Lughnasa Waning Summer Moon

Alan came over for work on the religious school lesson plans. Kate made her oven pancakes (always delicious) and Alan told us stories about early Jewish Denver. West Colfax (think Lake Street) between Federal and Sheridan was an orthodox Jewish community when he grew up. He said on Friday afternoons with folks scurrying from the deli to the bakery to the kosher butcher it looked like, well I can’t recall exactly, but any typical European Jewish community.

His dad was going to be a University professor before the Holocaust. Instead he came here and ended up in the dry cleaning business. In those day Alan’s friends and neighbors were either children of Holocaust survivors or survivors themselves. That old neighborhood, like north Minneapolis, has completely changed. The first synagogue in Denver is now an art museum on the Auraria campus of the University of Colorado. The Jewish community concentrated itself in south Denver, more to the east.

We worked for a couple of hours, putting specific lesson plans on the calendar, deciding which days to do the Moving Traditions curriculum, which days for middah, which days for Jewish holidays, which days for our own lesson plans. I’m experiencing some anxiety about this since we start next Wednesday with the first family session of the Moving Traditions curriculum. This approach to the student preparing for their Bar or Bat Mitzvah will, apparently, be controversial because it doesn’t focus on the ritual of the morning service, but on the students’ social, emotional, and developmental needs. Alan, Jamie, and Tara will deal with that. Not me.

Kate’s had several days in a row with no nausea. Yeah! That means she feels better and can get some things done. In doing so, however, the extent of her loss of stamina, weight loss and Sjogren’s Syndrome, has become apparent. She still needs to rest frequently. If she can modulate the nausea, either through careful eating or an eventual diagnosis or using medical marijuana, the next step is to get some weight gain, some stamina improvement. If possible. Or, we may have to adjust to a new normal.

Kate’s had several days in a row with no nausea. Yeah! That means she feels better and can get some things done. In doing so, however, the extent of her loss of stamina, weight loss and Sjogren’s Syndrome, has become apparent. She still needs to rest frequently. If she can modulate the nausea, either through careful eating or an eventual diagnosis or using medical marijuana, the next step is to get some weight gain, some stamina improvement. If possible. Or, we may have to adjust to a new normal.

I’ve been absorbed in lesson planning, training for the school year, climbing my steep learning curve about matters Jewish and matters middle school. That’s my way. Dive into something new, leave most other things behind until I’ve gotten where I feel like I need to be. Not there yet, though I imagine after a few class sessions, I will be. Sort of a head down, blinkers on time. My writing has dwindled and so have submissions.

Over the last couple of weeks, while I work out, I’ve been watching a Teaching Company course on the aging brain. I recommend it. Highly. It’s helped me understand why this approach, head down blinkers on, is developmentally appropriate for me. For example, the aging brain, on average, loses some processing speed, executive functions, and crispness of episodic memory (memory tied to a person or place and seen from a first person perspective.) over each decade, beginning in the twenties.

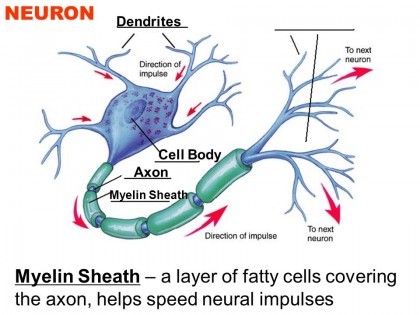

The underlying issue seems to be gradual demyelination of the axons which constitute the white matter in our brain. With myelin sheathing over their length axons can carry information very fast, without it somewhere around 2 meters per second, or human walking speed. As our processing speed declines, so do brain functions like the executive management of brain activity by the prefrontal cortex. It’s this one, the decline in executive function, that requires the head down, blinkers on approach to new activity or to tasks we need to complete. As we age, we no longer handle distractions as well, getting pulled away from this to focus on the shiny that.

