Winter Moon of the Long Nights

Last night, third night in a row at Beth Evergreen, was the MVP, the mussar vaad practice group. Tuesday was the unveiling of the third stained glass window. Wednesday was the first class of the third in the first year kabbalah curriculum, the Mystical Hebrew Letters. On a personal, physical level this many evening sessions, which extend well beyond my usual 8 p.m. bedtime and then require a half hour ride home afterward, exhaust me. But on a psycho-spiritual level the nourishment I receive more than compensates.

As I wrote this last sentence, I looked up at Black Mountain and noticed a pink glow, a penumbra at its peak. A good symbol for the new understanding that is beginning to dawn on me.

In the mid-day mussar class, where we are near the end of the Messilat Yesharim, the path of the upright, by the 18th century kabbalist, Rabbi Moshe Luzzato, Jamie commented, “Remember, these are kabbalists. They include proof texts as an invitation to rethink them as metaphor, not to accept their literal meaning.” Jamie has said this before, in the kabbalist classes especially. “The Torah is a metaphor, not history.”

A bit later, he asked, “What is Torah study?” This was a topic we covered over a year ago when beginning Luzzato’s work. Torah study is not about content. It is not, in other words, limited to scholarship about Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Torah study is a method and it involves paying close attention to the person next to you, to the sunrise over Black Mountain, to the cry of a sparrow, to the way a lodgepole pine sloughs off snow, to the needs of the dog sleeping beside your chair. to the nature of fire crackling in the fireplace. Torah study is about loving attentiveness. It is a way of engaging the sacred world which we can know first from within our own person and which permeates that which we encounter throughout our lives.

And, again, aha! The sun, the sacred sun with its life-giving light, just lit up Black Mountain and showed me a sign, a way of illustrating a literally dawning awareness. The wind, the finger of the sacred blows as the ruach, the breath of spirit, the breath of life and moves the lodgepole pines in our front yard. The pines themselves erupt out of the stony Shadow Mountain ground, able to express life in a soil mostly barren of the rich nutrients available in the farmlands of the American Midwest.

I find this means I can read the word God in a new way. Shortly after Jamie commented on Torah study, we read a sentence in Messilat Yesharim that included the English word omnipresence, as in God’s omnipresence. I asked Jamie what Hebrew lay behind this translation. He looked it up, “Hmm. Something like, permeated knowledge.”

God lit up for me. Ah, if I do Torah study, if I engage in loving attentiveness to my Self, my own Soul, and those of others and of the broader natural world, then I can find the knowledge which permeates all things, that very same shards of the sacred that shattered just after the tzimtzum to create our universe. That is God being available everywhere. This is far different from the Latinate imponderable of omnipresence, sort of an elf on the shelf deity lurking in every spot, finding you everywhere. And judging.

No. God is another word for the intimate linkage between and among all things, from the smallest gluon to the largest star. God is neither a superparent nor a cosmic Santa Claus writing down your behaviors in the book of deeds; God is a metaphor for the sacred knowledge which permeates the perceivable, and the unperceivable, world.

No. God is another word for the intimate linkage between and among all things, from the smallest gluon to the largest star. God is neither a superparent nor a cosmic Santa Claus writing down your behaviors in the book of deeds; God is a metaphor for the sacred knowledge which permeates the perceivable, and the unperceivable, world.

Our deeds are, of course, written in the very real book of our life, so they have consequences, not only on our life as whole, but as they impact others and that same world which we all inhabit. You could also see God’s judgment as the manifestation of those consequences, in their positive and negative natures, not as a divine finger shaking or outright punishing, but as ripples from one instance of the sacred to the another.

The solstices mark swings to and from extremes, from the longest day to the longest night, there, and as with Bilbo, back again. Darkness and light are never steady in their presence. The earth always shifts in relation to the sun, gradually lengthening the days, then the nights.

The solstices mark swings to and from extremes, from the longest day to the longest night, there, and as with Bilbo, back again. Darkness and light are never steady in their presence. The earth always shifts in relation to the sun, gradually lengthening the days, then the nights. In these long nights the cold often brings clear, cloudless skies. The wonderful Van Gogh quote that I posted a few days ago underscores a virtue of darkness, one we can experience waking or asleep. Dreaming takes us out of the rigors of day to day life and puts us in the realm where ideas and hopes gather. So, the lengthening of the nights increases our opportunity to experience dream time. Whether you believe in Jung’s collective unconscious or not-I do, the rich resources of dreaming are available to us with greater ease when the nights are long and the cold makes sleeping a joy.

