Fall Waxing Harvest Moon

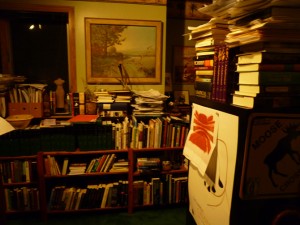

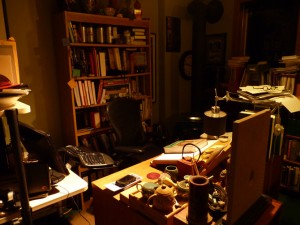

I have begun to accept that I will never read everything I want to read. Books sit stacked up on the floor in my study; they lie on top of rows of other books on bookshelves; all my  bookshelves are full and many have books piled on top of them. Each one I want to read. Some I want to use only as reference, but most I want to read cover to cover. The books range in topic from fairy tales and folklore to basic scientific texts on biology and geology, from philosophy to theology, art history to renaissance life, china, japan, india and cambodia to single dictionaries and the multiple volumes of the OED and the Dictionary of Art. Of course there is fiction, too, and poetry, works on historiography and works on the enlightenment. This doesn’t count the 90 books I now have on my kindle, many fiction, but many non-fiction, too.

bookshelves are full and many have books piled on top of them. Each one I want to read. Some I want to use only as reference, but most I want to read cover to cover. The books range in topic from fairy tales and folklore to basic scientific texts on biology and geology, from philosophy to theology, art history to renaissance life, china, japan, india and cambodia to single dictionaries and the multiple volumes of the OED and the Dictionary of Art. Of course there is fiction, too, and poetry, works on historiography and works on the enlightenment. This doesn’t count the 90 books I now have on my kindle, many fiction, but many non-fiction, too.

When it comes to books and learning, I seem to not have an off button. Maybe it’s a pathology, an escape from the world, from day to day responsibility, could be, but I don’t think so. Reading and learning feel hardwired, expressions of genes as much as personal choice. So it’s tough for me to admit that I have books here, in my own house, that I may never read. A man has only so many hours in a day and I find spending any significant amount of them reading difficult.

That always surprises me. I love to read, yet it often feels like a turn away from the world of politics, the garden, connecting with family and friends, so it takes discipline for me to sit and read for any length of time. Instead, I read in snippets, chunks here and there. Even so, I get a lot read, finishing the Romance of the Three Kingdoms took a lot of dedication, for example. One year, I put the books I finished in one spot after I finished them. I don’t recall the number or the number of pages, but it caused me to sit back and wonder how I’d done it.

Sometimes I fantasize about stopping all other pursuits, sitting down in my chair and begin reading through the most important books, the ones on the top of my list. Right now that would  include the histories of Herodotus and substantial commentary. The Mahabharata. Several works on Asia art. A cabinet full of books on the enlightenment and liberalism. Another cabinet full on calendars and holidays. I will never do it. Why? Because I do have interests, obsessions maybe, that take me out into the garden or over to the State Capitol and the Minnesota Institute of Arts, the homes of the Woolly Mammoths and our children. Kate and I will, I imagine, resume at least some of our SPCO attending when she retires and there will be travel, too.

include the histories of Herodotus and substantial commentary. The Mahabharata. Several works on Asia art. A cabinet full of books on the enlightenment and liberalism. Another cabinet full on calendars and holidays. I will never do it. Why? Because I do have interests, obsessions maybe, that take me out into the garden or over to the State Capitol and the Minnesota Institute of Arts, the homes of the Woolly Mammoths and our children. Kate and I will, I imagine, resume at least some of our SPCO attending when she retires and there will be travel, too.

This relates to an odd self-reflection occasioned by Lou Benders story of my first day on the Ball State Campus. According to him, there was a picture of the Student Body President, I reached out and touched it and told him, “I’m going to do that.” Three years later I ran and lost for Student Body President. The year was 1969. Recalling this, I wondered if my intention, my ability to clarify my direction had waned. Had I defocused, living my life with no clear intentions, drifting along, letting life happen?

Then I recalled the moment I told Kate I wanted to write, the moment four years ago when I realized I had to put my shoulder behind the Great Work, creating a benign human presence on the planet, the moment I began to pester Deb Hegstrom for a spot in the junior docent class of 2005, the time when Kate and I decided to push our property toward permaculture-the harmonious integration of people, plants and animals in a specific spot in a sustainable way. No, I’ve not lost my ability to focus. Not at all.

This life, the one I’m living now, is the one I’ve chosen to live, a life Kate and I have made together. And that feels good.

Who knows, maybe I will finish these books? Who knows?