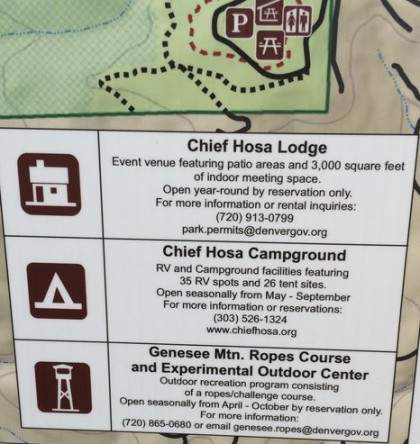

I like knowing this because it helps me understand my daily third phase life better. The thinking process itself is not impaired, just the speed and our ability to stay with a task. It helped explain a very uncomfortable moment for me at the Genesee Ropes Course on Sunday. Jamie and I were with the 6th and 7th graders. Adrienne, a ropes course employee had just explained the rules of a warmup game. One of the rules was that we had we could not throw a soft toy to someone who’d already gotten one on that round.

I got the stuffed unicorn on the third or fourth toss. When I tossed it to Alex, Adrienne asked, “Did he break a rule?” All the kids and Jamie nodded. Yes, he had. Why? Alex had already gotten the unicorn. Oh, shit. This was the first interaction between me and these kids as a group and I looked like a doofus. I didn’t remember the rule at all. There were plenty of things to distract me. The continental divide in the distance. A wind blowing through the trees. Trying to concentrate on learning kid’s names. General anxiety about not knowing the kids at all. Whatever it was, my executive function let me go, Oh, fish on bicycle, instead of hearing, no throwing to someone who’s already received it.

I got the stuffed unicorn on the third or fourth toss. When I tossed it to Alex, Adrienne asked, “Did he break a rule?” All the kids and Jamie nodded. Yes, he had. Why? Alex had already gotten the unicorn. Oh, shit. This was the first interaction between me and these kids as a group and I looked like a doofus. I didn’t remember the rule at all. There were plenty of things to distract me. The continental divide in the distance. A wind blowing through the trees. Trying to concentrate on learning kid’s names. General anxiety about not knowing the kids at all. Whatever it was, my executive function let me go, Oh, fish on bicycle, instead of hearing, no throwing to someone who’s already received it.

It still looks the same to the outsider. I missed the rule, and as a result, screwed up in its execution. But now I understand that this is not a sign of dementia or other deep seating problem, but rather a normal, though irritating, side effect of demyelination.

When we were at the Beth Evergreen teachers’ workshop last week, Tara asked us what we thought we brought to the classroom. “I bring a spirit of inquiry, of curiosity,” I said, then surprised myself by voicing an insight I didn’t realize I’d had, “I’ve always lived the questions, not the answers.” True that.

When we were at the Beth Evergreen teachers’ workshop last week, Tara asked us what we thought we brought to the classroom. “I bring a spirit of inquiry, of curiosity,” I said, then surprised myself by voicing an insight I didn’t realize I’d had, “I’ve always lived the questions, not the answers.” True that.

Discovering an odd phenomenon. My feelings bubble up with less filtering. I don’t feel depressed, not labile. Not really sure how to explain this, though it may be a third phase change? Or, maybe just me, for some reason.

Discovering an odd phenomenon. My feelings bubble up with less filtering. I don’t feel depressed, not labile. Not really sure how to explain this, though it may be a third phase change? Or, maybe just me, for some reason. In fact, there’s another example. Over the last few months I’ve been using the word sweet a lot. Our dogs are sweet. Ruth. The folks at Beth Evergreen. Minnesota friends. The loft. My life. I seem to see sweetness more now. I haven’t lost my political edge, my anger at injustice or a willingness to act, but the world has much, much more nuance now at an emotional level.

In fact, there’s another example. Over the last few months I’ve been using the word sweet a lot. Our dogs are sweet. Ruth. The folks at Beth Evergreen. Minnesota friends. The loft. My life. I seem to see sweetness more now. I haven’t lost my political edge, my anger at injustice or a willingness to act, but the world has much, much more nuance now at an emotional level.