In these long nights the cold often brings clear, cloudless skies. The wonderful Van Gogh quote that I posted a few days ago underscores a virtue of darkness, one we can experience waking or asleep. Dreaming takes us out of the rigors of day to day life and puts us in the realm where ideas and hopes gather. So, the lengthening of the nights increases our opportunity to experience dream time. Whether you believe in Jung’s collective unconscious or not-I do, the rich resources of dreaming are available to us with greater ease when the nights are long and the cold makes sleeping a joy.

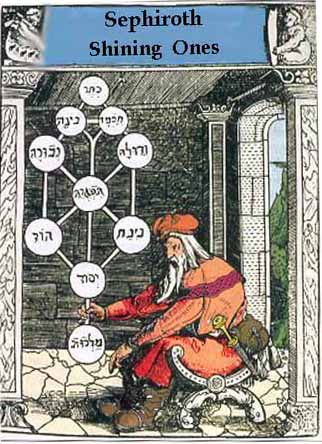

CC’s work with Maslow sparked a conversation about the difference between human agency in moving up the pyramid as opposed to the necessity of God’s agency. Within my worldview this is a false dichotomy, but the conversation was fruitful. It’s a false dichotomy to me for two reasons. 1. How else would God move someone up the pyramid save through human agency? 2. Since I see energy moving up and down the tree of life, from the invisible to the visible and back through the visible to the invisible, this energy flow is the key agency involved, imh. I might call it chi, or prana, or l’chaim. Could also call it divine or vitality or consciousness. I don’t see that adding God to the conversation accomplishes much.

CC’s work with Maslow sparked a conversation about the difference between human agency in moving up the pyramid as opposed to the necessity of God’s agency. Within my worldview this is a false dichotomy, but the conversation was fruitful. It’s a false dichotomy to me for two reasons. 1. How else would God move someone up the pyramid save through human agency? 2. Since I see energy moving up and down the tree of life, from the invisible to the visible and back through the visible to the invisible, this energy flow is the key agency involved, imh. I might call it chi, or prana, or l’chaim. Could also call it divine or vitality or consciousness. I don’t see that adding God to the conversation accomplishes much. In the end I felt heard and honored for my understanding of the relationship between the cyclical turn of the seasons and the meaning of the tree of the life to kabbalists.

In the end I felt heard and honored for my understanding of the relationship between the cyclical turn of the seasons and the meaning of the tree of the life to kabbalists. Since I have long believed that the world’s religions are philosophy and poetry accessible to all, I remain eager to learn from them. Since I know their claims cannot all be true, I choose to remain outside them, yet to walk with them as part of my journey. During college, when fellow students were turning to Asian faiths: the hare krishnas, zen, tibetan mysticism, I believed that the religious traditions of the West were most culturally attuned to the American mind. I still believe that and find Judaism and its traditions and thoughts, like Christianity, trigger a depth of understanding I don’t get from the Asian faiths.

Since I have long believed that the world’s religions are philosophy and poetry accessible to all, I remain eager to learn from them. Since I know their claims cannot all be true, I choose to remain outside them, yet to walk with them as part of my journey. During college, when fellow students were turning to Asian faiths: the hare krishnas, zen, tibetan mysticism, I believed that the religious traditions of the West were most culturally attuned to the American mind. I still believe that and find Judaism and its traditions and thoughts, like Christianity, trigger a depth of understanding I don’t get from the Asian faiths. Think I’ve figured out my kabbalah presentation. Still a bit rough around the edges but that’s going to be part of it. It’ll be a how to think with the tree of the life as a touchstone example, using the Great Wheel as an instance.

Think I’ve figured out my kabbalah presentation. Still a bit rough around the edges but that’s going to be part of it. It’ll be a how to think with the tree of the life as a touchstone example, using the Great Wheel as an instance. This a crucial difference between a secular, scientific world view and a mystical one. Entropy posits, as I mentioned in a post not long ago, that all things die, including death, I suppose. The Great Wheel and the tree of life challenge that grim metaphysics with an alternative.

