yesterday and got my ears waxed. Jackie put hot wax on my ears, then pulled it off, removing those hairs that seemed to follow receipt of my Medicare card. This is my second time. She says if we do this often enough, the follicles will not push up hair. I mean, hair on the ears is so last iteration of our species.

Went into Kate’s hairstylist with her yesterday and got my ears waxed. Jackie put hot wax on my ears, then pulled it off, removing those hairs that seemed to follow receipt of my Medicare card. This is my second time. She says if we do this often enough, the follicles will not push up hair. I mean, hair on the ears is so last iteration of our species. Planted a tomato plant yesterday in a five-gallon plastic bucket. When I opened the bag of garden soil (we don’t have anything a Midwesterner would recognize as soil), the smell of the earth almost made me cry. I miss working in soil, growing plants and my body told me so. A greenhouse went up higher on the priority list.

Planted a tomato plant yesterday in a five-gallon plastic bucket. When I opened the bag of garden soil (we don’t have anything a Midwesterner would recognize as soil), the smell of the earth almost made me cry. I miss working in soil, growing plants and my body told me so. A greenhouse went up higher on the priority list.

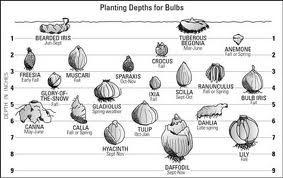

Yet it is not a true analog. Mother earth only seems to defy winter and the fallow time. It is not, in fact, death and resurrection, but a continuum of growth, slowed in the cold, yes, but not stopped forever, then magically restarted. Corms, bulbs, tubers and rhizomes all store energy from the previous growing season and wait only for the right temperature changes to release it. Seeds sown by wind and animal, by human hand are not dead either. They only await water and the right amount of light to send out roots and stalks.

Yet it is not a true analog. Mother earth only seems to defy winter and the fallow time. It is not, in fact, death and resurrection, but a continuum of growth, slowed in the cold, yes, but not stopped forever, then magically restarted. Corms, bulbs, tubers and rhizomes all store energy from the previous growing season and wait only for the right temperature changes to release it. Seeds sown by wind and animal, by human hand are not dead either. They only await water and the right amount of light to send out roots and stalks. I prefer the actual analog in which human and other animals’ bodies, plant parts and the detritus of other kingdoms, all life, return their borrowed materials to the inanimate cache, allowing them to be reincarnated in plant and animal alike, ad infinitum. Does this deny some metaphysical change, some butterfly-like imaginal cell possibility for the human soul? No. It claims what can be claimed, while reserving judgment on those things that cannot.

I prefer the actual analog in which human and other animals’ bodies, plant parts and the detritus of other kingdoms, all life, return their borrowed materials to the inanimate cache, allowing them to be reincarnated in plant and animal alike, ad infinitum. Does this deny some metaphysical change, some butterfly-like imaginal cell possibility for the human soul? No. It claims what can be claimed, while reserving judgment on those things that cannot. It is spring, I think, that gives us this hope, no matter how faint, that death might be only a phase change, a transition from this way of becoming to another. It’s possible.

It is spring, I think, that gives us this hope, no matter how faint, that death might be only a phase change, a transition from this way of becoming to another. It’s possible.