I see my own holy soul, now claiming more space, taking back some of the aspects of my life I had given over to achievement, to striving. This is strange because it comes as I’ve begun to reach for achievements I’ve blocked for decades. The work of submitting my writing feels both unimportant and necessary. I’m immersed in a community, Beth Evergreen, which encourages the growth and expansion of my holy soul. This is true religion, with the small r, the connecting and reconnecting of our inner life with the great vastness, our part in it highlighted, made clear at the same time as our limitedness.

I see my own holy soul, now claiming more space, taking back some of the aspects of my life I had given over to achievement, to striving. This is strange because it comes as I’ve begun to reach for achievements I’ve blocked for decades. The work of submitting my writing feels both unimportant and necessary. I’m immersed in a community, Beth Evergreen, which encourages the growth and expansion of my holy soul. This is true religion, with the small r, the connecting and reconnecting of our inner life with the great vastness, our part in it highlighted, made clear at the same time as our limitedness.

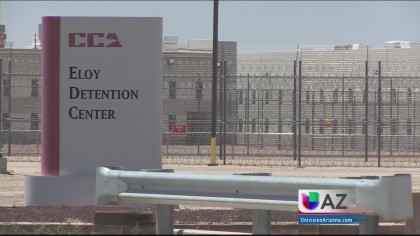

Sad. Mad. Incredulous. Shocked. Mystified. Hurt.

Sad. Mad. Incredulous. Shocked. Mystified. Hurt.  Ms. Montoya became too emotional to talk. Several times. She answered question after question from this audience of maybe 75 people, all outraged, most wanting to do something. Kate stood up and asked what kind of medical care did these children receive? Ms. Montoya said no particular medical care was available. That means diabetes goes untreated. Other chronic conditions, too. Another asked what kind of education the kids were getting? Ms. Montoya said, “The kids speak Spanish; all the guards and caretakers speak English.”

Ms. Montoya became too emotional to talk. Several times. She answered question after question from this audience of maybe 75 people, all outraged, most wanting to do something. Kate stood up and asked what kind of medical care did these children receive? Ms. Montoya said no particular medical care was available. That means diabetes goes untreated. Other chronic conditions, too. Another asked what kind of education the kids were getting? Ms. Montoya said, “The kids speak Spanish; all the guards and caretakers speak English.”

Part of the problem for legal projects like Florence and

Part of the problem for legal projects like Florence and  *Valentina Restrepo Montoya was born in Boston to Colombian-immigrant parents. She earned her J.D. from Berkeley Law, where she advocated on behalf of asylum seekers, latinx workers, latinx tenants, and indigent defendants in criminal cases. Valentina clerked for The Southern Center for Human Rights, where she investigated language access to adult and juvenile courts. After law school, she joined The Southern Poverty Law Center, dedicating herself to litigation against The Alabama Department of Corrections for providing constitutionally inadequate medical and mental health care to prisoners, and not complying with The Americans with Disabilities Act. Prior to joining The Florence Project, Valentina was an assistant public defender in Birmingham, Alabama. She enjoys playing soccer, reading The New Yorker, practicing intersectional feminism, and rooting for The New England Patriots.

*Valentina Restrepo Montoya was born in Boston to Colombian-immigrant parents. She earned her J.D. from Berkeley Law, where she advocated on behalf of asylum seekers, latinx workers, latinx tenants, and indigent defendants in criminal cases. Valentina clerked for The Southern Center for Human Rights, where she investigated language access to adult and juvenile courts. After law school, she joined The Southern Poverty Law Center, dedicating herself to litigation against The Alabama Department of Corrections for providing constitutionally inadequate medical and mental health care to prisoners, and not complying with The Americans with Disabilities Act. Prior to joining The Florence Project, Valentina was an assistant public defender in Birmingham, Alabama. She enjoys playing soccer, reading The New Yorker, practicing intersectional feminism, and rooting for The New England Patriots.