This a crucial difference between a secular, scientific world view and a mystical one. Entropy posits, as I mentioned in a post not long ago, that all things die, including death, I suppose. The Great Wheel and the tree of life challenge that grim metaphysics with an alternative. God became fractionated during the tzimtzum, the contraction of divine energy that made the finite possible. This idea is still difficult for me, but I’m just accepting it for the purposes of this presentation. During the tzimtzum the infinite light, ohr, tried to manifest in the finite, filling the space created by the contraction, but the vessel, things, (ein sof = no-things, infinity) could not hold it and shattered. That shattering created all the elements that now make up our universe. (and other universes, too) Trapped inside all of these elements is the ohr. The ascent and descent of divine energy, from the keter to malchut and backup through the sephirot to the keter from malchut, is the way the ohr will once again join with the infinite. How? No clue.

God became fractionated during the tzimtzum, the contraction of divine energy that made the finite possible. This idea is still difficult for me, but I’m just accepting it for the purposes of this presentation. During the tzimtzum the infinite light, ohr, tried to manifest in the finite, filling the space created by the contraction, but the vessel, things, (ein sof = no-things, infinity) could not hold it and shattered. That shattering created all the elements that now make up our universe. (and other universes, too) Trapped inside all of these elements is the ohr. The ascent and descent of divine energy, from the keter to malchut and backup through the sephirot to the keter from malchut, is the way the ohr will once again join with the infinite. How? No clue. This is a malchutian manifestation, I think, of the ascent and descent and ascent again of divine energy represented by the tree of life. Why? Well, until the divine energy passes through yesod and becomes real in malchut, it is hidden, invisible, just like the vivifying function of the soil and the air and the sun is hidden during the fallow time. Both represent the cyclical nature of things coming into existence from apparent no-thing, then returning themselves to the invisible, the hidden.

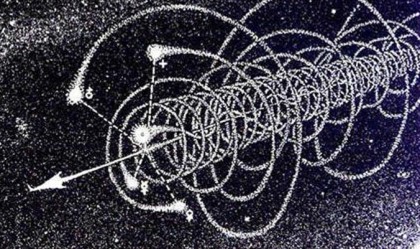

This is a malchutian manifestation, I think, of the ascent and descent and ascent again of divine energy represented by the tree of life. Why? Well, until the divine energy passes through yesod and becomes real in malchut, it is hidden, invisible, just like the vivifying function of the soil and the air and the sun is hidden during the fallow time. Both represent the cyclical nature of things coming into existence from apparent no-thing, then returning themselves to the invisible, the hidden. The slinkys I will hand out, tiny one-inch ones, illustrate what I mean. The Great Wheel turns through one year, one orbit around the sun, then repeats and is, in that, cyclical and not chronological. But, if you link this orbit to that one we get a spiral as our rapidly moving planet follows our solar system around the galaxy at unimaginable rates of speed. The Great Wheel then extends in space, in a spiral, this year’s revolution becoming another while the whole planet and its sun captive neighbors push further and further around the Milky Way. And, just to add complexity, as the whole galaxy moves, too.

The slinkys I will hand out, tiny one-inch ones, illustrate what I mean. The Great Wheel turns through one year, one orbit around the sun, then repeats and is, in that, cyclical and not chronological. But, if you link this orbit to that one we get a spiral as our rapidly moving planet follows our solar system around the galaxy at unimaginable rates of speed. The Great Wheel then extends in space, in a spiral, this year’s revolution becoming another while the whole planet and its sun captive neighbors push further and further around the Milky Way. And, just to add complexity, as the whole galaxy moves, too. Just noticed a quirky reminder of Coco and the song that saves Hector, Remember Me. Each time I have to login into a site, I enter a username and a password. Then, just below the blanks for those is a small square to check or not. It says, remember me? It reminds me, too, of the posts of the dead on Facebook. I can’t think of anyone else right now, though I know there are others, but I still get the occasional reminder for Kathleen Donahue who died two years ago from lung cancer. In my instance there is the now quite long trail of bytes and bits that breadcrumb my life over the last decade plus. Perhaps we could create

