Samain and the Choice Moon

Monday gratefuls: The Ancient Brothers on gratitude. Snow melted off the Lodgepoles. Great Sol working magic. Black Mountain green again. Seven Stones cemetery. Israel. Becoming a Jew. Sleeping in. Tinned fish. Rice. Cosmic Apples. Holimonth. Advent. Hanukah. Winter Solstice. Christmas. Posada. New Years. Rituals and holidays. Celebrations of deep moments. Christmas lights up along Black Mountain Drive. Gifts, giving and receiving. Those folks who paid for my Thanksgiving meal.

Sparks of Joy and Awe: Rituals and holidays

One brief shining: Books have invaded my house, creeping downstairs from my library a few at a time, insinuating themselves on chairs, coffee tables, anywhere a flat surface offers them purchase, oh and I should say, they also come to the front door in boxes, mailing bags of paper and plastic, insisting on being brought inside out of the cold, warmed up before they get read.

“And when I die / and when I’m gone / there’ll be one child born, in this world / to carry on / to carry on.” And When I Die, Laura Nyro

This song has been ear worm the last couple of days. Blood, Sweat, and Tears is the version I remember. I like the message. And, I believe Max was that child for Kate.

Tomorrow at my beit din, court of judgment, Rabbi Jamie, Joan Greenberg, and Cantor Liz Sacks will convene. Here is Rabbi Jamie’s heads up:

“For the beit din, you will be asked to reflect upon your journey, why you are taking this step at this time, and other open ended questions (to which there are no ‘right’ answers). Your essays have been shared with the other members of the beit din. Let honesty and a playful humility be your guides and you’ll be just fine.”

Here is my “essay:”

How to Become a Pagan and a Jew

Start religious life on a hard wooden pew under a stained-glass window of Jesus praying at Gethsemane. You know, father if you’d just as well, I’d prefer to pass on the whole crucifixion thing. Years and years of sermons, Christmas eve services, Easter services. Enough to create a solid if unremarkable Christian theology. Small town religion in the 1950’s Midwest. What else were you gonna be?

As your brain develops and your education expands, you might find yourself beginning to ask questions. Resurrection? Really. How does that work? Methodist. Nazarene. Missouri Synod Lutheran. Synod? Roman Catholic. Bible Church. So many brands. Why is that? Couldn’t they just agree?

How about that Reverend Steele who ran off to California with the organist?

We haven’t even hit 1965 yet. Maybe in a search for more information you go to the Roman Catholic priest in town and ask for instructions in how to become a Catholic. If he’s smart (yes, he, always he. I mean, Jesus was a guy, right?), and noticing the kind of questions you’ve come with he might introduce you to some proofs for the existence of god.

Like that one where this thing causes that thing and we spend a lot of time going backwards, if this thing caused this then what caused this? Until we reach the universe itself. Bingo! Has to be god, right? Who or what else has the metaphysical moxie to be the cause behind the whole universe. The Prime Mover. Or that other one for example by that guy Anselm: God is that which there is nothing greater than can be conceived. Sort of obvious that one.

Maybe college comes next and you choose to enroll in Philosophy 101. The professor smokes a pipe with tobacco pre-rolled in paper covered plugs. Wears tweed. Quotes whole passages from Plato. In Greek no less. None of those high school teachers held even a small votive candle to this guy.

And he demolishes Anselm and the Prime Mover. Who wants to worship a first cause? I mean, come on. So what if there is something greater than anything else that can be conceived? What does that prove? It’s just an exercise in fuzzy thinking.

Oh. You say. Well. I see. And wander off to Albert Camus who’s much more appealing than Jean-Paul Sartre. Camus later will remind you of Ram Dass who said we’re all just walking each other home. Sorry. A digression there.

After a while the whole Christian story doesn’t add up. Too many contradictions. Too much bloodshed. Too much bigotry. And it gets shoved off to the side while other matters, more immediately germane, take precedent.

Like the Vietnam War. Or feminism. Or Anthropology. Or dope. Or alcohol. Or contract Bridge.

Wait though. Kierkegaard. He was an existentialist, right? Like Camus. Interesting. Well, maybe you decide, I’ll give it a look after all this college stuff finishes up.

Later, say a year or so out of college, drifting from a department store job to selling life insurance to cutting up underwear in a papermill to make rag bond paper, Kierkegaard comes back. Leap of faith, wasn’t it?

Yes. Instead of figuring faith out, act like you have it. See what happens. Before your 7 am shift starts at Fox River Paper, you take to reading the Bible. Writing verses down on notecards and sticking them in your shirt pocket to be read over a baloney sandwich at lunch.

Then this minister. United Church of Christ. Didn’t have that one back home. Turns out he’s opposed to the war, too. That’s a head twister. Not your small-town religion anymore.

You’re really, really bored. Cutting up underwear was not your dream job. OK, maybe you didn’t have a dream job, but that wasn’t it for sure. That wife you married in a rush on that Indian Mound turns out to be sleeping with other guys.

Ooff. You need to get out of this small conservative slice of Wisconsin. Joe McCarthy’s buried in a nearby cemetery.

That minister says. Try seminary. Nah. Why would I do that? Cutting rags no. But minister. Not a chance. Do you even know me? Drugs, sex, and rock and roll. Why not? If you don’t like it, quit. But at least you’ll be somewhere else.