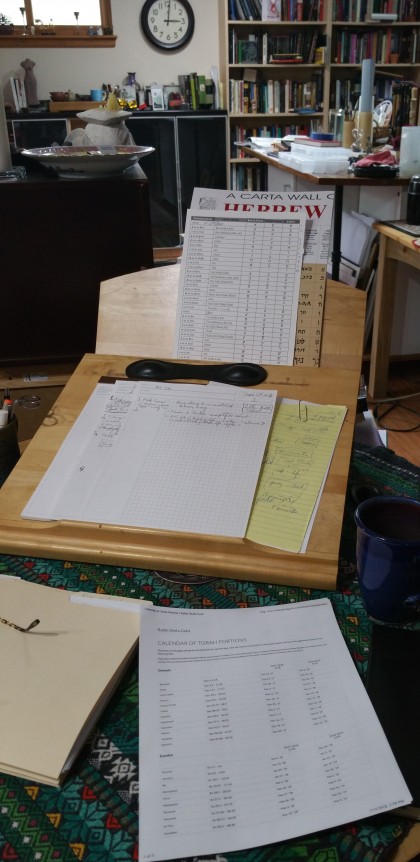

With these elements identified lesson planning will be easier because content can be plucked from any of the columns to enhance a particular class. There’s another move in the process, integrating the b’nai mitzvah curriculum developed by a national organization called Moving Traditions with those classes for which Alan and I have to develop our own lesson plans. Once how we do that is decided and dates for the b’nai mitzvah classes show up on the calendar, we should be able to move fairly quickly to a plan for the year.

With these elements identified lesson planning will be easier because content can be plucked from any of the columns to enhance a particular class. There’s another move in the process, integrating the b’nai mitzvah curriculum developed by a national organization called Moving Traditions with those classes for which Alan and I have to develop our own lesson plans. Once how we do that is decided and dates for the b’nai mitzvah classes show up on the calendar, we should be able to move fairly quickly to a plan for the year.

Why are we so reluctant to recognize that racism, sexism, homelessness, income inequality, white fear are the result of decisions we’ve made collectively and individually? I think the answer lies in ideas Arthur Brooks identifies as the bedrocks of conservative thought. Below is a portion of that article,

Why are we so reluctant to recognize that racism, sexism, homelessness, income inequality, white fear are the result of decisions we’ve made collectively and individually? I think the answer lies in ideas Arthur Brooks identifies as the bedrocks of conservative thought. Below is a portion of that article,  But, to sacralize that unique reality, “…conservatives have always placed tremendous emphasis on the sacred space where individuals are formed.” says Brooks, serves to deny its perniciousness, its damning of so many to lives of desperation, marginalized from both economic and cultural blessings. Once we emerge in the era, the family, the town or neighborhood or rural place, the religious or areligious space gifted to us, the nation of our birth, once we are over being thrown into circumstances beyond our volition, we gain the power of choice.

But, to sacralize that unique reality, “…conservatives have always placed tremendous emphasis on the sacred space where individuals are formed.” says Brooks, serves to deny its perniciousness, its damning of so many to lives of desperation, marginalized from both economic and cultural blessings. Once we emerge in the era, the family, the town or neighborhood or rural place, the religious or areligious space gifted to us, the nation of our birth, once we are over being thrown into circumstances beyond our volition, we gain the power of choice.

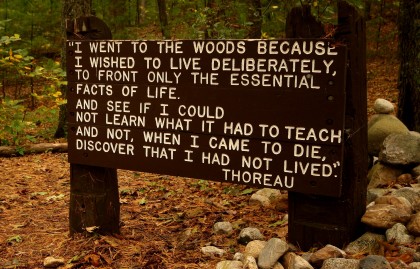

But, and I might call this the Emersonian turn, we cannot use the offerings of the past without remembering his introduction to Nature: “The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs?”

But, and I might call this the Emersonian turn, we cannot use the offerings of the past without remembering his introduction to Nature: “The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs?”