Just noticed a quirky reminder of Coco and the song that saves Hector, Remember Me. Each time I have to login into a site, I enter a username and a password. Then, just below the blanks for those is a small square to check or not. It says, remember me? It reminds me, too, of the posts of the dead on Facebook. I can’t think of anyone else right now, though I know there are others, but I still get the occasional reminder for Kathleen Donahue who died two years ago from lung cancer. In my instance there is the now quite long trail of bytes and bits that breadcrumb my life over the last decade plus. Perhaps we could create

I really like cooking, used to do a lot more. It requires mindfulness and produces a meal for others to enjoy. Just popping up from my days of anthropology:

I really like cooking, used to do a lot more. It requires mindfulness and produces a meal for others to enjoy. Just popping up from my days of anthropology:  We’re not like dogs in that fundamental sense. As Emerson observed, “The days are gods.” Another binary opposition is the sacred and the profane, like the holy and the secular, ordinary time and sacred time. We imbue, out of our speculative capacity, the passing of time with certain significance. The day we were born. The yahrzeit notion in Judaism, celebrating the anniversary of a death. A day to celebrate the birth of a god, or to remember a long ago war against colonial masters. We identify certain days, a vast and vastly different number of them, as new year’s day, the beginning of another cycle marked by the return of our planet to a remembered spot on its journey.

We’re not like dogs in that fundamental sense. As Emerson observed, “The days are gods.” Another binary opposition is the sacred and the profane, like the holy and the secular, ordinary time and sacred time. We imbue, out of our speculative capacity, the passing of time with certain significance. The day we were born. The yahrzeit notion in Judaism, celebrating the anniversary of a death. A day to celebrate the birth of a god, or to remember a long ago war against colonial masters. We identify certain days, a vast and vastly different number of them, as new year’s day, the beginning of another cycle marked by the return of our planet to a remembered spot on its journey. When we merge our speculative fantasies with the chemistry of changing raw food into a beautiful cooked meal, we can have extraordinary times. The natural poetics of wonder join the very earthy act of feeding ourselves to create special memories. Very often on those days we gather with our family, a unit that itself memorializes the most basic human purpose of all, procreation of the species. We don’t tend to think of these most elemental components, but they are there and are sine qua non’s of holidays.

When we merge our speculative fantasies with the chemistry of changing raw food into a beautiful cooked meal, we can have extraordinary times. The natural poetics of wonder join the very earthy act of feeding ourselves to create special memories. Very often on those days we gather with our family, a unit that itself memorializes the most basic human purpose of all, procreation of the species. We don’t tend to think of these most elemental components, but they are there and are sine qua non’s of holidays. The tree of life, the tree of immortality guarded by the angel with the flaming sword; the tree itself still growing in paradise, concealed by language, by our senses, by the everydayness of our lives; the path back to the garden often forgotten, the exile from paradise a separation so profound that we no longer know the location of the trail head and even harder, we no longer have a desire to search for it.

The tree of life, the tree of immortality guarded by the angel with the flaming sword; the tree itself still growing in paradise, concealed by language, by our senses, by the everydayness of our lives; the path back to the garden often forgotten, the exile from paradise a separation so profound that we no longer know the location of the trail head and even harder, we no longer have a desire to search for it. But here’s the trap. Metaphor, of course! I studied philosophy, religion, anthropology in college. Then, after a few years stuck in unenlightened instinctual behavior-the storied sex, drugs and rock and roll of the sixties and seventies-I moved to seminary. The trap tightened. I learned about the church, scripture old and new, ethics, church history. It was exhilarating, all this knowledge. I soaked it up. I remained though stuck in the intellectual triad, pushing back and forth between the polarity of intuitive wisdom, hochmah, and analytical thought, binah, often not going on to daat, or understanding. I learned, but did not integrate into my soul.