Well, maybe. The application comes in the mail. They offer you housing and food and tuition for the first year. Huh. That wife gets the Volkswagen van. You sell the house, make a little bit. You get some cash and off you go to Minnesota.

Five years later you’re working as a Presbyterian minister. Building affordable housing. Supporting labor unions and immigrants in search of green cards. Challenging standard philanthropy practices. Taking food out to Wounded Knee. Organizing the unemployed to create new jobs, legislation.

Not bad. Making money, hardly anything, but doing things you find important, worthwhile. Significant, in a small way.

Decide to get an advanced degree. A Doctorate. While writing your thesis discover you’ve written one hundred and twenty pages of a novel instead. Even the Gods Must Die. Oh. A clue there.

Your spiritual director, a fussy little guy, but insightful says during one session, “You’re a Druid!” You’ve been reading Celtic mythology, remembering that professor with the pipe. Slipping away from the fold.

One morning you wake up and realize you really don’t buy it anymore. Probably hadn’t bought it for a while. The political work was too good, too solid, too in synch with your heart. You stuffed the doubts and the fact that you represented this religion.

Skip forward a few years. A new wife. Flower gardens. Vegetable gardens. An orchard. Bees. A woods. Wolfhounds and whippets. No longer a minister.

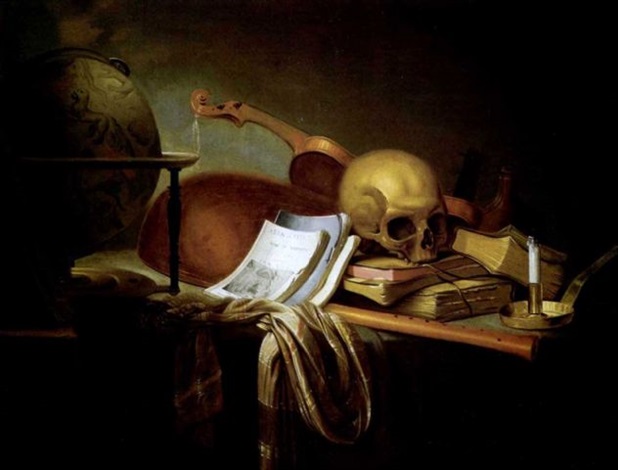

Thinking about a tactile spirituality. A spirituality that goes in and down rather than up and out. You realize the life you nurture in the gardens, the dogs, your small family. That’s real. No fancy philosophy required. Right here. Hands in the soil digging up carrots and beets and onions. Life. Its cycle.

The seasons. The Great Wheel of the Seasons. Putting away apocalyptic linear time for good. Everything has its season. Yes. Everything.

The bees. Are you more important than they are? Is Celt, that 180 pound goofy, loving dog less significant than you? Oh.

Life begins to look less complicated.

Later, much later, that wife dies. And that’s part of the Great cycle. Maybe you get cancer and find solace in the Mountains of your new home. How short your life is compared to theirs.

You begin to live with the seasons, with life as it comes. Not pushing against it, not privileging that life over that. Extending your understanding of life to include the Mountain on which you live. And the ones which surround it.

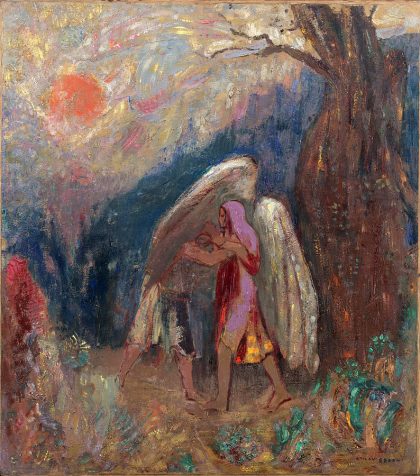

You find your wild neighbors communicating to you. Welcoming you, including you.

That’s how.

Jewish Coda

King David. That’s why. My wife, Kate Olson, a convert at 30, and I searched the Canyon Courier. New to the mountains in 2014. Oh, an education session on King David at Congregation Beth Evergreen.

Folks we met that snowy, bitter cold night came to Kate’s shiva in 2021. Tara, Marilyn. Many others, too, whom we met later.

Kate sat on the board, dressed like a jester for Purim. We attended services, holidays, education events. Got to know people. Studied mussar and kabbalah with Rabbi Jamie.

Made friends. Brought food. Carried tables. You know. The work of community.

Assimilation. Happens so slow. So many Seders, Simchat Torahs. Love that holiday! The dancing and the simcha. Meals in the sukkah. Learning late at night on Shavuot. Breakfasts and lunches with friends from the synagogue.

Teaching in the Hebrew School with my buddy Alan. 6th and 7th graders. Doing the occasional bagel table lesson. Discovering Avivah Zornberg, my favorite.

Two and a half years after Kate’s death. Still a member, still hanging with my friends from the synagogue.

Rabbi Jamie’s lesson on the Mah Tovu. This summer. It hit me. The truth of this Mordecai Kaplan commentary on p. 141 of the Prayerbook: It is only a true and close community that develops associations, traditions and memories that go to make up its soul. To mingle one’s soul with that soul becomes a natural longing.

I had long ago mingled my soul with this sacred community. These people are my people. I am one of them.

The next day I called Jamie. I want to convert. What do I need to do. To bring myself into full alignment with this community.