But here’s the trap. Metaphor, of course! I studied philosophy, religion, anthropology in college. Then, after a few years stuck in unenlightened instinctual behavior-the storied sex, drugs and rock and roll of the sixties and seventies-I moved to seminary. The trap tightened. I learned about the church, scripture old and new, ethics, church history. It was exhilarating, all this knowledge. I soaked it up. I remained though stuck in the intellectual triad, pushing back and forth between the polarity of intuitive wisdom, hochmah, and analytical thought, binah, often not going on to daat, or understanding. I learned, but did not integrate into my soul. My heart knew I had gotten lost, in exile once again. In Dante’s words in Canto 1 of the Divine Comedy:

My heart knew I had gotten lost, in exile once again. In Dante’s words in Canto 1 of the Divine Comedy: At the time of its crumbling another path had begun to open for me. Fiction writing emerged when, ironically, I began writing my Doctor of Ministry thesis. Instead of working on it I ended up with 30,000 plus words of what would become my first novel, Even The Gods Must Die. Irony in the title, too, I suppose.

At the time of its crumbling another path had begun to open for me. Fiction writing emerged when, ironically, I began writing my Doctor of Ministry thesis. Instead of working on it I ended up with 30,000 plus words of what would become my first novel, Even The Gods Must Die. Irony in the title, too, I suppose. Even so, I sat behind the barrier, the flaming sword, the metaphor trap. Beth Evergreen and Rabbi Jamie Arnold have started me on a journey back to where I began, immersed in the dark. Seeking for the light, yes, but happy now in the darkness, too. The Winter Solstice long ago became my favorite holiday of the year.

Even so, I sat behind the barrier, the flaming sword, the metaphor trap. Beth Evergreen and Rabbi Jamie Arnold have started me on a journey back to where I began, immersed in the dark. Seeking for the light, yes, but happy now in the darkness, too. The Winter Solstice long ago became my favorite holiday of the year. But. At Beth Evergreen I have begun to feel my way back into the fourth triad, the mystery I first encountered on the hard wooden pews in Alexandria, the one pulsing behind the metaphors of tenebrae, of crucifixion, of resurrection, and now of Torah, of language, of a “religious” life. I knew it once, in the depth of my naive young boy’s soul. Now, I may find it again, rooted in the old man he’s become.

But. At Beth Evergreen I have begun to feel my way back into the fourth triad, the mystery I first encountered on the hard wooden pews in Alexandria, the one pulsing behind the metaphors of tenebrae, of crucifixion, of resurrection, and now of Torah, of language, of a “religious” life. I knew it once, in the depth of my naive young boy’s soul. Now, I may find it again, rooted in the old man he’s become.

It was a week of this sort of activity, getting ready for the storm, catching up on errands. My exercise, Jennie’s Dead work suffered, but my choice. This week I’m back at all of that, going to On the Move Fitness on Thursday for a new workout.

It was a week of this sort of activity, getting ready for the storm, catching up on errands. My exercise, Jennie’s Dead work suffered, but my choice. This week I’m back at all of that, going to On the Move Fitness on Thursday for a new workout. Behind the wilderness. Everett Fox is a Jewish scholar who did a translation of the Torah into English while preserving the Hebrew syntax. He made some startling word choices, too, such as in this verse: Exodus 3:2 “He (Moshe) led the flock behind the wilderness–and he came to the mountain of God, to Horev.” Behind is such an interesting choice.

Behind the wilderness. Everett Fox is a Jewish scholar who did a translation of the Torah into English while preserving the Hebrew syntax. He made some startling word choices, too, such as in this verse: Exodus 3:2 “He (Moshe) led the flock behind the wilderness–and he came to the mountain of God, to Horev.” Behind is such an interesting choice. Behind the wilderness is the God who is, as Fox translates later in this passage: I-will-be-there howsoever I-will-be-there. It is this God whose messenger Moshe saw in the bush that burned without being consumed. This God’s name, a verbal noun composed of a mashup of past-present-future tenses for the verb to be, does not reveal. It conceals. It means, it does not describe. The messenger in the bush speaks for the vast whorling reality in which past, present and future are one, all experienced in the present and as part of which we are each integral, necessary and non-interchangeable.

Behind the wilderness is the God who is, as Fox translates later in this passage: I-will-be-there howsoever I-will-be-there. It is this God whose messenger Moshe saw in the bush that burned without being consumed. This God’s name, a verbal noun composed of a mashup of past-present-future tenses for the verb to be, does not reveal. It conceals. It means, it does not describe. The messenger in the bush speaks for the vast whorling reality in which past, present and future are one, all experienced in the present and as part of which we are each integral, necessary and non-interchangeable.